Scientists may have finally cracked a decades-old mystery about the Moon’s uneven surface. A new analysis of dust collected from the lunar far side shows strong chemical evidence of a violent impact that could have reshaped the Moon from the inside out, according to researchers from the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

This finding, based on samples returned by China’s Chang’e-6 mission, points to the immense role ancient collisions may have played in sculpting the Moon’s structure.

The Moon’s Far Side, Finally in Hand

Since 1959, when the Soviet probe Luna 3 first revealed images of the Moon’s far side, scientists have tried to understand why the two halves of the Moon look so different. Various explanations have been proposed, but the lack of physical samples from the far side left a critical gap in the evidence.

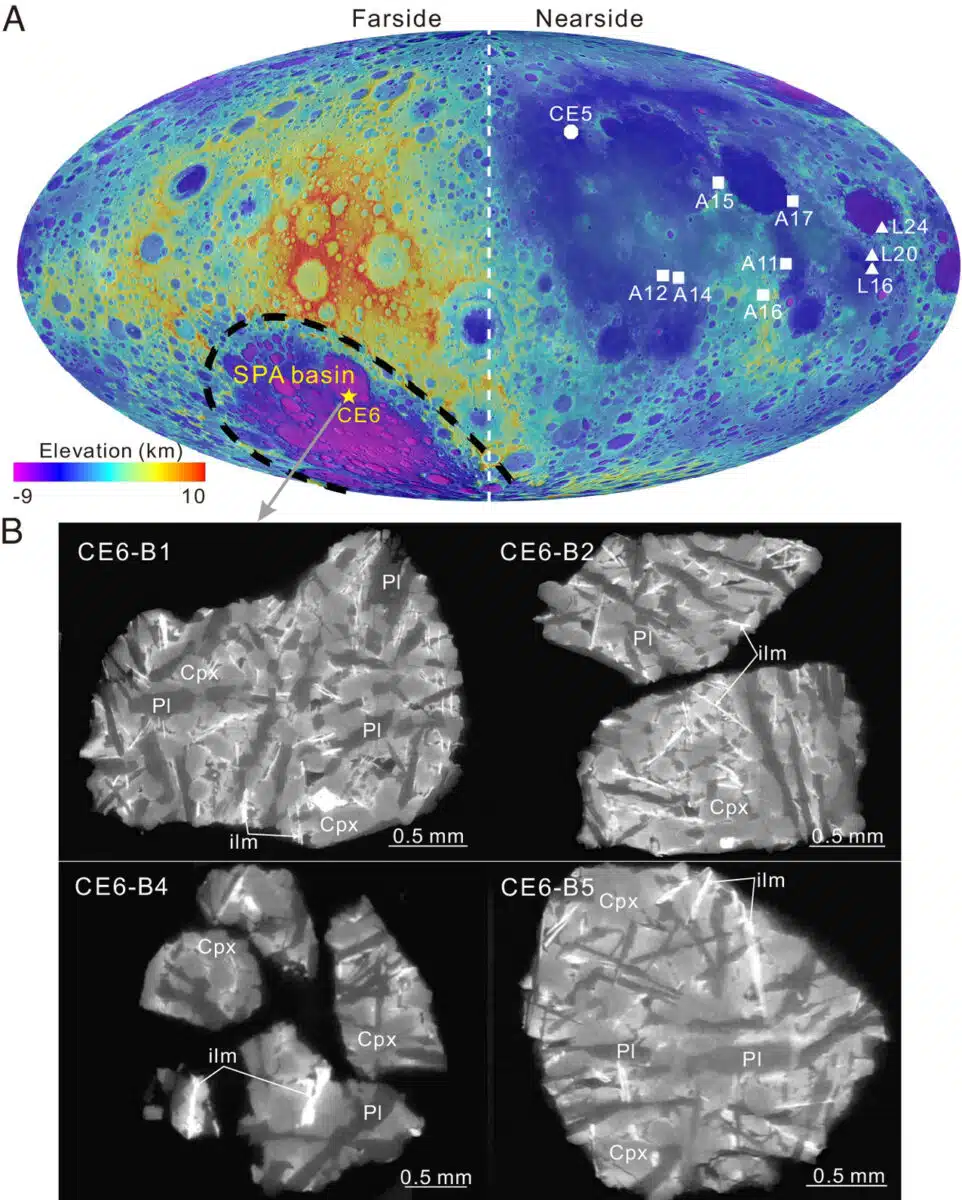

That changed when China’s Chang’e-6 mission returned with the first-ever dust samples from the Moon’s hidden hemisphere in 2024. The material came from the South Pole–Aitken Basin, a colossal crater that spans nearly a quarter of the lunar surface. This region, scarred by what is believed to be the largest impact in the solar system.

Isotope Clues Point to Deep Internal Change

Led by Heng-Ci Tian, a research team from the Chinese Academy of Sciences conducted isotopic analysis of the potassium and iron found in the far-side dust. According to the study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, these values were compared with samples from the Moon’s near side, previously gathered during the Apollo missions and by China’s Chang’e-5 spacecraft.

The results showed a significant difference. While near-side samples contained more light isotopes, the far-side material was richer in heavier isotopes, particularly of potassium. This type of isotopic separation could not be explained by normal volcanic activity, the team reported.

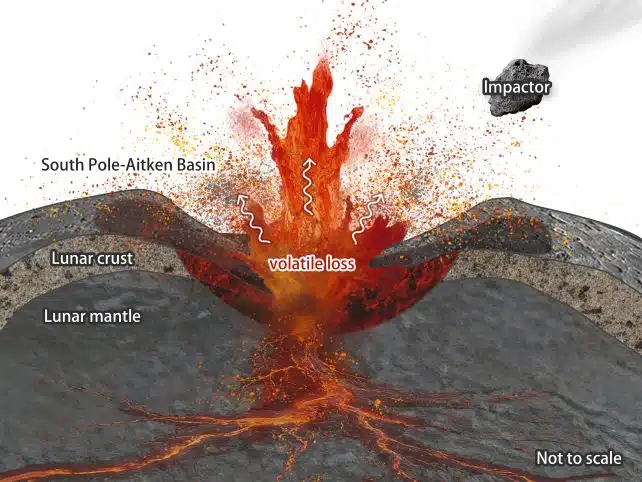

A quick sketch of the process behind the isotope differences. Credit: Heng-Ci Tian

A quick sketch of the process behind the isotope differences. Credit: Heng-Ci Tian

