The Beachy Head Woman study shows a 2,000-year-old skeleton at Beachy Head in southern England belonged to a local woman in Roman Britain.

A London museum team used newer DNA and chemistry tests to revisit a debate that shaped public views of ancient migration.

Faster sequencing and bigger reference datasets reopened the Beachy Head Woman study after early tests left too much uncertainty.

The work was led by Dr. Selina Brace at the Natural History Museum (NHM) in London. Her research uses bones and genomes, complete sets of DNA instructions, to test how people moved during Roman rule.

Naming the “Beachy Head Woman”

A cardboard box found in Eastbourne Town Hall held a skeleton labeled Beachy Head, with notes pointing to the 1950s.

Missing excavation notes forced scientists to rely on radiocarbon dating, which is measuring carbon decay to estimate age, from a small bone sample.

The range of CE 129 to 311, meaning the years 129 to 311 of the Common Era, comes from a calibration curve that translates radiocarbon measurements into calendar dates

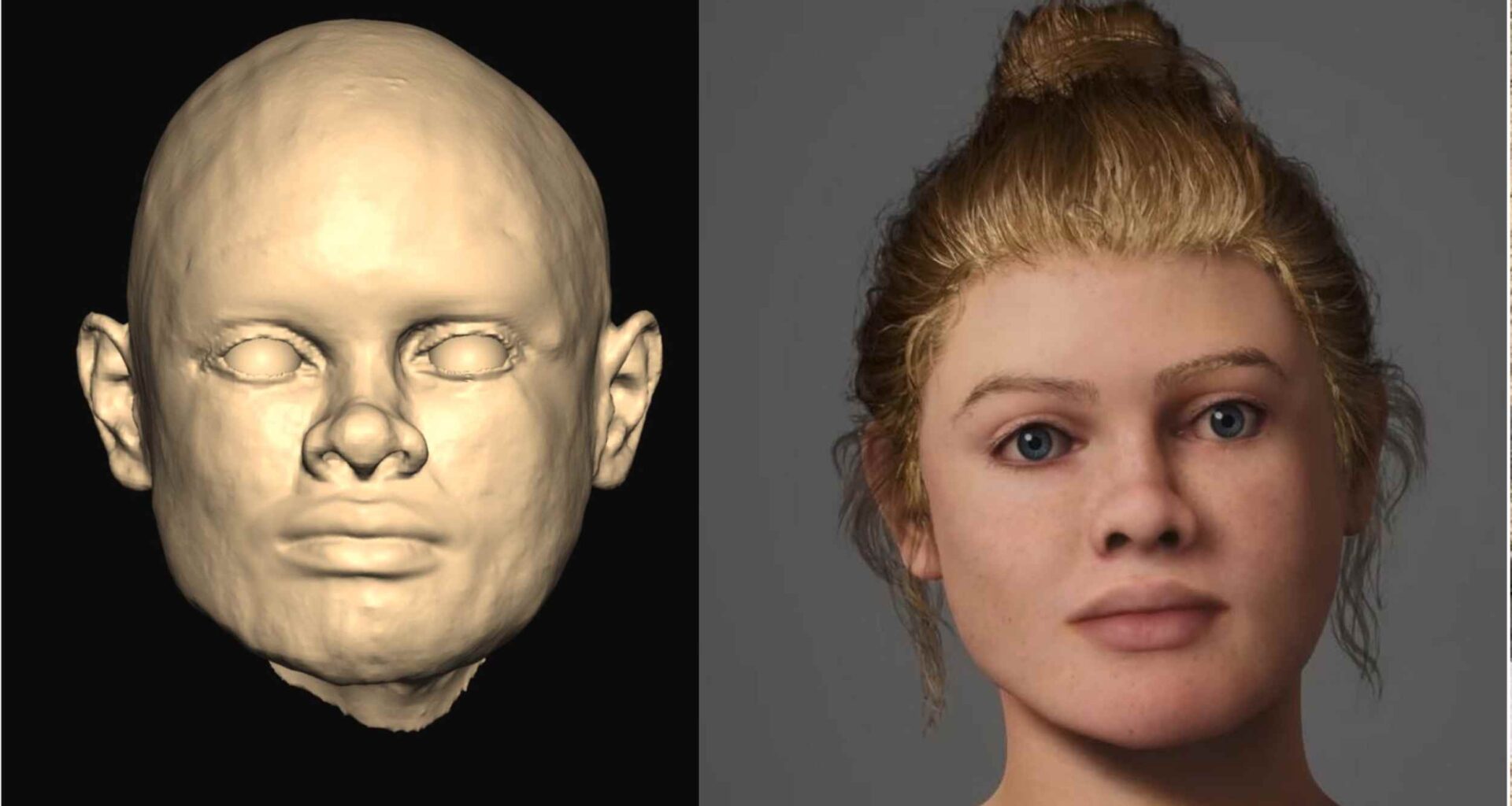

Bone measurements from the skull suggested sub-Saharan African roots, and the idea quickly spread through books, classrooms, and exhibits.

That approach used craniofacial morphology, comparing skull shapes across reference groups, yet traits overlap widely across human populations.

Once the skeleton became a symbol of early African presence, later corrections had to compete with a familiar public story.

Years later, lab teams could recover far more ancient DNA, genetic material preserved in long-dead cells, than earlier tests managed.

Researchers drilled powder from the dense petrous bone, then used targeted capture to pull out key human markers.

Better recovery mattered because early fragments once hinted at Cyprus, yet low coverage can mislead when too few sites read clearly.

Before ancestry results mean anything, labs must show the sequences are truly old and not modern mix-ups.

Damage patterns at fragment ends, plus low contamination, modern DNA accidentally added to samples, helped authenticate the remains.

At NHM, those checks set boundaries on confidence, especially when one person is used to represent a whole community.

Bone and teeth chemistry

Chemical clues in teeth track where a person spent childhood, because enamel locks in local water signatures.

The team measured isotopes, atoms of the same element with different weights, in tooth enamel and bone collagen.

Values matched Britain’s south coast ranges, so long-distance childhood migration looked unlikely for this individual.

Carbon and nitrogen signals in bone collagen hint at what someone ate over years, not just days.

Higher nitrogen values fit a seafood-heavy menu, and that aligns with a life spent near the Channel coastline.

