Most supermassive black holes sit in the “downtown” of a galaxy, and they grow by pulling in gas and dust. When that material falls inward, it heats up and glows so brightly that we can detect it across vast distances.

As more data from NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) become public, astronomers search its archives for overlooked cosmic oddities.

In the COSMOS-Web survey, one system looked like a sideways figure-eight, and it raised a question: What is powering its glow?

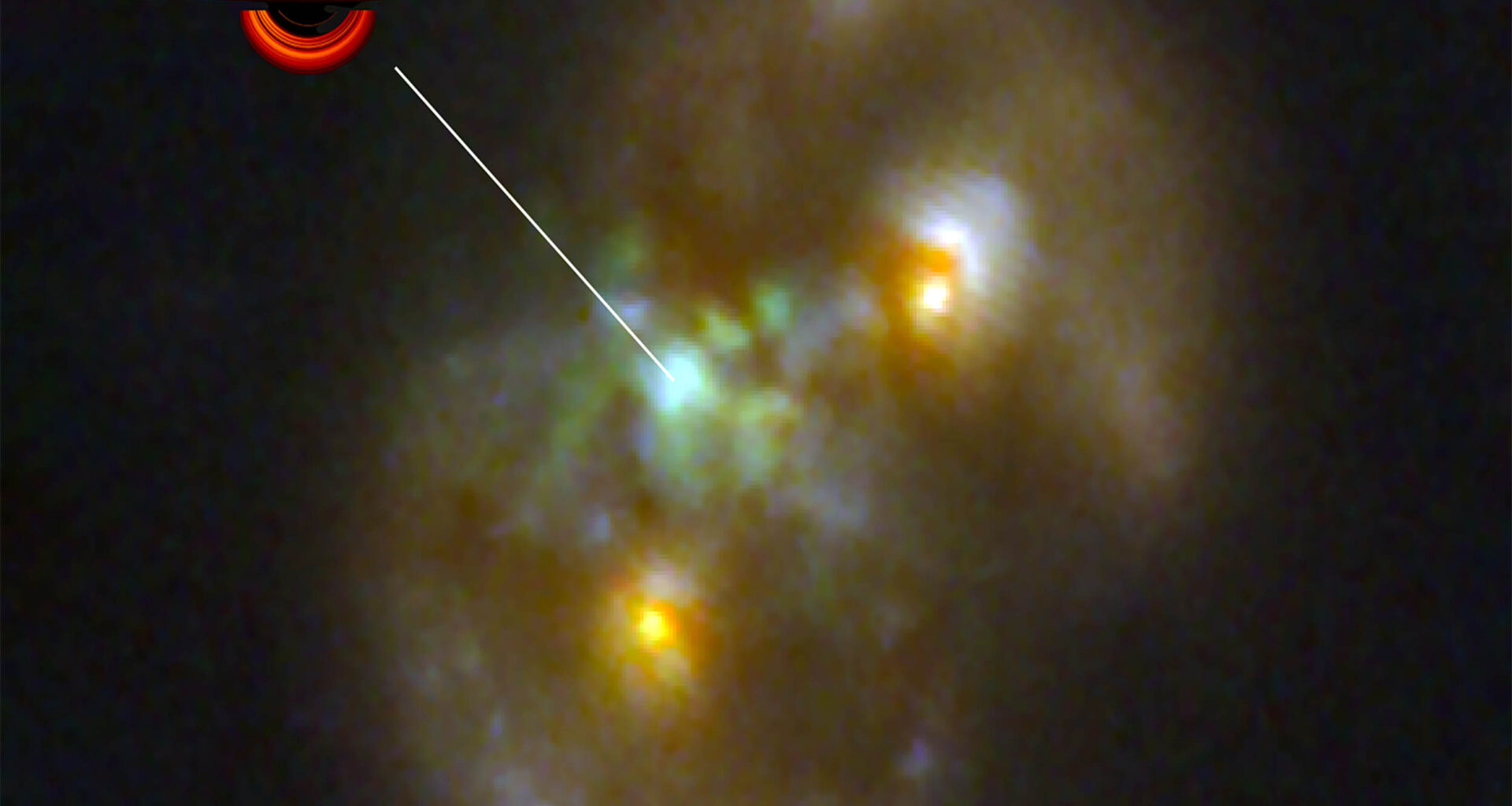

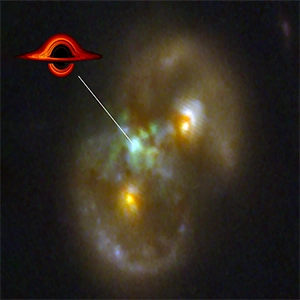

Webb’s view of Infinity galaxy

Pieter van Dokkum of Yale University and Gabriel Brammer of the University of Copenhagen found the object in the COSMOS field and nicknamed it the “Infinity Galaxy” because it appears to sit between two galaxy cores.

