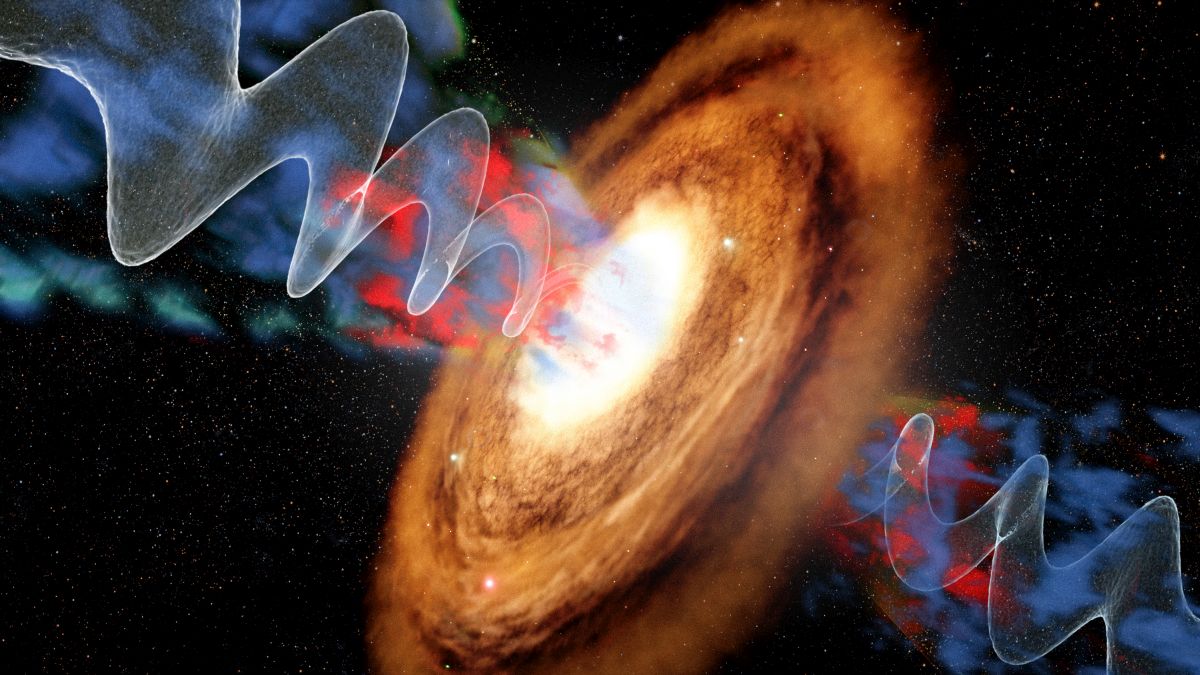

A nearby galaxy has been caught draining itself of star-forming fuel, with vast streams of superheated material twisting away from the supermassive black hole at its core.

The galaxy, called VV 340a, offers us a rare glimpse into one way black holes curtail star formation in their host galaxy, from a relatively close vantage point of around 500 million light-years. VV 340a’s black hole is ejecting so much material that star-formation rates are likely being affected, researchers say.

“To our knowledge, this is the first time we have seen a kiloparsec, or galactic-scale, precessing radio jet driving a massive coronal gas outflow,” says astrophysicist Justin Kader of the University of California, Irvine.

“What it really is doing is significantly limiting the process of star formation in the galaxy by heating and removing star-forming gas.”

Related: Largest Black Hole Jets Ever Seen Create a Galactic Structure That Will Blow Your Mind

Although supermassive black holes are thought to be a vital ingredient in galaxy formation, they can also eject so much radiation that they ‘starve’ galaxies of the material needed to form new stars. If a galaxy becomes inactive, it’s not necessarily a permanent state, but it does signal that the wild, blazing, youthful eons are over.

Black holes can shut down star formation via a few different mechanisms, collectively known as ‘feedback’, which arise from black hole activity: powerful jets, radiation pressure, and black hole winds that whip up as the black hole scarfs down matter at a tremendous rate.

Jets are colossal structures that erupt from the poles of an actively feeding black hole. The black hole devours clouds of gas and dust that spiral into a disk around the ravenous object, although not all of that material ends up beyond the event horizon.

Astronomers aren’t entirely clear on the exact particulars, but they believe that some of the material is diverted from the inner edge of the disk and accelerated along the black hole’s magnetic field lines outside the event horizon. When it reaches the poles, the material is launched into space at tremendous speeds, sometimes a significant fraction of the speed of light.

frameborder=”0″ allow=”accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share” referrerpolicy=”strict-origin-when-cross-origin” allowfullscreen>

frameborder=”0″ allow=”accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share” referrerpolicy=”strict-origin-when-cross-origin” allowfullscreen>

Over time, this expulsion can create structures (jets) that extend for millions of light-years. The jets from VV 340a haven’t been traveling through space for that long; they extend about 20,000 light-years in each direction from the black hole, filled with shock-heated, ionized gas.

However, they’re the largest and most extended jets of shock-heated, highly ionized coronal gas – material heated to temperatures comparable to the Sun’s outer atmosphere – ever discovered.

“In other galaxies, this type of highly energized gas is almost always confined to several tens of parsecs from a galaxy’s black hole, and our discovery exceeds what is typically seen by a factor of 30 or more,” Kader says.

Here’s the interesting thing: The jets from VV 340a are large, but not particularly powerful, as far as astrophysical jets go.

Even so, they seems to be funneling away about 19.4 Suns’ worth of mass from the galaxy every year. To put that in perspective, the Milky Way makes up to around 3.3 Suns’ worth of new stars every year.

The shape of VV 340a’s bidirectional jet may have something to do with how efficiently the star-forming material is being evacuated from the galaxy. The jet precesses: its rotation wobbles a bit, like a spinning sprinkler. This means that the jet is shaped more like a helix than a straight line.

The researchers think that, as they spew forth, VV 340a’s helical jets couple with the gas in the galaxy and drag it along, heating it to coronal temperatures at distances from the black hole that astronomers have never seen before.

What’s more, helical precessing jets are usually only seen in older galaxies. VV 340a is relatively young and in the process of a merger with another galaxy. The discovery suggests that even young-looking galaxies can have episodes of feedback in ways we don’t expect.

Because VV 340a is merging with another galaxy, any damping effect on its star formation rate is unlikely to last long. Galaxy mergers often produce a period of increased star formation as star-forming material in each galaxy is shocked and compressed, producing the perfect conditions for a stellar baby boom.

“We’re only beginning to understand how common this kind of activity may be,” says astronomer Vivian U of Caltech.

“We are excited to continue exploring such never-before-seen phenomena at different physical scales of galaxies using observations from these state-of-the-art tools,” such as JWST, she adds.

“We can’t wait to see what else we will find.”

The discovery has been detailed in Science.