The Late Ordovician mass extinction (LOME) was a pivotal event that reshaped life on Earth, and a recent study published in Science Advances has uncovered the role this catastrophic event played in the rise of jawed fishes. Roughly 445 million years ago, Earth underwent dramatic climate changes that led to one of the first mass extinction events, wiping out a staggering 85% of marine species. During this time of ecological upheaval, jawed vertebrates, or gnathostomes, emerged as dominant forces in marine ecosystems, setting the stage for the Age of Fishes.

A Global Reset: The Late Ordovician Mass Extinction

The Late Ordovician mass extinction is one of the earliest and most significant extinction events in Earth’s history. Triggered by dramatic climate shifts, marked by the sudden onset of an ice age, this event altered ocean chemistry and led to rapid global cooling, decimating the planet’s marine life. However, as catastrophic as it was, the event also triggered an evolutionary reset, creating ecological opportunities that would allow new species to flourish. This led to the evolution of jawed vertebrates, or gnathostomes, which eventually came to dominate Earth’s oceans.

Professor Lauren Sallan and Ph.D. student Wahei Hagiwara at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology (OIST), and senior author of the study published in Science Advances, explains,

“We have demonstrated that jawed fishes only became dominant because this event happened. And fundamentally, we have nuanced our understanding of evolution by drawing a line between the fossil record, ecology, and biogeography.”

This groundbreaking research sheds new light on how the extinction set the stage for the diversification of jawed fishes, which would go on to become the ancestors of modern sharks, rays, and even the vertebrates we are familiar with today.

The Fossil Record: Tracing the Aftermath of the Extinction

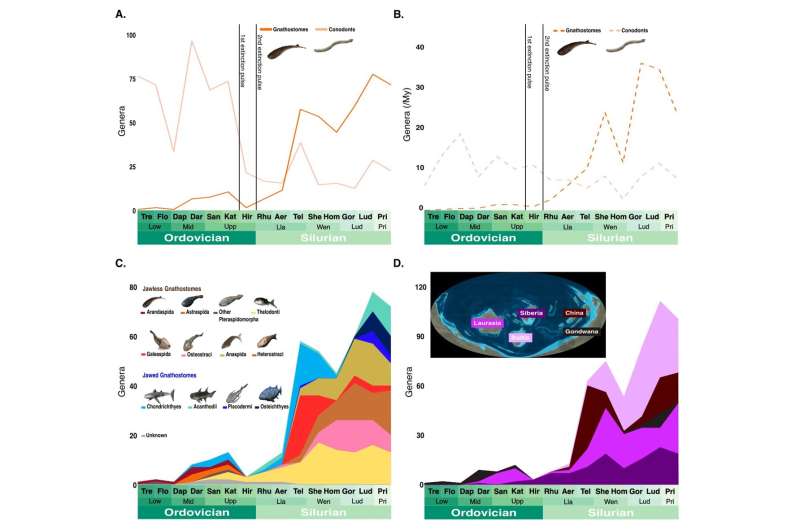

The study’s authors utilized over 200 years of paleontological data from the Late Ordovician and early Silurian periods to build a new database that reveals how ecosystems shifted following the extinction event. By examining fossils, the researchers were able to trace the changes in biodiversity across different regions, offering a unique perspective on how Earth’s ecosystems evolved in the wake of this mass extinction. As Prof. Sallan highlights, “While we don’t know the ultimate causes of LOME, we do know that there was a clear before and after the event. The fossil record shows it.”

This record allowed the research team to identify refugia, isolated ecosystems that survived the harsh conditions of the mass extinction. These refugia became critical in the survival of certain species, providing safe havens where evolutionary changes could unfold. The findings suggest that these refugia played an essential role in the diversification of gnathostomes, the jawed vertebrates that would later dominate marine environments.

The Role of Refugia in Speciation

Refugia, often located in isolated or stable regions, acted as biodiversity hotspots during and after the extinction event. The team’s study found that these areas provided a safe environment for gnathostomes to diversify without the competition from other species that had been wiped out by the mass extinction. As Prof. Sallan explains, “This is the first time that we’ve been able to quantitatively examine the biogeography before and after a mass extinction event. We could trace the movement of species across the globe—and it’s how we’ve been able to identify specific refugia, which we now know played a significant role in the subsequent diversification of all vertebrates.”

In these refugia, gnathostomes could exploit the vacant ecological niches left by extinct species, allowing for rapid diversification. Over millions of years, these early jawed fishes evolved into a variety of species, each occupying different ecological roles. One notable example, as Hagiwara points out, is the discovery of jawed fish fossils in what is now South China. These fossils are closely related to modern sharks and demonstrate how gnathostomes were able to spread from their refugia to new ecosystems once they had developed the ability to travel across open oceans.

The Mystery of Jaw Evolution: New Ecological Niches or Evolutionary Necessity?

The study raises an important question about the evolution of jaws in vertebrates: Did jaws evolve as a way to create new ecological niches, or did they emerge as an adaptation to existing ones? Prof. Sallan suggests that the latter is true, stating, “Our study points to the latter. In being confined to geographically small areas with lots of open slots in the ecosystem left by the dead jawless vertebrates and other animals, gnathostomes could suddenly inhabit a wide range of different niches.”

This insight is crucial for understanding the evolution of jaws in vertebrates. Rather than evolving to exploit new niches, it seems that jaws allowed early gnathostomes to adapt more effectively to the available spaces in the ecosystem that had been left vacant by the extinction of jawless vertebrates and other species. This idea offers a new way to think about the evolutionary process and how species adapt to their environments in response to changing ecological conditions.

The Path Toward the Age of Fishes

The Late Ordovician extinction set the stage for what would eventually become the Age of Fishes. As jawed fishes diversified and adapted to a range of ecological roles, they began to dominate marine ecosystems. Over millions of years, these fishes evolved into the modern sharks, rays, and bony fishes that are the ancestors of today’s marine life. The extinction event, although devastating, was a key factor in shaping the future of life on Earth. As Prof. Sallan summarizes, “This work helps explain why jaws evolved, why jawed vertebrates ultimately prevailed, and why modern marine life traces back to these survivors rather than to earlier forms like conodonts and trilobites.”

By providing a new understanding of how mass extinctions reset ecosystems, the study reveals how pivotal moments in Earth’s history have driven the evolution of life in profound ways. It also demonstrates the resilience and adaptability of species, showing that even in the aftermath of catastrophic events, life finds a way to thrive and evolve in new directions.