A new study presented at the American Astronomical Society (AAS 2025) conference reveals new insights into the distant and mysterious objects known as “little red dots.” These objects, initially puzzling to astronomers, have now been identified as massive, short-lived stars, thanks to data gathered by NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). The discovery provides key evidence that could unravel how the universe’s first supermassive black holes formed, offering a critical step forward in our understanding of early cosmic history.

Understanding Little Red Dots: What Are They?

For years, the “little red dots” in deep-space images captured by early telescopes like Hubble remained a mystery. These faint, distant objects appeared as small red spots, but their nature eluded scientists. Initial theories suggested that they could be related to black holes, accretion disks, or even cosmic dust clouds. However, these explanations were complex and did not fully account for the observations.

It was the unprecedented capabilities of the James Webb Space Telescope, launched to capture longer wavelengths of light, that allowed astronomers to explore these objects in greater detail. The new data provided a fresh perspective on these enigmatic dots, revealing their true nature as rapidly growing, massive stars. These stars, some a million times the size of the Sun, are short-lived and composed of primordial hydrogen and helium, devoid of metals.

“Little red dots have been a point of contention since their discovery,” said Devesh Nandal, an astronomer at the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian (CfA) and the lead author of the study available on the arXiv preprint server. “But now, with new modeling, we know what’s lurking in the center of these massive objects, and it’s a single gigantic star in a wispy envelope. And importantly, these findings explain everything that Webb has been seeing.”

A team of astronomers sifted through James Webb Space Telescope data from multiple surveys to compile one of the largest samples of “little red dots” (LRDs) to date. The team started with the Cosmic Evolution Early Release Science (CEERS) survey before widening their scope to…

A team of astronomers sifted through James Webb Space Telescope data from multiple surveys to compile one of the largest samples of “little red dots” (LRDs) to date. The team started with the Cosmic Evolution Early Release Science (CEERS) survey before widening their scope to…

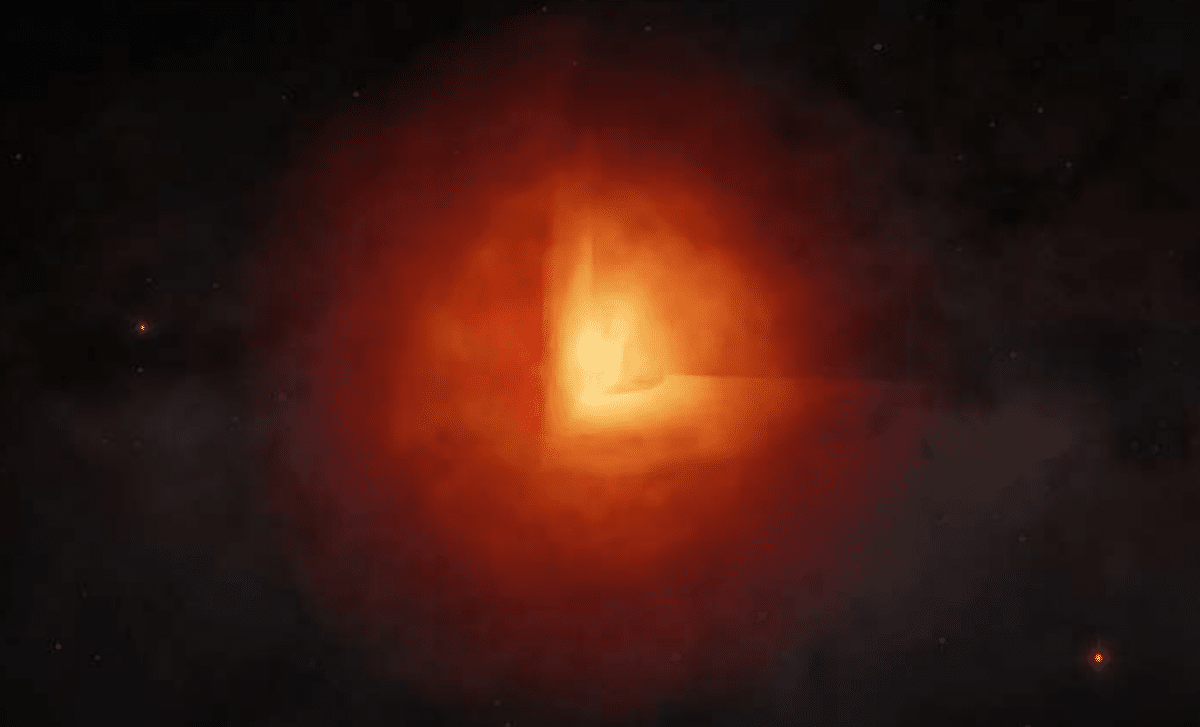

Image: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, Dale Kocevski (Colby College)

The Birth of Supermassive Stars and Black Holes

The new findings shed light on how these massive stars could be the progenitors of supermassive black holes. According to Nandal and his colleagues, these rare stars, free of metals, represent an important phase in the early universe. As these stars grow and burn through their nuclear fuel, they are thought to be the last stage before collapsing into black holes.

“If our interpretation is right, we’re not just guessing that heavy black hole seeds must have existed. Instead, we’re watching some of them be born in real time,” Nandal explained. “That gives us a much stronger handle on how the universe’s supermassive black holes and galaxies grew.”

The study presents a detailed physical model of these stars, suggesting that they possess characteristics that match the red dots seen by Webb. These stars are not only bright but also exhibit a unique V-shaped spectrum, further confirming their status as massive, short-lived stars. This model provides vital clues to how early black holes formed and began to influence the growth of galaxies in the infant universe.

What Makes Webb’s Data So Revolutionary?

The significance of Webb’s data lies in its ability to observe the universe in infrared wavelengths, allowing it to peer deeper into space and observe distant objects that were previously hidden. These “little red dots” represent some of the most ancient and distant objects ever seen, and Webb’s sharp resolution has given scientists unprecedented insight into their true nature.

The fact that these objects have now been confirmed to be massive stars rather than the previously hypothesized black holes or dust clouds marks a major shift in astrophysical theory. This revelation could provide the missing link in understanding how the first supermassive black holes formed in the early universe, which in turn could explain the rapid growth of galaxies.