In postwar years, doctors in New York reported that a new chemotherapy drug cleared leukemia signs in 15 children for weeks to months.

At the time, most children with acute leukemia died within months, and doctors had few treatments to offer beyond supportive care.

The work to develop a new form of treatment was led by Gertrude B. Elion, a chemist working in the research laboratories of Burroughs Wellcome.

The research drew on clinical collaborations with Sloan Kettering Institute (SKI) and Weill Cornell Medicine (WCM) in New York City.

Elion’s team favored rational drug design, building drugs from known cell chemistry targets, when most companies still relied on trial and error.

In a Nobel essay, Elion said that when she searched for a job after school, labs generally refused to employ women. She took odd jobs, and felt “highly motivated” to search for a cure for cancer.

War-era leukemia treatment

A National Cancer Institute timeline says the Food and Drug Administration approved nitrogen mustard in 1949, after physicians repurposed a chemical warfare agent for cancer treatment.

Doctors had little to offer children with aggressive leukemia, and many families heard that time was short.

Elion and colleagues chased a drug that could slow runaway blood cells without the same blunt damage.

Because cells copy the nucleic acids, DNA and RNA, that carry genetic instructions, Gertrude Elion targeted the chemical steps that build these molecules.

She worked on an antimetabolite, a drug that blocks key cell-building reactions, so fast-growing leukemia cells stalled.

The result was 6-mercaptopurine, often shortened to 6-MP, a purine-like compound that interferes with DNA and RNA production.

