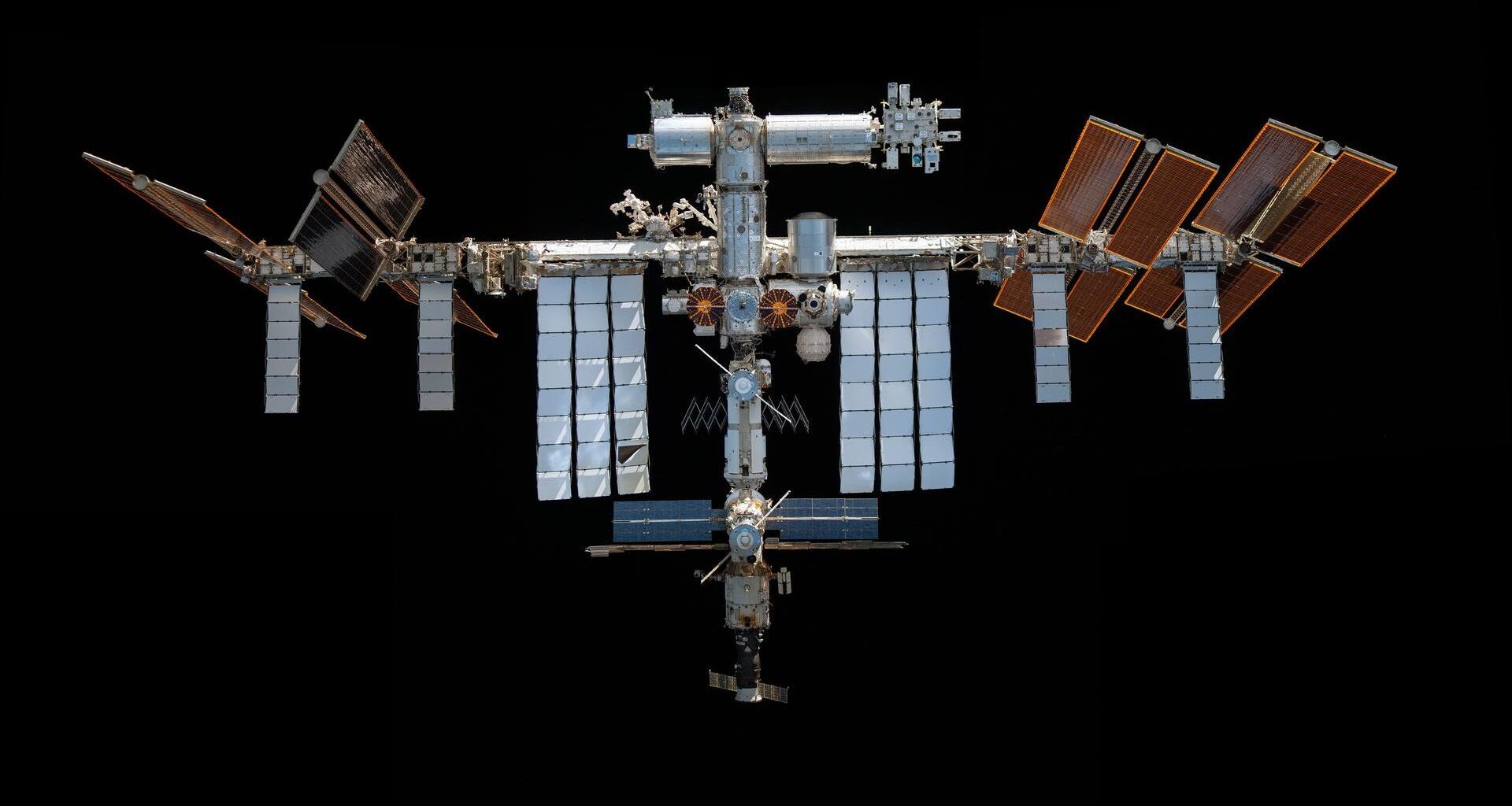

The International Space Station (ISS) is a closed ecosystem, and the biology inside it — including its microbial residents — don’t necessarily behave the same way on our home planet.

To better understand how microbes may act differently in space, researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison studied bacteriophages — viruses that infect bacteria, also called phages — in identical settings both on the ISS and on Earth. Their results, published recently in the journal PLOS Biology, suggest that microgravity can delay infections, reshape evolution of both phages and bacteria and even reveal genetic combinations that may help the performance against disease-linked bacteria on Earth.

“Studying phage–bacteria systems in space isn’t just a curiosity for astrobiology; it’s a practical way to understand and anticipate how microbial ecosystems behave in spacecraft and to mine new solutions for phage therapy and microbiome engineering back home.” Dr. Phil Huss, a professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and one of the study’s lead authors, told Space.com.

