Art

Hilda Palafox, Mural for Urvanity Art 2019, Madrid. Courtesy of the artist.

One of Hilda Palafox’s early murals, painted in 2019 on the side of a residential building above a café in Madrid’s La Latina neighborhood, depicts two elongated female figures standing back-to-back, their bodies interlocked as they balance a shallow bowl of fruit overhead. The figures’ simplified silhouettes and interaction with a man-made object anticipate a visual language that would come to define her work—one rooted in balance, attentiveness, and feminine interdependence.

Living and working in Mexico City, Palafox has been shaped by the city’s modernist architecture and monumental public art. “In Mexico, muralism has a deep history,” Palafox said in an interview with Artsy. “The Mexican muralism movement was about education for everyone, about beauty in daily life.”

Portrait of Hilda Palafox by Angela Simi. Courtesy of the artist.

Now, Palafox’s practice, with its muralist inspirations, has gained increasing international visibility. She has exhibited widely across Mexico and the United States as well as further afield, and is represented by Proyectos Monclova. When we spoke, the artist was preparing for a New York solo exhibition, “De Tierra y Susurros (Of Soil and Whispers),” which opened January 9th at Sean Kelly Gallery. “I’m nervous—in a good way,” she admitted with a smile. The exhibition brings together a new body of paintings and works on paper with “Portales,” a series of stone reliefs carved from cantera—a lightweight volcanic stone long used in Mexican architecture. Together, these works shift the site of monumentality from scale to sensation. “My work is always an invitation to look inside,” she said. “To be more gentle with what’s going on outside.”

Emerging in the early 20th century, Mexican muralism sought to make art accessible beyond institutional spaces, using public walls to address history, social struggle, and collective memory. Palafox cites figures such as José Vasconcelos, Jorge González Camarena, Juan O’Gorman, and, in particular, Carlos Mérida, whose abstraction of the human figure into simple, modular forms expanded muralism beyond narrative realism toward symbolic geometry.

Palafox has been drawing for as long as she can remember. But it wasn’t until 2016, when she began painting murals, that her practice fully opened up. “I always loved making things with my hands,” she said, reflecting on her childhood growing up in Mexico City. “In high school, I had many friends who were into art, but I didn’t know what it meant to be a painter. I didn’t have that contemporary view yet.”

She went on to study design at the Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes (INBA), drawn to its tactile, hands-on approach, where graphic, industrial, and textile design were all taught together. After graduating, Palafox worked briefly in advertising before turning to illustration, a shift that brought her closer to storytelling and image-making.

For Palafox, mural painting offered something illustration could not: physicality, scale, and a direct relationship with public space. “My illustration work was more alone in the studio,” she said. “When you work on murals, you’re outside, among people, using your whole body.”

Meanwhile in the studio, Palafox gravitated toward larger canvases, translating the physicality of mural-making into painting. What began as a graphic style gradually became more fluid and layered. The transition from acrylics to oil opened, as she put it, “a whole new universe.” Color deepened to earthen tones and subtle contrasts, edges softened, and surfaces gained texture and density. “When you hear ‘nature,’ most people think of green,” she noted, “but I wanted to work with soil and earthy tones. There’s heat in everything now.”

Her current studio, a small apartment she rents from her sister in Mexico City’s Narvarte neighborhood, is just a short walk from her home. A jacaranda tree blooms outside the window, bringing a sense of serenity into the space. “At some point, I would love to have a big space for more explosive creation,” Palafox admitted. “For now, it works.”

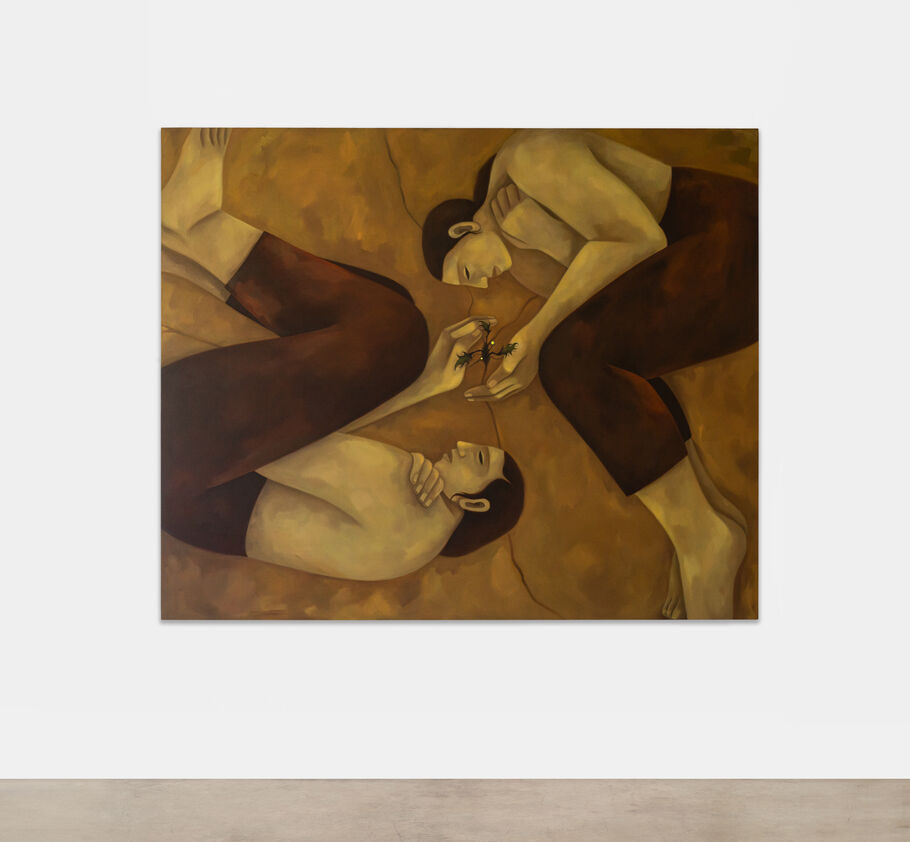

In the painting Susurros I (2025), two women lie on cracked ground, their ears pressed to the earth, figures and landscape melding into a shared, heat-worn terrain, as a small plant grows between their joined hands. The composition privileges listening over action, framing attention as a form of care. “It’s not only about life or procreation,” Palafox said. “It’s about knowledge—about pulling something from within.”

That language of touch is also visible in Ritual a las faldas de un volcán (2025), a large-scale composition depicting multiple figures gathered at the base of a smoldering volcano, moving together in a circular dance. “Las faldas” refers both to a skirt and to the lower slopes of a volcano, introducing layered symbolism: The volcano is a site of danger and fertility, destruction and renewal. “The ground of the volcano explodes,” she noted, “and the earth where the lava goes is very fertile. A new beginning.” The work signals an expansion of her practice, as Palafox embraces greater material density and painterly flow.

“I want people to pause, to listen,” Palafox said. “To see that we are part of something living.” In “De Tierra y Susurros,” that invitation feels especially resonant. Across painting, paper, and stone, her figures merge with land—rooted, patient and quietly attentive. The works linger, somewhere between soil and skin, asking that you stay with them a little while.