Why leukemia grows fast

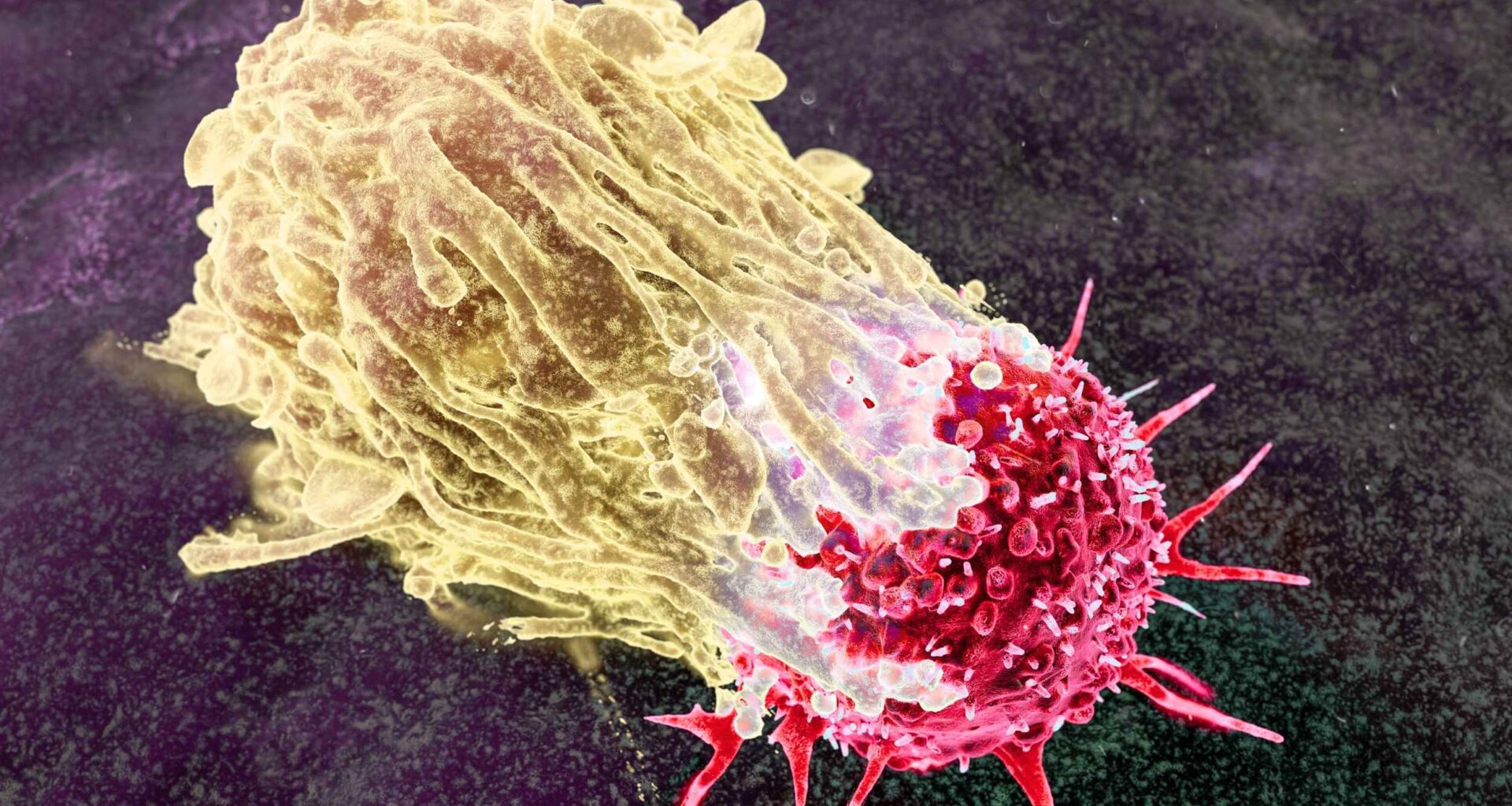

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia, a fast-growing blood cancer common in children, is often called ALL in hospitals.

Bone marrow, soft tissue where blood cells grow, can fill with leukemic blasts that crowd out infection-fighting cells.

These blasts divide quickly, so a drug that interrupts DNA-making can slow them down, at least temporarily.

Tweaking the purines

Purines, chemical “letters” inside DNA and RNA, gave Gertrude B. Elion a starting point for making look-alike molecules.

Her group tested dozens of purine variants in microbes and lab-grown leukemia cells, hunting for a strong blocker.

After animal work suggested tumors could respond, clinicians moved the compound into human testing, despite the grim outlook.

Doctors soon tried 6-MP in children and adults who faced leukemia, hoping the lab results would hold up in patients.

Results were promising enough to keep testing going, yet the team knew the drug alone would not last.

Some early reports described manageable toxicity in many patients, but teams also learned that cancer cells could become resistant.

Leukemia remission implications

Doctors called the improvement remission, indicating that cancer signs fell below detection for a time, even when hidden cells remained.

In blood cancers, remission often means counts look normal and symptoms ease, but treatment usually continues.

With 6-MP, early remission often ended, and researchers watched children relapse after their brief improvement.

Clinicians tracked blood counts closely because chemotherapy can cause myelosuppression, a drop in bone marrow cell output.

When white blood cells fall, infections become more dangerous, so doctors balance dose and timing with constant lab checks.

The same DNA-blocking strategy can also harm the gut and liver, pushing teams to mix drugs carefully.

Combining two attacks

Cancer.gov reports that five-year survival for children with ALL rose from about 60% to roughly 90% after doctors adopted long-term maintenance therapy to prevent relapse.

Maintenance therapy often continues for a long stretch, and many plans use daily 6-MP plus another drug to hold remission.

Because kids take 6-MP at home, families must follow strict schedules and blood tests to keep the drug safe.

By choosing a cell pathway first and then crafting a match, Gertrude B. Elion helped replace guesswork with planned chemistry.

That strategy later guided researchers as they built drugs that target enzymes, receptors, and viral machinery.

It also pushed labs to measure how molecules act inside cells, not just whether they kill cells.

Recognition arrives late

In 1988, the Nobel committee honored Gertrude B. Elion with the prize for principles that improved treatments for leukemia, infections, gout, and transplants.

She started as an organic chemist, but she studied microbiology and pharmacology to understand which molecules might stop diseased cells.

For many women in the 1940s, her path looked unusual, because research labs often hired men in preference.

Childhood leukemia today

Today, clinicians treat ALL in phases, starting with intense therapy and then easing into months of careful follow-up.

Survivors often return to school and sports, yet some carry long-term side effects from drugs that attack dividing cells.

Researchers now test leukemia cells for gene-changes, so they can tailor therapy and avoid unnecessary toxicity.

Lasting treatment effects

Years after treatment ends, doctors still check survivors for late effects that can appear in hormones, bones, or nerves.

Families also watch for anxiety and learning challenges, which can follow long hospital stays and repeated procedures.

Better supportive care and smarter dosing aim to protect quality of life while keeping cure rates high.

Legacy of Gertrude B. Elion

The earliest trials treated children with few options, and researchers accepted risks that would feel different in modern pediatrics.

Ethics boards, consent forms, and data monitors now govern clinical testing, yet families still face hard choices when the cancer returns after a period of improvement.

Even so, the lessons from 6-MP helped shape how cancer drugs move from benches to wards, and then to routine care.

Elion’s drug did not cure leukemia, but it showed that chemistry could extend life and teach new rules.

A woman pushed out of research found a way back in, and children with cancer gained an early chance.

The study is published in Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–