Researchers from McGill University’s Department of Mechanical Engineering and at Drexel University have developed a new method for high-resolution 3D printing using the proboscis of a female mosquito as a biological nozzle.

As per the research, the study describes what the authors call “3D necroprinting,” in which proboscides taken from laboratory-reared, uninfected and deceased mosquitoes are mounted onto a custom printer and used to extrude viscous inks and bioinks through a channel typically about 20 to 25 µm wide. Because this is smaller than common commercial micro-dispense tips, the system can produce printed lines on the order of 18 to 28 µm, with demonstrations around 20 to 22 µm.

“High-resolution 3D printing and microdispensing rely on ultrafine nozzles, typically made from specialized metal or glass,” said study co-author Jianyu Li, Associate Professor and Canada Research Chair in Tissue Repair and Regeneration at McGill. “These nozzles are expensive, difficult to manufacture and generate environmental waste and health concerns.”

Evaluating the mosquito proboscis nozzle

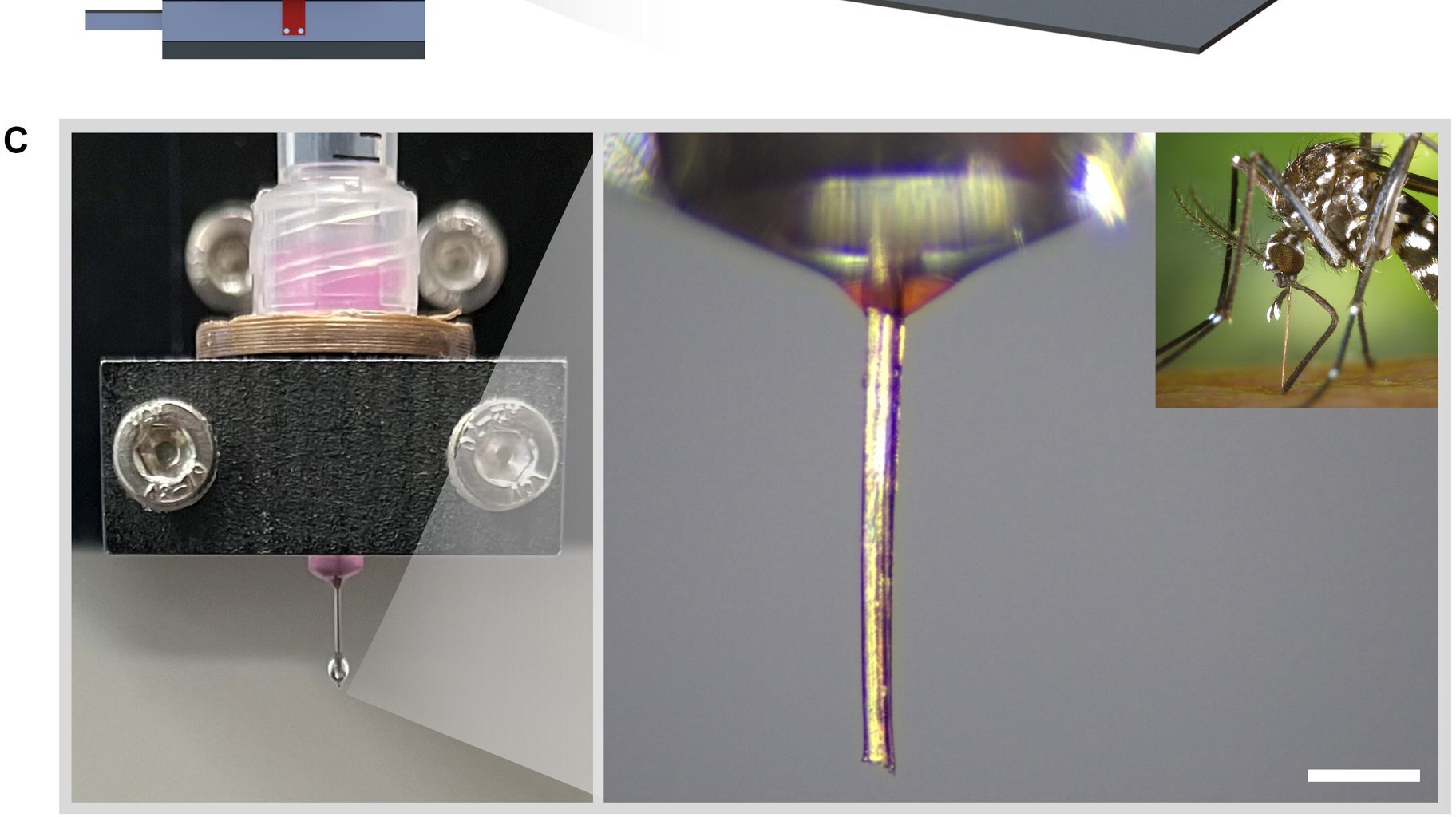

The researchers began by surveying many biological structures that naturally transport fluids, including stingers, fangs, harpoons, claws, plant xylem vessels, and insect proboscides. They selected the female mosquito proboscis because it is relatively straight, stiff for a biological material, easy to handle, and already forms a sealed hollow tube for feeding. Its inner diameter is around 20 to 25 µm and its length is about 2 mm, which is short enough to limit backpressure while remaining practical to mount.