You may like

Bacteriophage basics

Bacteriophages, or phages, are the most abundant biological entities on the planet, with experts estimating around 1031 or ten nonillion bacteriophages on Earth. Not surprisingly, bacteriophages, a name meaning to “eaters of bacteria,” are found everywhere, shaping the microbial ecosystems in oceans, soils and even our bodies. But one place where phages may have the most human impact is as a possible treatment against antibiotic resistant bacteria and other bacterial infections.

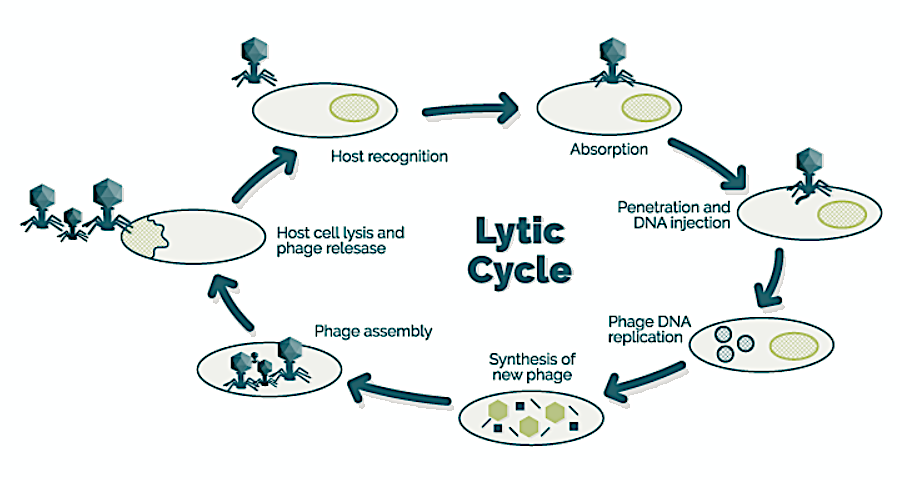

These phages work as tiny “delivery systems” wrapped in proteins. But unlike a delivery person giving a delicious pizza, some phages (like the T7 phage used in this study) infect bacteria by attaching to a specific surface feature on the cell — often a molecule embedded in the bacterial cell’s outer membranes — and injecting its genetic material. Once inside, the phage hijacks the bacteria’s machinery to make many copies of itself. Finally, it explodes the bacterial cell and releases a new wave of phage particles that can infect nearby bacteria.

This specific attack process by the phage then kicks off an evolutionary arms race between phages and bacteria, as bacteria can evolve resistance to these attacks by changing or hiding the phage’s “landing pad” found on the cell’s surface.

And things only get more complicated when microgravity gets involved.

A diagram showing the full lytic cycle of some phages. (Image credit: University of Barcelona, CC BY 3.0)A virus-bacteria showdown in orbit

To study how microgravity affects this process, the researchers used a bacteriophage called T7 and its bacterial prey, Escherichia coli, or what is more commonly known as E. coli. To isolate the effects of microgravity as cleanly as possible, the team prepared two identical sets of sample tubes of the bacteria, unshaken, and incubated at the same temperature for one, two or four hours, and a longer period of 23 days. One set of tubes went to the ISS in 2020, carried by Northrop Grumman‘s NG-13 Cygnus spacecraft while the other stayed below on Earth.

“The experiment had to work within strict NASA constraints: sealed cryovials had to pass biocompatibility and leak testing, withstand multiple freeze–thaw cycles, and remain safe to handle on orbit,” Huss explained. “The sample size is much lower than what we are used to terrestrially and designing an experiment around this is challenging!”

The team also varied the starting ratios of phage to E. coli so that some samples having more phage would be expected to be infected quickly while others would take longer and show stronger dynamics.

You may like

Because the two experiments couldn’t run in perfect parallel, the team recorded the exact incubation times on the ISS and then matched them on Earth afterward, a common workaround for many ISS biological experiments.

Microgravity slows down interactions

Under typical Earth lab conditions, the T7 phages can infect and kill E. coli cells in well under an hour, given the life cycle of the phage. But in the system’s completely sealed and shake-free setup, which mimicked the conditions of microgravity, the system moved more slowly overall.

On Earth, the control group showed a surge in bacterial infections between two and four hours, but in microgravity, the surge didn’t appear at any of the shorter incubation periods, suggesting that the phages’ infection process had slowed down. Yet, the longer incubation vials told a different story, as after 23 days in orbit, the infection process was successful with fewer E. coli found in the vials.

So why do the researchers think the slowdown happened?

“We hypothesize that reduced fluid mixing in microgravity, because there’s no gravity-driven convection, lowers the encounter rate between phage and bacteria, and that microgravity-induced stress on the host may alter receptor expression or intracellular processes, further slowing productive infection,” Huss added.

In other words, in microgravity, phages and bacteria don’t bump into each other as often and the bacteria may have evolved to be more resistant to phage attacks that make infection harder, so the entire cycle starts later than it does on Earth.

