Gold has long played a peripheral role in Venezuela’s economic narrative, eclipsed by the country’s oil reserves, political crises and volatile policy shifts. Yet in the dense, forested expanses of Bolívar state, researchers have quietly confirmed the existence of one of the largest untapped gold deposits in the Western Hemisphere. It lies beneath ancient rock, shaped by billion-year-old tectonic events, in a zone few outside the mining or geological community have closely examined.

Much of the world’s gold is extracted from deposits formed over relatively short geological timescales. Venezuela’s differs. The country’s largest known mine was created not by a single event but by a long, complex interplay of heat, pressure and microscopic seismic activity.

Gold did not form in visible nuggets but became trapped inside iron sulphide, only later reassembled into recoverable veins. The process, difficult to detect without advanced tools, remained largely hidden until researchers connected scattered pieces of data into a clearer picture.

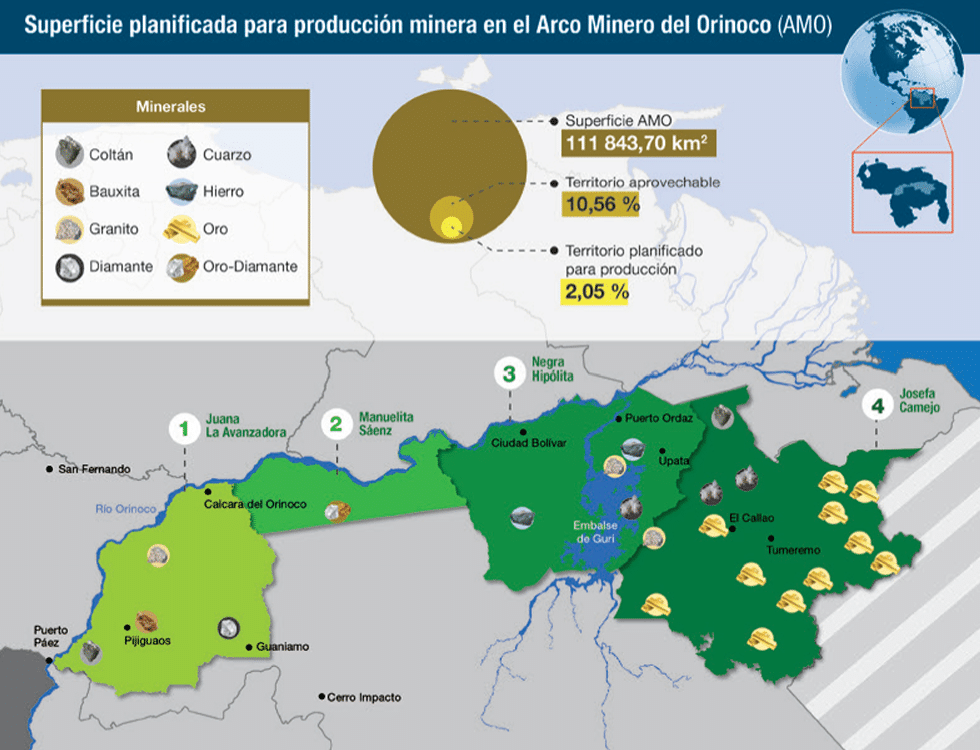

Meanwhile, the Orinoco Mining Arc, covering 111,000 square kilometres of southern Venezuela, is now officially designated for resource extraction. Government reports point to vast reserves of iron ore, bauxite, coal, and nickel, alongside gold. On paper, these figures place Venezuela among the more resource-rich nations in the region. In practice, much of this potential remains unexploited.

One of the largest known gold deposits in the Guiana Shield

Located in the El Callao district, the Colombia mine contains an estimated 740 metric tonnes of gold, according to official government figures and academic analysis. This figure, well above the 500-tonne threshold for classification as a “giant deposit,” places it among the most significant gold resources in South America. The mine is part of the Guiana Shield, a geological formation stretching across several countries, known for its ancient rocks and mineral concentrations.

Detailed research published in 2012 by geologist Germán Velásquez describes the gold-bearing structures as a complex network of veins cutting through Proterozoic basalt. These rocks, over two billion years old, once formed part of the ocean floor. The gold is primarily associated with pyrite (iron sulphide), within which it is hosted at the microscopic level.

The study found that most of the gold initially existed as “invisible gold”, embedded in the crystal structure of pyrite or trapped within submicroscopic inclusions. Over time, a series of microseismic events triggered remobilisation, concentrating the gold into more accessible zones. This two-phase process, both rare and technically significant, is outlined in Velásquez’s doctoral thesis and makes the Colombia deposit one of the few in the region to combine scale with extractable quality.

A broader mineral inventory with limited development

Beyond gold, Venezuela’s Ministry of Mining and Ecological Development published a comprehensive mineral catalogue in 2018 estimating substantial reserves across multiple commodities:

14.68 billion tonnes of iron ore

3 billion tonnes of coal

321 million tonnes of bauxite

44 million tonnes of nickel ore

1.02 billion carats of diamonds

262 million tonnes of gold-bearing ore, equivalent to 644 tonnes of refined gold

The figures, while significant, have not been updated in recent years. They remain unaudited by external agencies and lack transparent technical documentation. Volumes for coltan and rare earth elements, also identified in government plans, were not included in the published data.

Comparatively, Venezuela’s reserves of iron, bauxite and nickel are moderate on the global scale. Major producers like Australia, Brazil and Russia maintain considerably larger proven inventories. However, Venezuela’s geological context suggests potential for further discoveries, particularly in regions that remain underexplored due to limited infrastructure and logistical challenges.

Geological processes shaped by ancient tectonic history

The formation of the Colombia deposit is tied to the Transamazonian orogeny, a tectonic event that occurred over 2 billion years ago. As the Guiana Shield collided with adjacent geological blocks, it created zones of intense deformation. In these zones, hydrothermal fluids containing water, carbon dioxide and sodium chloride circulated through fractured rock.

According to Velásquez’s findings, these fluids, combined with repeated microseismic activity, triggered cycles of pyrite formation. Each new generation of pyrite crystallised in fragments of Proterozoic basalt, incorporating trace amounts of gold. Over time, this “invisible gold” was remobilised into structurally favourable corridors. These corridors, now mapped and studied, define the deposit’s most economically viable zones.

A 2000 geological study published in the Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France further supports this tectonic framework, examining the structural and geochemical factors that contributed to gold mineralisation in the Guiana Shield and adjacent regions. The study identifies a pattern of mineral deposition consistent with the hydrothermal remobilisation process observed in Venezuela.

But, despite its geological promise, Venezuela’s mining sector faces significant barriers. Foreign investment is limited by political instability, sanctions and unclear regulatory frameworks. Infrastructure around the Orinoco Mining Arc remains sparse, with few large-scale operations active beyond artisanal and semi-industrial levels.