Diet data can be noisy, but the pattern supported other evidence for a coastal upbringing and routine local movement.

Age, injuries, and stature

Skeletal features placed her age at death between 18 and 25 years, a narrow window for such old remains.

Stature estimates put her at about 5 feet and leg healing showed survival after a serious wound.

Because bones rarely reveal cause of death, the Beachy Head Woman study focused on lived experience rather than a final moment.

Where her genes clustered

Large comparison datasets let scientists see which groups share the most genetic variants, even when samples are incomplete.

Her ancestry pattern aligned with rural southern Britain, and the results matched many modern people from England.

No clear signal pointed toward recent African or eastern Mediterranean ancestry, narrowing the range of plausible life histories.

Predicting visible traits carefully

Pigmentation predictions draw on gene variants tied to eye, hair, and skin traits, and they come with uncertainty.

The team used phenotype, outward traits shaped by genes and environment, markers to suggest blue eyes, light hair, and intermediate skin.

A revised digital face model followed those cues, yet bones still set most facial-shapes and fine details stay unknown.

Why skull traits can mislead

Skull-based ancestry labels often assume clear boundaries, even though genetic differences usually grade smoothly across regions.

A professional statement notes that clinal, gradual change across geography over many generations, patterns make rigid skull categories unreliable.

Using multiple lines of evidence can correct these errors, but only if researchers stay open about uncertainty and revision.

Beachy Head Woman and Roman Britain

Roman Britain drew people from many places, because the empire moved soldiers, traders, and families along its roads and ports.

Archaeologists have documented long-distance newcomers through burials, objects, and isotopes, showing that mobility was part of daily life.

The Beachy Head Woman study therefore narrows one biography, not the wider history of movement during Roman rule.

Once an identity story lands in a gallery, it shapes how visitors see the past and each other.

“She’s had quite a journey,” said Dr. Brace after the new results arrived. Clear labels about methods and limits help avoid turning tentative inferences into permanent facts that outlive new evidence.

Together, genetics, isotopes, and bone biology show how this woman likely grew up locally, despite years of debate.

Future work will test other disputed skeletons with similar multi-method checks, while museums update displays without erasing past uncertainty.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–