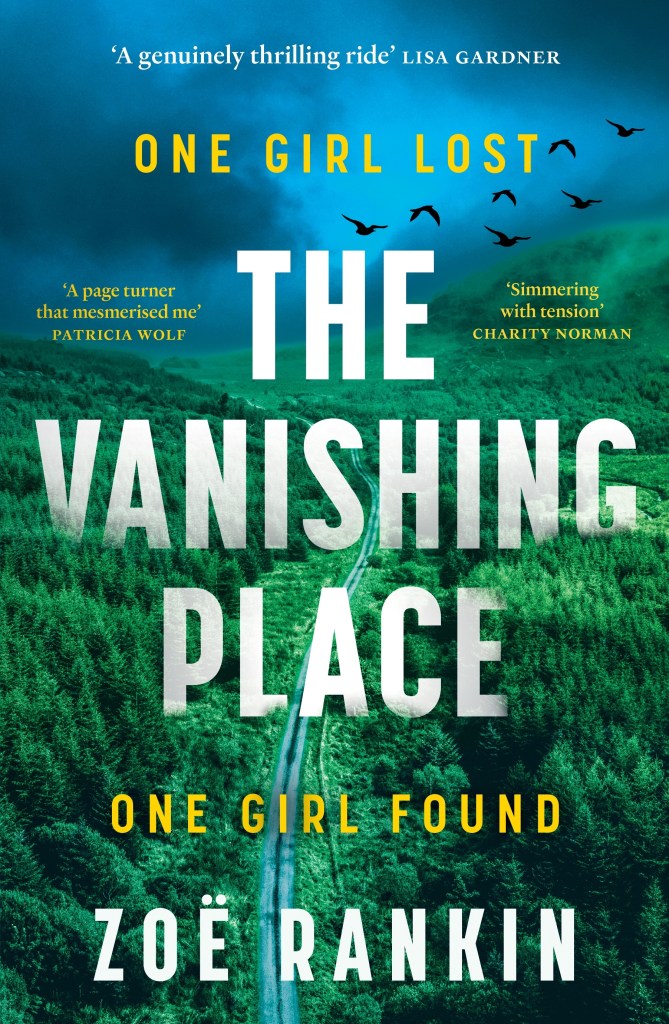

You can view the new number 1 bestselling New Zealand novel The Vanishing Place by Zoë Rankin as a kind of mash-up of the Tom Phillips case and Gloriavale, with its plot lines about a family hiding in the bush and a religious cult with hardcore Old Testament rules of conduct. You can read it as a thriller. You can read it as one of the best novels ever set in the dense, creepy New Zealand bush. You can read it with the same kind of pleasure people are reading it around the world: rights were sold to the US and the UK in the month after its publication in New Zealand. There are all sorts of options open to you but the main thing is that you should just buy it, and allow yourself to be immersed in the dark world that Rankin creates.

It opens in 2025. A little girl wanders out of the bush and heads straight for the only shop in the fictional town of Kohara. She stuffs herself with strawberries and milk. The local cop is summoned. “She would be one of those children now,” the kid thinks. “One of the children whose faces filled the front pages of those dangerous newspaper things.” From there, the book tells alternating chapters, set in 2025 and 2001. The police investigation in 2025 is tense and mysterious. The events in 2001 tell a competing narrative of a family of four kids – the mother of the youngest dies in childbirth, and the baby is henceforth only known as Four – stranded in dense bush with their brooding father, who disappears for days at a time. Subtly, cleverly, Rankin joins the dots between 2001 and 2025.

The heroine is the youngest daughter of the 2001 family, Effie. She grows up, escapes her father, and establishes a new life as a police officer in the Isle of Skye in Scotland. But she returns to Kohara when word reaches her that she’s the spitting image of Anya, the little girl who likewise has left her family and beaten her way out of the bush. The bush is everywhere in The Vanishing. When characters step out of it, it remains as a dark, menacing presence; and characters are forever stepping back into it. Rankin gets the feel of it just right. “He was wearing his waterproof poncho and he was waist-deep in water, already a third of the way across the river. Effie blinked against the rain as she tried to shout, but the sky was heavy; it squashed her voice.”

Anya talks of dead bodies back in a hut in the bush. It’s the same remote hut where Effie was raised. “The route was ingrained in her. Every land marker. Every bend in the river. As the oldest child, she had the bush etched into her skin.” The bush is etched into every page. Effie leads the police to the hut, and the reader is taken with her, too. You can smell the ground, hear the wind in the trees. “Kahikatea and miro and solid forest.” The book is set in Haast (“Greymouth and Christchurch are the nearest cities for anything important”) but it could be any New Zealand wilderness in either island, including Stewart Island.

The Phillips case roams the edges of the book, as characters talk of child welfare services and calling in Oranga Tamariki, and the portrait emerges of Effie’s Dad as a law unto himself. Gloriavale edges closer as the book progresses, and we meet members of a cult that follows the law of God as enforced by the patriarchy. There are a few moments of light relief. They are very few, and not very relieving. One character says, “TV I can live without. But not my morning dose of Corin and Ingrid.” The same lame joke about a dog that likes sleeping on Effie’s bed in the Isle of Skye is made over and over, and remains lame. You don’t actually want light relief. You come to The Vanishing for a bad time. The bush, as Rankin evokes it, is like a drug: it’s all you want, its darkness and threat, its hard rain and animal carcasses.

But you can have too much of a bad time. The claustrophobia of the bush is only maintained for as long as the story is a credible imagining of strange people doing strange things. Rankin maintains it for about 200 wonderful pages. Effie’s hunt for the hut in 2025 is exciting; Effie’s childhood in 2001, and the next few years, is told with masterly skill. But the last third of the book falls apart.

A third, sudden plot line, of some incest hillbilly maniacs running around the bush in the late 1990s, arrives like an unwelcome guest, and over-complicates the plot. Rankin contrives a sex scene for Effie, and thuds at the page with 10 thumbs: “He pulled her close, his mouth forceful, and Effie sank into him, her heart pounding as he lowered her to the sand.” And: “He kissed her from her navel up to her neck.” Wrong way, mate! Around this time, a theory develops that someone has died from poison tutu, cult members chant from the Bible, and Effie thinks, “Her sister has lived through hell. There were no words for that.” But it’s a book, and words are kind of helpful. The last 50 or so pages are an orgy of exposition, as Everything Is Explained, and the final drama is presented in the cliched format of short little single-sentence paragraphs: “A bright white light, flooding her vision.” Then: “Crack.” Then: “A body.” Oh. What. Ever.

In an interview with Rotorua Daily Post journo Annabel Reid, Rankin said, “You can disappear into the bush. No one can find you.” She develops that sense brilliantly and convincingly throughout her debut novel. Reid wrote in her interview, “You could even hide from police, Rankin said, a reality she realised after following the Tom Phillips case.” The creepiness of that case runs like a black river through the pages of The Vanishing. The opening two-thirds is a tour de force. But too many threads are chucked in and tied up in neat bows, and the power of the book recedes, erodes, is washed away, vanishes.

The Vanishing Place by Zoë Rankin (Hachette, $37.99) is available in bookstores nationwide.