A mining-machine test on the deep-ocean floor resulted in species diversity declining by roughly 32% in the tracks of the mining equipment.

Researchers worked in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ) between Mexico and Hawaii, where deep-sea mining is tested.

Over five years, crews spent 160 days at sea to sample seafloor life before and after the collector crossed the sediment.

The collector gathered 3,300 tons of polymetallic nodules, rocks holding nickel and cobalt, from a depth of 2.7 miles (4.3 kilometers).

The work was led by Dr. Adrian Glover at the Natural History Museum, London (NHM), which houses major ocean collections.

His research focuses on describing deep-sea species and using DNA to track how seabed communities respond to disturbance.

Scientists used a Before-After-Control-Impact approach, a design comparing controls and disturbed sites, to separate mining effects from natural change.

Life on the abyssal plain

The site sits on an abyssal plain, a vast flat seafloor region, where falling organic scraps feed most animals.

Even without mining, the community changed through the study. Researchers suggest this likely reflects surface-ocean productivity, which controls how much food reaches deep sediments.

Researchers sorted 4,350 animals over 0.01 inches at NHM and identified 788 species in and on sediment.

Most specimens were marine bristle worms, crustaceans, and mollusks, showing how much hidden variety fits inside a small boxcore.

Creatures in a working test field

Among the finds was a solitary coral, Deltocyathus zoemetallicus, attached to nodules and unknown to science before this survey.

Some of the most common animals were bristle worms about 0.04 to 0.08 inches long. The haul also included tiny sea spiders, distant relatives of land spiders, and other groups rarely collected in this region.

Scientists still cannot say how far many species range, so biodiversity varies across nearby seafloor patches.

Mining tracks and ocean species

In the collector tracks, the community became more uneven from place to place, a sign that the disturbance scrambled local patterns.

Researchers saw stronger swings in which species dominated, even when the total species pool looked similar after accounting for sample size.

Macrofauna, animals big enough to sort by hand, mostly occupy the upper inch of sediment disturbed by nodule collectors.

Samples in a sediment plume, a drifting cloud of stirred-up mud, showed no clear density drop, but dominance changed.

DNA turns mud into a species list

Because most creatures lacked formal names, the team used DNA barcoding, matching species by short standard gene sequences, to group specimens.

Specialists worked from shared codes at NHM and matched DNA data, so each specimen stayed traceable when it moved between labs.

Extrapolation suggested the contract area may hold 1,148 to 1,391 macrofaunal species, far beyond what sorting has captured so far.

Rarefaction curves, plots showing species counts as sampling grows, kept rising and warned researchers that many rare animals still went unsorted.

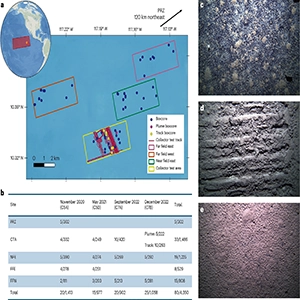

Impact of deep-sea mining on ocean species biodiversity and ecosystems. Overview of study region, sampling design and example seafloor morphology. Credit: Nature. Click image to enlarge.Rules written by a global regulator

Impact of deep-sea mining on ocean species biodiversity and ecosystems. Overview of study region, sampling design and example seafloor morphology. Credit: Nature. Click image to enlarge.Rules written by a global regulator

In international waters, the International Seabed Authority (ISA), the United Nations body overseeing seabed minerals, sets rules for contractors and scientists.

The ISA requires an environmental impact assessment, a report estimating harm before a project starts.

Those rules also push for a baseline survey, data collected before disturbance for comparison, so natural swings do not masquerade as impacts.

Scientists sampled control areas outside the mining tracks, because the ISA needs reference sites to judge real damage.

Electric vehicles and wind turbines rely on critical minerals, materials judged vital and at supply risk, such as nickel and cobalt. A market review says demand and investment keep rising, yet new supply can lag for years.

Nodule mining attracts interest because one seafloor harvest in the CCZ can bring several battery metals without digging through mountains of rock.

At the same time, many governments and scientists urge caution because deep ecosystems recover slowly and the rulebook is still evolving.

How slow geology changes the stakes

An ISA factsheet says nodule growth is about 0.4 inches over several million years.

That timing matters because nodules act as hard habitats, and removing them also removes the homes of attached animals.

A collector track can stay visible for decades when sediment falls slowly, leaving compacted strips that do not refill fast.

Mining equipment also stirs particles, makes noise, and adds light, spreading stress beyond the exact path of the machine.

Species recovery after ocean mining

A later paper reported altered seafloor communities persisted for decades after a mining trial, despite some recolonization.

Some patches showed early return of mobile animals, but many spots still lacked the larger creatures that use nodules.

Those results raise practical questions about how long any monitoring must run, and who pays for decades of checks.

Because the latest trial measured change soon after disturbance, it cannot yet show whether the local community rebounds or stays changed.

Protected zones still need basic biology

About 30% of the CCZ is set aside as protected blocks, yet surveys remain too sparse to map what lives there.

Without solid maps of species and habitats, regulators cannot place no-mine zones wisely or predict which losses would be permanent.

Future work must track recovery for years, sample the protected blocks, and report methods openly so decisions rest on evidence.

The study is published in Nature Ecology & Evolution.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–