Mechanical testing showed that the proboscis can tolerate internal pressures of about 60 kPa before rupturing. Burst tests combined with a thin-walled pressure vessel model indicated that failure is governed by circumferential stress in the wall, with an estimated critical hoop stress at failure of roughly 708 kPa. When failure occurs, it takes the form of an axial crack along the length of the proboscis.

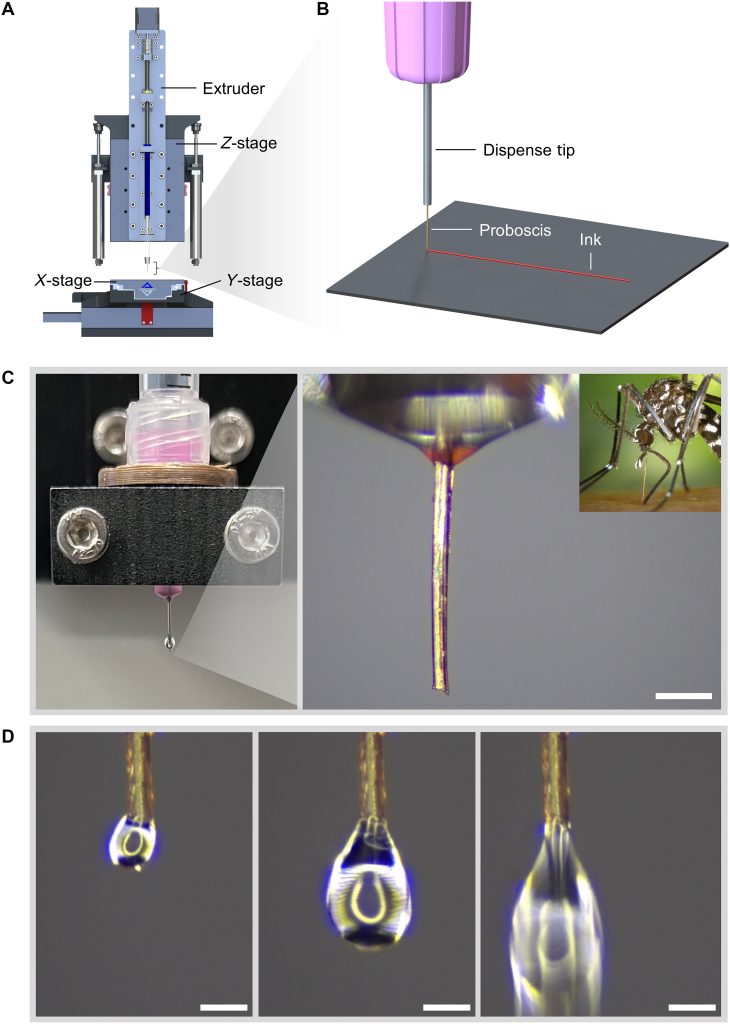

To use it as a nozzle, the team bonded the proboscis to the outlet of a standard syringe tip using a small adapter and UV-curable resin, creating a continuous flow path. The printer is a custom-built direct ink writing system with a piston-driven extruder and a high-resolution motion stage. The team demonstrated extrusion of commonly used bioinks, including Cellink Start bioink gel and Pluronic F-127 bioink gel.