Webb’s infrared view shows two compact, reddish “bulges” separated by about 10 kiloparsecs (roughly 33,000 light-years), and each is surrounded by a bright ring or shell of stars.

Each bulge contains about 100 billion Suns’ worth of stars. The COSMOS region also has a deep archive of older observations, so the team could check the system using more than one telescope.

The “Infinity Galaxy” as captured by the James Webb Space Telescope, is the result of a cosmic collision between two galaxies, forming a shape that resembles the infinity symbol. This merger gave rise to a newborn supermassive black hole. Credit: James Webb Space Telescope and NASA. Click image to enlarge.Evidence of an active black hole

The “Infinity Galaxy” as captured by the James Webb Space Telescope, is the result of a cosmic collision between two galaxies, forming a shape that resembles the infinity symbol. This merger gave rise to a newborn supermassive black hole. Credit: James Webb Space Telescope and NASA. Click image to enlarge.Evidence of an active black hole

The researchers brought in three key kinds of “detective evidence”: spectroscopy (splitting light into a spectrum to identify elements) from the Keck telescope, radio observations from the Very Large Array, and X-ray observations from Chandra X-ray Observatory.

The Keck spectrum shows strong emission lines from highly ionized atoms, which usually means an intense energy source has stripped electrons from those atoms.

The spectrum looks like what astronomers call a narrow-line active galactic nucleus, a sign of an actively feeding supermassive black hole.

The radio and X-ray data strengthened that case. A normal cluster of stars cannot easily explain bright, compact radio emission and strong X-ray output at the same location.

When the team compared the locations of the radio source, the X-ray source, and the high-ionization emission lines, all three lined up with the same messy central region.

That region was described as complex and stretched, with tendrils of emission, and it matched the radio source very well.

“Everything is unusual about this galaxy. Not only does it look very strange, but it also has this supermassive black hole that’s pulling a lot of material in,” Van Dokkum explained.

“The biggest surprise of all was that the black hole was not located inside either of the two nuclei but in the middle. We asked ourselves: How can we make sense of this?”

Hidden gas in the Infinity galaxy

One Webb filter, called F150W, can become extra bright if it detects specific glowing gas lines at the system’s redshift (how much its light is stretched by the expanding universe).

In this object, the F150W band includes bright hydrogen emission and nearby nitrogen and sulfur lines.

The team built a “continuum-subtracted” map by removing the regular starlight to isolate just the glow from the gas. That map shows extended ionized gas spread across the region between the two bulges.

They then measured the equivalent width (a standard way to compare a line’s strength to nearby light) to see how strong the emission lines are compared with the surrounding starlight.

Across the central gas structure, these emission lines reached hundreds to a couple of thousand angstroms in rest-frame equivalent width.

Many active galaxies have enough starlight to add “background light” and dilute those values, so the extreme numbers suggest lots of glowing gas with few stars mixed in.

“Finding a black hole that’s not in the nucleus of a massive galaxy is in itself unusual, but what’s even more unusual is the story of how it may have gotten there,” Van Dokkum noted.

“It likely didn’t just arrive there, but instead it formed there. And pretty recently. In other words, we think we’re witnessing the birth of a supermassive black hole – something that has never been seen before.”

Collision may explain black hole

The authors argue that a nearly head-on collision between two disk galaxies can create the ringed pattern, forming what astronomers call a collisional ring galaxy.

Stars mostly pass through, but gas clouds can collide, shock, and compress. As a result, the crash can pile gas into a dense, turbulent zone and leave a concentrated “leftover” gas structure near the impact site.

The study also considers other explanations. These include a third faint galaxy that hosts the black hole, a black hole kicked out after two black holes merged, or a black hole stripped from a smaller galaxy.

The authors argue those options don’t match Webb’s view cleanly: the central region doesn’t look like a normal small galaxy, and the huge equivalent width implies any “host” starlight would have to be unusually faint.

So they connect the system to the “direct collapse” concept, where gas becomes dense enough to collapse under its own gravity before it forms many ordinary stars (in other words, it may collapse into a black hole first).

Using the rings’ geometry and other clues about the system’s scale, the authors estimate that the collision happened around 50 million years ago.

They suggest that if a black hole started at a few hundred thousand solar masses, it could grow to around a million solar masses over that timescale if it fed efficiently.

The team calls it a “candidate direct-collapse black hole” and wants more detailed spectroscopy and simulations to test whether the gas can collapse into a seed black hole (a small starting black hole) instead of mostly forming stars.

The full study was published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–