The fossilized backbones of what appeared to be woolly mammoths have turned out to come from an entirely different and unexpected animal.

Archaeologist Otto Geist came across the bones – two epiphyseal plates from a mammalian spine – on an expedition in 1951 through the Alaskan interior, just north of Fairbanks, in a prehistoric geographic region known as Beringia.

Based on the bones’ appearance and location, Geist’s initial assignment of woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius) made a lot of sense: Late Pleistocene megafauna bones are common in the region, and the sheer size of the backbones is decidedly elephantid.

Geist brought the bones to the University of Alaska’s Museum of the North, where they were archived for more than 70 years.

Thanks to their ‘Adopt-a-Mammoth‘ program, the museum has finally been able to radiocarbon-date the fossils, an undertaking that has raised far more questions than it’s solved.

Related: Dissection of 130,000-Year-Old Baby Mammoth Reveals Glimpse Into Lost World

That’s because these bones, it turns out, are far too young to belong to a woolly mammoth. The carbon isotopes locked within suggest an age of around 2,000 to 3,000 years.

Mammoths, on the other hand, are believed to have gone extinct around 13,000 years ago, bar a few isolated populations that struggled on til about four thousand years ago.

“Mammoth fossils dating to the Late Holocene from interior Alaska would have been an astounding finding: the youngest mammoth fossil ever recorded,” University of Alaska Fairbanks biogeochemist Matthew Wooller and team write in a peer-reviewed paper.

“If accurate, these results would be several thousand years younger than the latest… evidence for mammoth in eastern Beringia.”

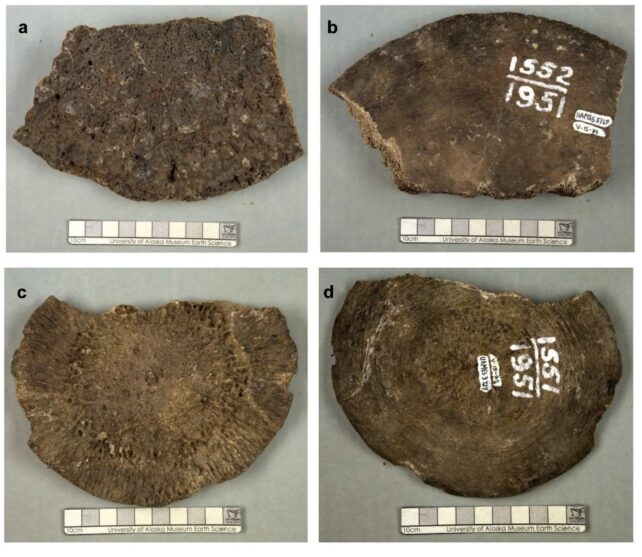

Photographs of the two epiphyseal plates, showing the underside and upper surface of each. (University of Alaska Museum of the North)

Photographs of the two epiphyseal plates, showing the underside and upper surface of each. (University of Alaska Museum of the North)

Before entirely rewriting the timeline of mammoth extinction, the researchers decided they’d better make sure the species had actually been identified correctly. It’s a good thing they did.

“The radiocarbon data and their associated stable isotope data were the first signs that something was amiss,” they write.

The bones contained much higher levels of nitrogen-15 and carbon-13 isotopes than you’d expect for a grass-munching landlubber like the woolly mammoth. Though these isotopes can turn up in land animals, they are far more common in the ocean and so tend to accumulate in the bodies of marine creatures.

No eastern Beringian mammoth has ever been found with such a chemical signal, because the deep Alaskan interior isn’t exactly known for its seafood.

“This was our first indication that the specimens were likely from a marine environment,” Wooller and team explain.

Both mammoth and whale experts agreed it was impossible to identify the specimens based on physical appearance alone: ancient DNA would be essential to “secure the specimens’ true identity.”

Though the specimens were too degraded to contain the kind of DNA stored in our cell nucleus, they were able to extract mitochondrial DNA to compare with that of a Northern Pacific Right whale (Eubalaena japonica) and a Common Minke whale (Balaenoptera acutorostrata).

“Although the mysterious radiocarbon dates of these two specimens have been resolved with the finding that the presumed mammoth fossils were in fact whales, an equally puzzling mystery then came into focus,” Wooller and team point out.

“How did the remains of two whales that are more than 1000 years old come to be found in interior Alaska, more than 400 km (250 miles) from the nearest coastline?”

They came up with a few possible explanations. The first is an “inland whale incursion” through ancient inlets and rivers, which seems very unlikely given the vast size of these whale species and the very small size of Alaska’s inland water bodies (let alone their dearth of appropriate whale food). Though the authors note “wayward cetaceans” are not entirely unheard of.

Perhaps the bones were instead transported from a distant coastline by ancient humans. This has been documented in other regions, but never in interior Alaska.

Lastly, they can’t rule out scientific error. Otto Geist’s collections came from all corners of Alaska, and he donated many specimens to the university during the early 1950s. Could there have been a mix-up at the museum?

It’s a mind-boggling reminder of the physical similarities still shared by our marine mammal kin.

“Ultimately, this may never be completely resolved,” Wooller and team write. “However… this effort has successfully ruled these specimens out as contenders for the last mammoths.”

The research was published in the Journal of Quaternary Science.