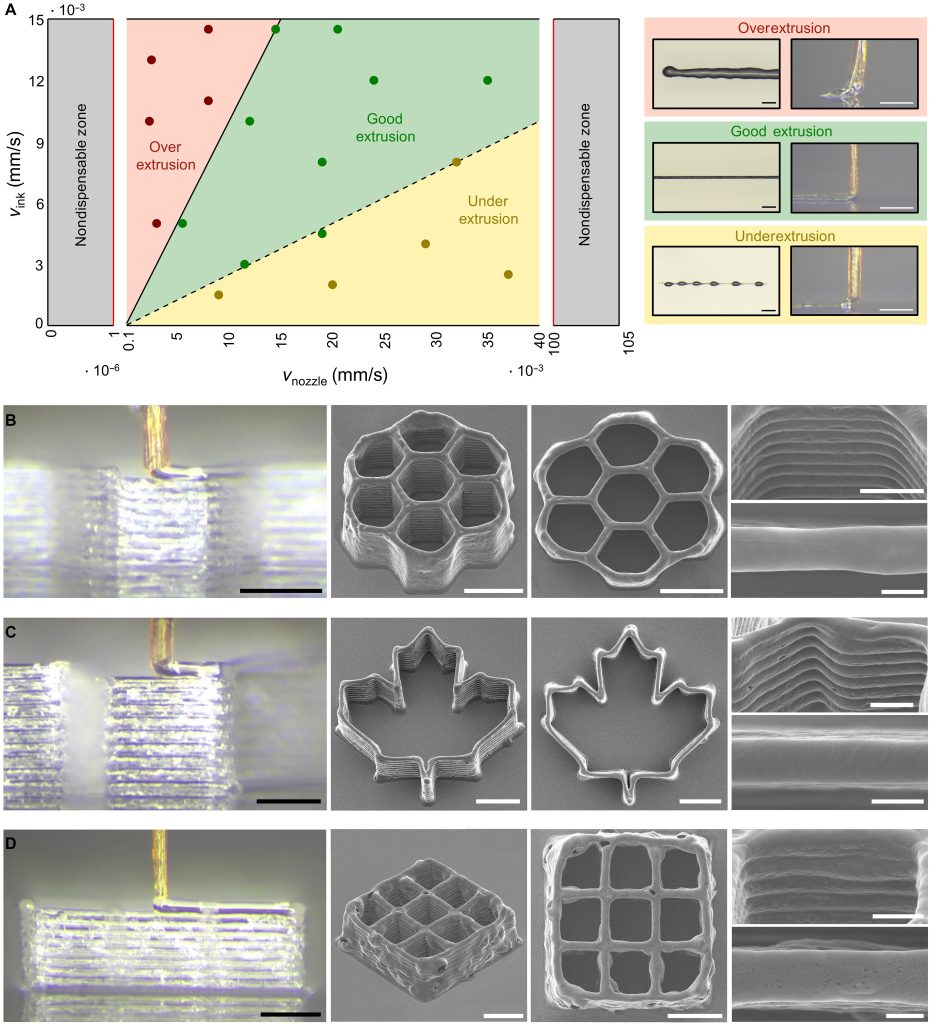

Two main failure modes were observed. In one, shear-thinning ink accumulated near the outlet and partially solidified when shear stress was removed, creating a blockage and a local pressure buildup that caused rupture near the tip. In the other, inks with very high apparent viscosity required so much backpressure that the proboscis ruptured near its inlet. Using rheological measurements and the Herschel-Bulkley flow model, the authors defined operating limits that avoid both types of failure.

They also identified a process window that balances ink extrusion speed and nozzle movement. Within this window, the system printed structures including a honeycomb about 600 µm across, a maple leaf about 900 µm across, and grid scaffolds. Some printed lines reached widths of about 18 µm.

The group also printed cell-laden inks containing B16 melanoma cells and red blood cells. Printed scaffolds showed a post-printing cell viability of about 86%, indicating that shear stresses in the biological nozzle did not cause widespread cell damage. A proof-of-concept test also showed uptake and redeposition of small volumes of hydrogel into a tissue analogue.

Compared with glass-pulled pipettes, which can reach diameters below 1 µm but are brittle, variable, nonbiodegradable, and expensive, mosquito proboscides are biodegradable, consistent in size, and low cost. The study also found that proboscides remain usable for several days at room conditions and much longer when frozen, and that internal surface roughness has a negligible effect on flow.

The work does not propose universal replacement of conventional nozzles, but shows its potential as a low-cost, environmentally sustainable alternative to metal and plastic nozzles.

Pushing 3D printing to microscales

Beyond McGill, researchers at University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign reported a direct ink writing method called 3D printing by rapid solvent exchange (3DPX) that enabled fabrication of ultra-fine polymer fibers down to 1.5 µm in diameter using a 5 µm nozzle, with aspect ratios exceeding 3,400.

Using rapid solvent exchange, filaments solidified almost instantly at speeds up to 5 mm/s, preventing capillary breakup and maintaining stability. The team demonstrated centimeter-scale fibers, hair-like arrays, and curved structures, showed compatibility with multiple polymers and nanocomposites, and used multi-nozzle printing for parallel fabrication, establishing a new resolution benchmark for embedded direct ink writing.

Additionally, Stanford University researchers developed a roll-to-roll version of continuous liquid interface production (r2rCLIP) that used a moving PET film to replace a stationary build plate. This enabled a fully automated line for printing, washing, curing, and removing microscale parts at rates approaching one million particles per day.

Led by Joseph DeSimone’s group, the system demonstrated high-resolution, high-throughput micro-3D printing for scalable manufacturing in areas such as drug delivery, microrobotics, and advanced materials.

The researchers’ findings are detailed in their paper titled “3D Necroprinting: Leveraging biotic material as the nozzle for 3D printing,” by Justin Puma, Megan Creighton, Ali Afify, Jianyu Li, Changhong Cao, Evan Johnston, Hongyu Hou, Lingzhi Zhang, Zixin He, Zixin Zhang, Xiaoyi Lan, Zhen Yang et al, was published in Science Advances.

The 3D Printing Industry Awards are back. Make your nominations now.

Do you operate a 3D printing start-up? Reach readers, potential investors, and customers with the 3D Printing Industry Start-up of Year competition.

To stay up to date with the latest 3D printing news, don’t forget to subscribe to the 3D Printing Industry newsletter or follow us on LinkedIn.

While you’re here, why not subscribe to our Youtube channel? Featuring discussion, debriefs, video shorts, and webinar replays.

Featured image shows the concept and configuration of 3D necroprinting. Image via McGill University.