Title: Diffuse gamma-ray and neutrino emission from the Milky Way and the local knee in the cosmic ray spectrum

Authors: C. Prévotat, Zh. Zhu, S. Koldobskiy, A. Neronov, D. Semikoz, and M. Ahlers

First Author’s Institution: Sorbonne Université, CNRS, Institut d’Astrophysique de Paris

Access: Published in Phys. Rev. D [closed access]

Cosmic rays are one of the many banes of astronomers’ existences. Though these free protons and nuclei streak through our observations and often mess up our images, we still don’t understand much about where they came from and how they get to be so high-energy. A lot of astronomers try to ignore them (sorry cosmic rays!), but many are very interested in how the ultra-high energy cosmic rays that sometimes hit the Earth’s atmosphere came to be. Are they from supernovae, an active galactic nucleus, or something else entirely?

Researchers are still just beginning to be able to really quantify how high-energy these particles are, and how many of them are there. For instance, are there many more cosmic rays at very high energies than lower energies? Why might this be? Researchers have found that if you plot the amount of cosmic rays we see as a function of their energy (this is the cosmic ray “energy spectrum”), there are some energy zones where there are more cosmic rays, and some zones where there are less. The energy where the relationship starts to change is called a “knee” in the cosmic ray energy spectrum, and astronomers aren’t sure what creates these changes, but know there must be some physical explanation.

Cosmic ray astronomers are also able to investigate cosmic rays through signals from gamma-rays and neutrinos. Cosmic rays that travel to our galaxy will collide with the gas in or near the Milky Way, emitting gamma-rays and neutrinos in these interactions. Researchers are able to observe this emission, and calculate what energies the cosmic rays had to be in order to produce the gamma-ray or neutrino emission.

In today’s paper, researchers compare two different models of cosmic rays to observed emission to explore how these cosmic rays are being produced. They use recent data of the high-energy region of the spectrum (peta-electronvolts!) from the ground-based gamma-ray detector LHAASO to examine their models.

Testing two toy models

The first model they consider is based on a method of grouping cosmic rays into different energy bins and fitting power laws to the energy spectrum. The second model adds a diffusion coefficient to the power laws, which attempts to account for the fact that the cosmic rays will interact with the Milky Way’s magnetic field. They first fit both of their models to the “local” cosmic ray spectrum, i.e. the cosmic rays detected by local instruments on the ground or in the atmosphere. They find that their models well-describe the local cosmic ray spectrum.

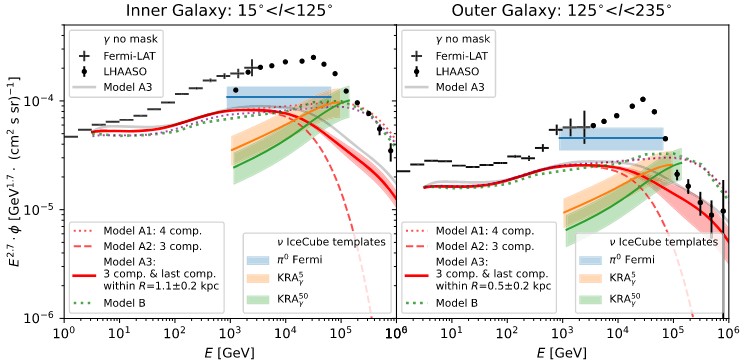

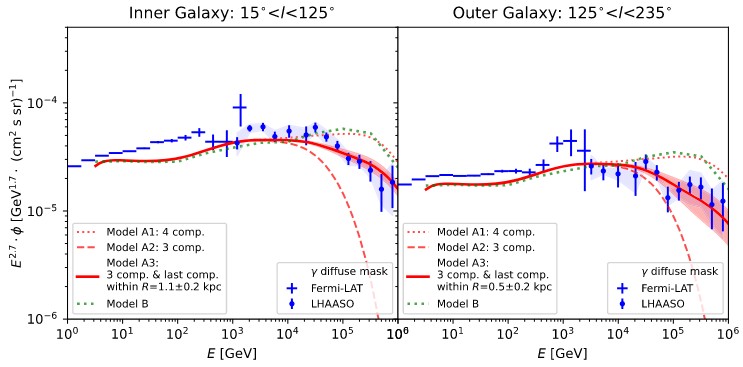

Based on models of how cosmic rays interact with the interstellar medium (ISM), the authors are able to compute what gamma-ray and neutrino emission they expect from these cosmic ray models. They compare this model-produced emission to observations of gamma-rays and neutrinos from Fermi-LAT and LHAASO. They find that their models produce gamma-ray emission similar to the data at energies < 30 TeV, but the predicted neutrino emission is slightly less than the real data, specifically in the inner region of the Milky Way.

Figure 1: Neutrino predictions from Models A (energy bins) and B (diffusion) (both represented as dotted lines), compared to observations from LHAASO and Fermi-LAT (data points). The models can’t fully explain the neutrino emission seen from cosmic ray interactions. Figure 4 in original paper.

Figure 1: Neutrino predictions from Models A (energy bins) and B (diffusion) (both represented as dotted lines), compared to observations from LHAASO and Fermi-LAT (data points). The models can’t fully explain the neutrino emission seen from cosmic ray interactions. Figure 4 in original paper.

Figure 2: Gamma-ray predictions from Models A and B (dotted lines), compared to observations from LHAASO and Fermi-LAT (data points). The models describe the gamma-ray emission well at energies less than 30 TeV, but past then begin to deviate significantly. Figure 3 in original paper.

Figure 2: Gamma-ray predictions from Models A and B (dotted lines), compared to observations from LHAASO and Fermi-LAT (data points). The models describe the gamma-ray emission well at energies less than 30 TeV, but past then begin to deviate significantly. Figure 3 in original paper.

Past 30 TeV, the gamma-ray models (the dashed lines in Figure 2) start to deviate from the data significantly. The authors suggest that this indicates that whatever produces the observed emission is not well-described in their models. They suggest that there may be a “bubble” of very high-energy cosmic rays around the Solar System, potentially from a previous supernova explosion or recent star formation around us.

This study supports the importance of understanding the geometry of the cosmic rays around us, both to test if we are in a local high-energy cosmic ray bubble and more broadly to understand the physical distribution of cosmic rays across the galaxy. Future studies aim to use more data with longer exposure times from the LHAASO to explore this.

Astrobite edited by Anavi Uppal

Feature Image Credit: NASA/DOE/Fermi LAT Collaboration, NRAO/AUI, JPL-Caltech, ROSAT

![]()

I’m a third-year PhD student at Northwestern University. My research explores how we can better understand high-redshift galaxy spectra using observations and modeling. In my free time, I love to read, write, and learn about history.