The search for habitable worlds beyond the solar system now faces a more technical obstacle than distance: uncertainty in the data itself. As space telescopes grow more precise, so too does the complexity of interpreting what they see—particularly when trying to determine whether molecules like water vapour or oxygen originate in an exoplanet’s atmosphere or in the volatile light of its host star.

NASA’s Pandora mission, now in orbit, is designed to address this ambiguity. Rather than discovering new planets, it will re-examine known ones, focusing on the fine line between planetary signal and stellar interference. The outcome could reshape how scientists read the atmospheres of distant worlds—and how confidently they search for signs of life.

A Focused Satellite for Precision Transit Observations

Launched on January 11 aboard a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket, Pandora has successfully separated and reached a stable, sun-synchronous orbit. NASA confirmed the satellite’s successful deployment shortly after launch, marking the start of its commissioning phase. Developed under NASA’s Astrophysics Pioneers program, Pandora is designed to observe light from stars and planets during repeated transits and to record it across visible and near-infrared wavelengths.

NASA’s Pandora space telescope satellite is in sun-synchronous orbit following separation of SpaceX’s second stage on Sunday, Jan. 11, 2025. A SpaceX Falcon 9 carrying Pandora, and several other payloads launched at 5:44 a.m. PST from Space Launch Complex 4 East at Vandenberg Space Force Base in California. Credit: SpaceX

NASA’s Pandora space telescope satellite is in sun-synchronous orbit following separation of SpaceX’s second stage on Sunday, Jan. 11, 2025. A SpaceX Falcon 9 carrying Pandora, and several other payloads launched at 5:44 a.m. PST from Space Launch Complex 4 East at Vandenberg Space Force Base in California. Credit: SpaceX

NASA reports that the mission will conduct detailed observations of 20 confirmed exoplanets, each observed over 10 full transit cycles. Each observation will span 24 hours, allowing measurements of the system before, during, and after the planet passes in front of its star. These long baselines are critical to identifying how much of the observed signal is due to the planet and how much may be introduced by the star itself.

The spacecraft’s optical system includes a 45-centimetre all-aluminium mirror, developed in partnership with Corning Incorporated, and a near-infrared detector originally built as a spare for the James Webb Space Telescope. Mission operations are managed at the University of Arizona, with data processing carried out by NASA’s Ames Research Center in California.

Disentangling Planetary Atmospheres from Stellar Activity

The challenge Pandora seeks to resolve is well established in exoplanetary science. During a transit, light from a star passes through the atmosphere of the orbiting planet, where molecules such as methane, carbon dioxide, or oxygen can absorb specific wavelengths, leaving identifiable signatures. However, stars are not uniform. Their surfaces often include bright regions, dark spots, and magnetic disturbances that can emit or absorb light in similar patterns.

