For the first time in history, astronomers have captured a direct image of black holes locked in orbit around one another — offering the first-ever visual proof that such pairs exist.

Observations gathered by an international network of radio telescopes have revealed two cosmic giants circling each other roughly every 12 years, about 5 billion light-years from Earth. While the discovery is remarkable, scientists stress that more follow-up observations are needed before the finding can be confirmed beyond all doubt.

A pair of cosmic titans

The smaller black hole appears to emit a jet of high-speed particles that twists like a spinning garden hose — or a dog’s wagging tail. The larger one, known as blazar OJ287, is a supermassive behemoth about 18 billion times the mass of our Sun, spewing vast plumes of energy into space.

Lead author Mauri Valtonen, an astronomer at the University of Turku in Finland, explained: “For the first time, we’ve managed to capture an image of two black holes moving toward each other. In the image, they’re identified by the powerful jets of particles they emit. The black holes themselves remain invisible, but their glowing surroundings give them away.”

How black holes grow and shine

Black holes form when massive stars collapse and then grow by devouring gas, dust, stars, and even other black holes. As material spirals inward, friction heats it up, causing it to emit light detectable by telescopes. Such glowing monsters are called active galactic nuclei, or AGN.

At their most extreme, AGN become quasars — colossal black holes billions of times the Sun’s mass, radiating trillions of times brighter than the most brilliant stars. When their energy jets are aimed directly at Earth, we call them blazars.

A long cosmic mystery

Astronomers have already imaged the supermassive black holes at the centers of the Milky Way and Messier 87. But despite long-standing suspicions that OJ287 might contain a pair, telescopes never had the clarity to resolve them separately.

The system’s mysterious flickers were documented as far back as the late 1800s, appearing on old photographic plates before scientists even knew black holes existed. By the 1980s, researchers analyzing those records began to suspect the rhythmic brightening and dimming came from two black holes orbiting each other.

The image that changed everything

To capture the historic picture, astronomers turned to a radio network that included the Russian RadioAstron satellite — a spacecraft that operated between 2011 and 2019 and carried a powerful radio telescope.

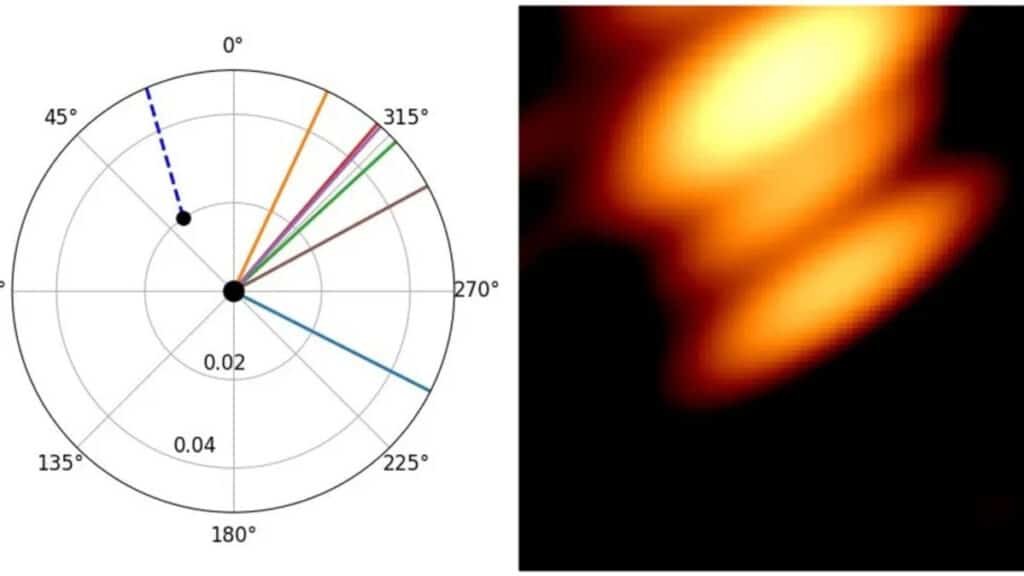

A theoretical diagram (left) showing the location of the black holes and their jets at the time the image was taken, and the radio image (right). (Image credit: Valtonen et al, 2025.)

“The satellite’s antenna reached halfway to the Moon,” Valtonen noted, “dramatically improving our image resolution. In recent years, we’ve relied on ground-based telescopes, which simply can’t match that clarity.”

When they compared the new data to previous calculations, the team pinpointed two distinct jets right where theory predicted each black hole should be. Still, some uncertainty remains: the jets might overlap, meaning astronomers can’t yet rule out the possibility of a single source.

As Valtonen and his team wrote, “When we reach a resolution close to what RadioAstron achieved in the future, we might finally confirm the secondary black hole’s ‘tail-wagging’ motion.”