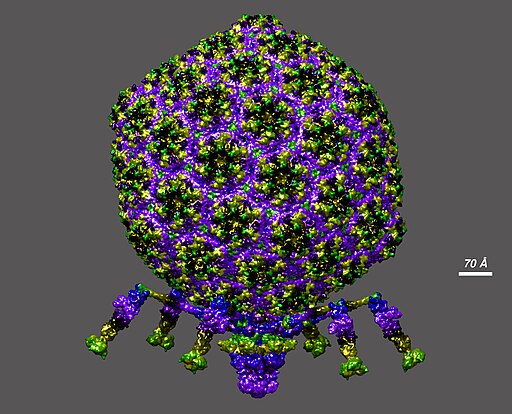

A structural model of bacteriophage T7 at atomic scale. (Image credit: Dr. Victor Padilla-Sanchez, PhD, CC BY-SA 4.0)Microgravity mutations

After 23 days, the team analyzed the genetic make-up of the phages and saw mutations across its genome, but with microgravity-specific mutations, especially in genes tied to structure and host interaction. These mutations changed how the phage infects the bacteria.

“To me one of the most striking findings was not just that mutations appeared across the phage genome, but that microgravity pushed evolution into corners of the phage we still don’t fully understand,” Huss said.

Based on their findings, microgravity may not just change how fast infection happens but also which of a virus’s genes matter most when it comes to successfully infecting a bacterial host.

“We’re just beginning to scratch the surface,” Dr. Srivatsan Raman of the University of Wisconsin-Madison, another lead author on the study, told Space.com. “We just have to do more experiments with more complex conditions.”

The phages weren’t the only ones to change, as the bacteria seemed to evolve too. The E. coli exposed to the phages accumulated many more mutations than bacteria without phage threats, consistent with selection pressure that drives evolutionary arms races.

Some of the most notable changes hit genes linked to the outer membranes, potentially altering phage attachment while helping bacteria survive stress.

“Microgravity doesn’t just slow things down, it qualitatively reshapes phage–host coevolution, from infection dynamics to the specific genes and mutations that matter,” Huss noted.

Microgravity as a way forward for Earth-based medicine?

Using a technique called deep mutational scanning, the team scanned for over 1,600 mutation variants in the phage genome, finding that the “winning” mutations in microgravity differed sharply from those on Earth.

“Our results support microgravity as a distinct selection environment that reveals different parts of the fitness landscape than we can capture terrestrially,” said Huss.

The researchers used these mutations to create altered phages which they tested on uropathogenic E. coli — strains of E. coli associated with urinary tract infections — that were more resistant to the T7 phages’ attacks. The results showed that these altered viruses could kill the resistant bacteria.

“What we found in the study was that phage mutants that were enriched in microgravity could treat uropathic bacteria and kill them. So, which tells us that there’s something about the microgravity condition that makes it relevant for treating pathogens on Earth,” Raman said.

This has big implications for possible future treatments of bacterial diseases here on Earth, from salmonella poisoning to pneumonia to sepsis. But conducting the further testing required to get there may be tricky.

“Running these experiments on the ISS, that’s not trivial,” Raman added. “I mean, that takes years of planning, and there’s just a lot of logistical challenges to get through. To run these experiments, pulling them off in a routine manner would actually be a little challenging to execute.”

An image of E. coli bacteria under the microscope. (Image credit: NIAID)What about the future of spaceflight?

Zooming from the microscopic to the macroscopic, these results suggest that space microbes won’t stay static but instead adapt and evolve in microgravity-specific ways.

“What our data makes clear is that microbes can adapt rapidly and in unexpected ways in microgravity,” Huss added. “In principle, those same pressures could enrich traits we worry about on Earth, including drug resistance or altered virulence. This is a plausible evolutionary trajectory that future experiments should actively test by monitoring antibiotic susceptibility, stress responses, and competitive interactions over time.”

Could these adaptations truly be a threat for humans on long-term space missions? Possibly, but for Raman, more testing is needed before that conclusion could be reached.

“Pathogens evolve all the time,” Raman said. “I think we ought to do more studies to see if bacteria can evolve towards mutations that might make them more pathogenic under microgravity conditions. Those are not experiments that we’ve actually done in this study.

“But bacteria are very resilient and they evolve all the time. So I wouldn’t rule out the possibility, but again, one has to do these rigorous experiments to ask: can a bacteria become a pathogen under ISS conditions?”

One such area of future space research could be looking at the human microbiome, as it’s still not well understood how the microbiome evolves in the conditions of space.

For humans on Earth, the results of this study are more positive, as microgravity could help scientists to develop phages that can kill off more resistant bacteria.

“The real power of these space-derived fitness landscapes is that they don’t stand alone. They can be merged with the rich terrestrial datasets we already have to sharpen engineering strategies for therapeutic use cases. That’s arguably the most immediately actionable takeaway,” said Huss.