Even if A.I. doesn’t greatly accelerate economic growth, there’s the issue of how it affects employment and wages. The key issue here is whether A.I. primarily complements or substitutes for human labor. If it enables office workers to carry out their tasks more quickly and effectively, for example, it could raise their wages, preserve many existing jobs, and create well-paid new positions for people who are adept at working with A.I. agents. In a recent article, Séb Krier, a manager for policy development and strategy at Google DeepMind, argued that “future workers will likely function as orchestrators of intelligence,” overseeing what A.I. does. Over the longer term, A.I. could also create new jobs and new professions that we can’t currently envision, which is what other transformative technologies have done.

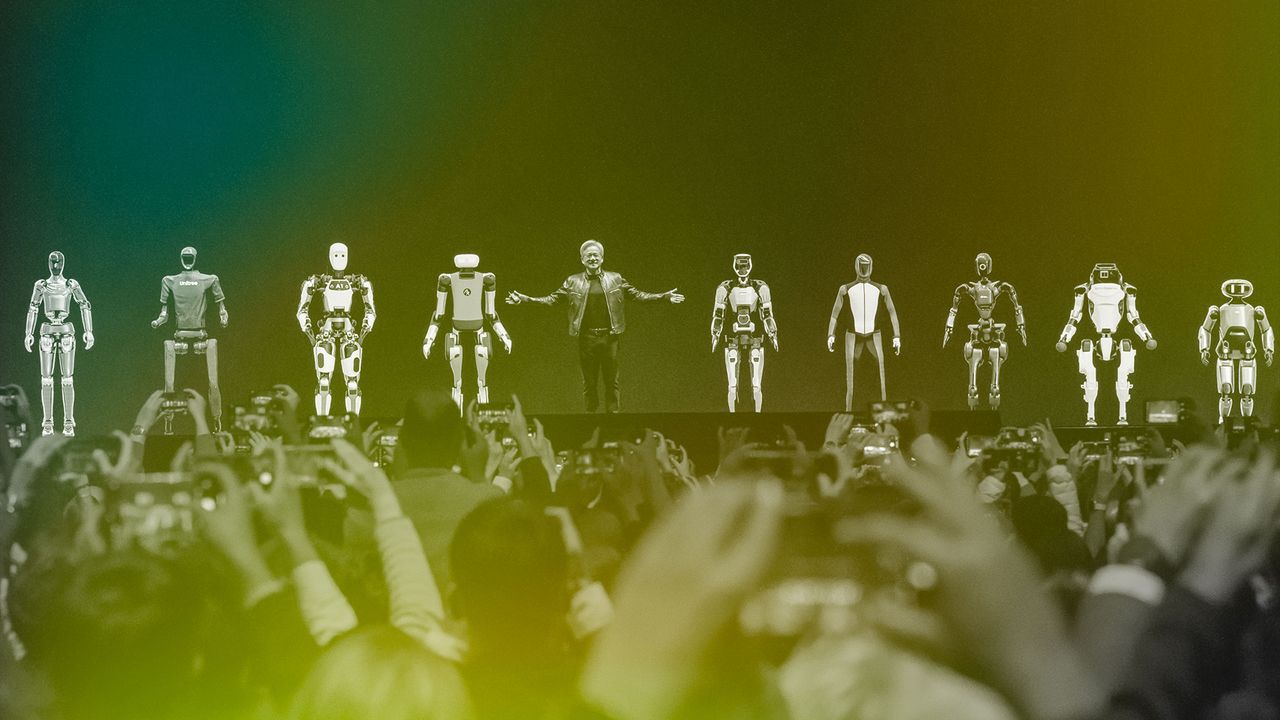

But the fact remains that if A.I. agents can eventually carry out virtually all cognitive tasks without human intervention—a possibility touted by their promoters—many workers could be displaced, and firms may be reluctant to take on new ones. Given the evolving capacities of models like OpenAI’s ChatGPT, Google’s Gemini, and Anthropic’s Claude, it’s perhaps unwise to wholly discount the prediction from Dario Amodei, the C.E.O. of Anthropic, that within five years A.I. could eliminate half of all entry-level white-collar jobs. Elsewhere in the economy, who knows what could happen? But if the marriage of A.I. and robotics proceeds, in other sectors, along the lines that it seems to be moving in the automotive industry, where autonomous vehicles are already being deployed in some places, taxi-drivers and truck drivers likely won’t be the only blue-collar workers whose jobs are affected.

“It’s clear that a lot of jobs are going to disappear: it’s not clear that it’s going to create a lot of jobs to replace that,” Geoffrey Hinton, one of the pioneers of the deep-learning models that underpin generative A.I., remarked at a conference last month. “This isn’t A.I.’s problem. This is our political system’s problem. If you get a massive increase in productivity, how does that wealth get shared around?” If A.I. abundance does materialize, that will be a central question.

In a recent Substack article, Philip Trammell, an economist at the Stanford Digital Economy Lab, and Dwarkesh Patel, a tech podcaster, pointed out that in standard economic theory deploying more capital raises workers’ productivity and their wages, but reduces the rewards of further capital investment as diminishing returns set in. This “correction mechanism” keeps the over-all shares of income that accrue to labor and capital pretty constant over time. But if A.I. is easily substitutable for labor throughout the economy, and a potential shortage of workers is no longer a bottleneck to production, the stabilization effect disappears, capital incomes “can rise indefinitely,” and the owners of capital receive an ever-growing share of the economic pie, Trammell and Patel write. How far can this process go? “[O]nce A.I. renders capital a true substitute for labor,” Trammell and Patel write, “approximately everything will eventually belong to those who are wealthiest when the transition occurs, or their heirs.”

Trammel and Patel relate their analysis to Thomas Piketty’s book “Capital in the Twenty-First Century,” from 2014, which argued that, under certain conditions, rising inequality is inevitable under capitalism. To address this problem, Piketty called for a global tax on wealth. Trammell and Patel argue that Piketty’s pessimistic analysis hasn’t applied until now, but “he will probably be right about the future.” They also endorse Piketty’s policy solution, writing, “Assuming the rich do not become unprecedentedly philanthropic, a global and highly progressive tax on capital (or at least capital income) will then indeed be essentially the only way to prevent inequality from growing extreme.” (The tax would have to be global, the authors argue, because if capital doesn’t need much labor to produce things it would be even more mobile than it is now, which would enable it to evade national levies.)

The article by Trammell and Patel has already received some pushback online, largely on the ground that its assumption that capital is perfectly substitutable for labor is unrealistic. Brian Albrecht, the chief economist at the Portland-based International Center for Law & Economics, argues that the process of A.I. machines replacing workers is likely to take a long time, and during that transition “standard economic principles apply.” Krier argued that the mere fact A.I. can do something more cheaply or effectively than human workers doesn’t mean it will inevitably replace them. “People pay a lot to go see concerts and Olympic races even if in principle a model can generate the same song and a robot can run faster,” he wrote.