Instead, the researchers suggest that the South Pole–Aitken impactor generated such extreme heat that lighter isotopes were vaporized and lost, leaving behind a heavier chemical fingerprint.

“This feature most likely resulted from potassium evaporation caused by the South Pole-Aitken basin-forming impact, demonstrating the profound influence of this event on the Moon’s deep interior,” they wrote.

Signs the Moon’s Mantle Was Chemically Reworked

The idea that the Moon’s crust was altered by a collision is not new, but this study suggests the effects reached much deeper. According to the findings, the impact may have punched through the crust and into the mantle, permanently changing the Moon’s inner composition.

Moon topography map with cross-section micro-CT scans of four CE6 basalt specimens. Credit: PNAS

Moon topography map with cross-section micro-CT scans of four CE6 basalt specimens. Credit: PNAS

The sample analysis revealed that potassium isotopes on the far side appear to originate from a mantle source distinct from that of the near side. This implies that the collision caused widespread internal melting and chemical redistribution, leaving behind isotopic differences still visible today.

A Fresh Cheat Code for Lunar History

The study goes further by suggesting that large-scale impacts like this may be responsible for driving not only surface change but also internal planetary processes. The researchers propose that the impact might have even triggered hemisphere-wide mantle convection, a process that could reshape a planet’s crust and inner layers over time.

Although this possibility requires further investigation, the current evidence supports the idea that planetary impacts leave far more than visible craters. They may set off long-lasting internal transformations.

“This finding also implies that large-scale impacts are key drivers in shaping mantle and crustal compositions,” the team noted.

With the Chang’e-6 samples now under study, scientists have their first hard evidence from the Moon’s far side, an area once entirely out of reach.