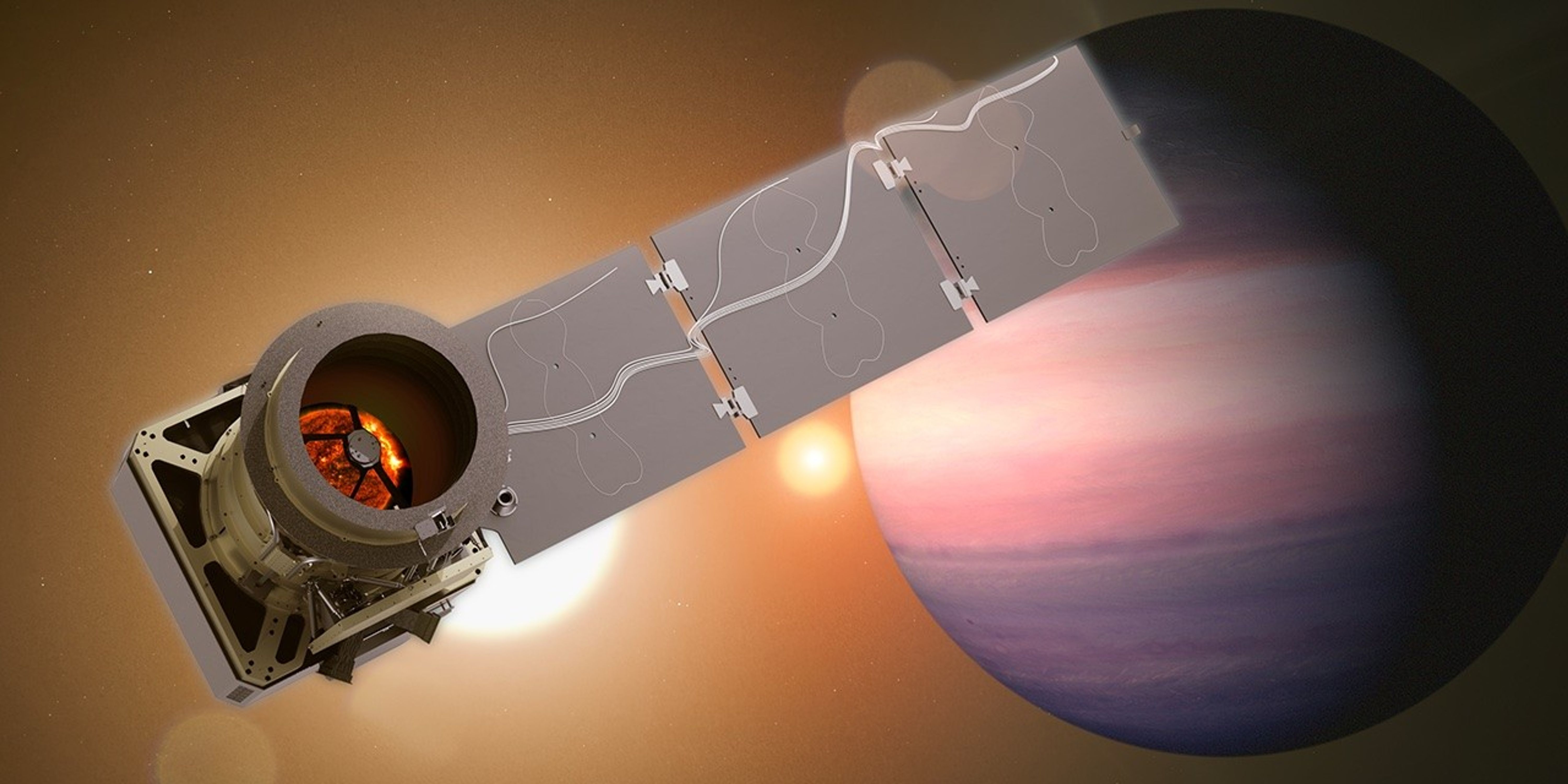

Artist’s concept of NASA’s Pandora mission, which will help scientists untangle the signals from the atmospheres of exoplanets — worlds beyond our solar system — and their stars. Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center/Conceptual Image Lab

Artist’s concept of NASA’s Pandora mission, which will help scientists untangle the signals from the atmospheres of exoplanets — worlds beyond our solar system — and their stars. Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center/Conceptual Image Lab

This overlapping spectral information introduces significant uncertainty. As explained in NASA’s mission overview on Pandora’s scientific objectives, even small features on a star’s surface can suppress or mimic signals from a planet’s atmosphere. Without accounting for these variations, observations risk misinterpreting the presence—or absence—of key atmospheric components.

“Pandora’s goal is to disentangle the atmospheric signals of planets and stars using visible and near-infrared light,” said Elisa Quintana, principal investigator at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. The mission’s dual-wavelength capability and extended transit observations are intended to isolate the influence of stellar variability, improving the fidelity of atmospheric data collected from other missions like TESS, Kepler, and Webb.

Complementary CubeSats and Broader Mission Framework

Pandora launched alongside two other CubeSats: SPARCS (Star-Planet Activity Research CubeSat) and BlackCAT (Black Hole Coded Aperture Telescope), both developed under NASA’s Astrophysics CubeSat program. All three spacecraft were part of the ELaNa 60 launch group, supported by the CubeSat Launch Initiative (CSLI), which provides low-cost access to orbit for academic and non-profit missions.

SPARCS, led by Arizona State University, will study ultraviolet flares from low-mass stars to evaluate their impact on orbiting planets. BlackCAT, developed at Pennsylvania State University, will use a wide-field X-ray detector to observe high-energy transient events such as gamma-ray bursts. These small missions operate independently but reflect a common trend: deploying specialised satellites to conduct focused science alongside larger observatories.

NASA notes that over 150 CubeSats have been launched under CSLI since the initiative began, many of which serve both educational and scientific roles. A detailed NASA briefing on CSLI outlines how the program supports hands-on flight hardware development and mission experience for students and faculty. Blue Canyon Technologies supplied the spacecraft bus for Pandora and SPARCS, while Livermore National Laboratory led mission systems engineering and integration for Pandora.

Data Access, Scientific Value, and Next Questions

Once operational, Pandora will enter a one-year primary mission phase. NASA has confirmed that all scientific data will be made publicly available, supporting planetary scientists, atmospheric modelers, and telescope operators seeking to refine their interpretations of distant planetary systems.

Unlike larger flagship missions, Pandora is not designed to discover new exoplanets or perform broad surveys. Instead, its contribution lies in improving the signal reliability from known systems. This could help prioritise future observation targets and assist in reinterpreting earlier measurements affected by stellar contamination.

With longer-term projects like the Habitable Worlds Observatory under development, establishing methods to reliably subtract or account for stellar interference has become a strategic priority. Data from Pandora may help define detection thresholds and correction algorithms for future telescopes tasked with identifying biosignatures on rocky exoplanets.

Several questions remain. To what extent can stellar noise be systematically modelled across different star types? How variable are planetary atmospheres over the timescales Pandora will observe? And what limits still exist in separating planetary chemistry from stellar physics, even with extended and multi-band measurements?