Some buildings are born with a systemic vocation. They aspire to be more than just containers for human activity and behave like three-dimensional diagrams of the world, ideological machines disguised as concrete. El Helicoide was born with precisely that ambition, perhaps too much so.

Venezuela in the 1950s. With dictator Marcos Pérez Jiménez at the helm, the country was overflowing with gasoline, dollars, and a very specific kind of civic silence that could be mistaken for political stability. Oil permeated everything. There was money, there was speed, and with both, an almost sweaty faith in the idea that the future was guaranteed and that any attempt at objection would be drowned out by pressing the gas pedal. Literally.

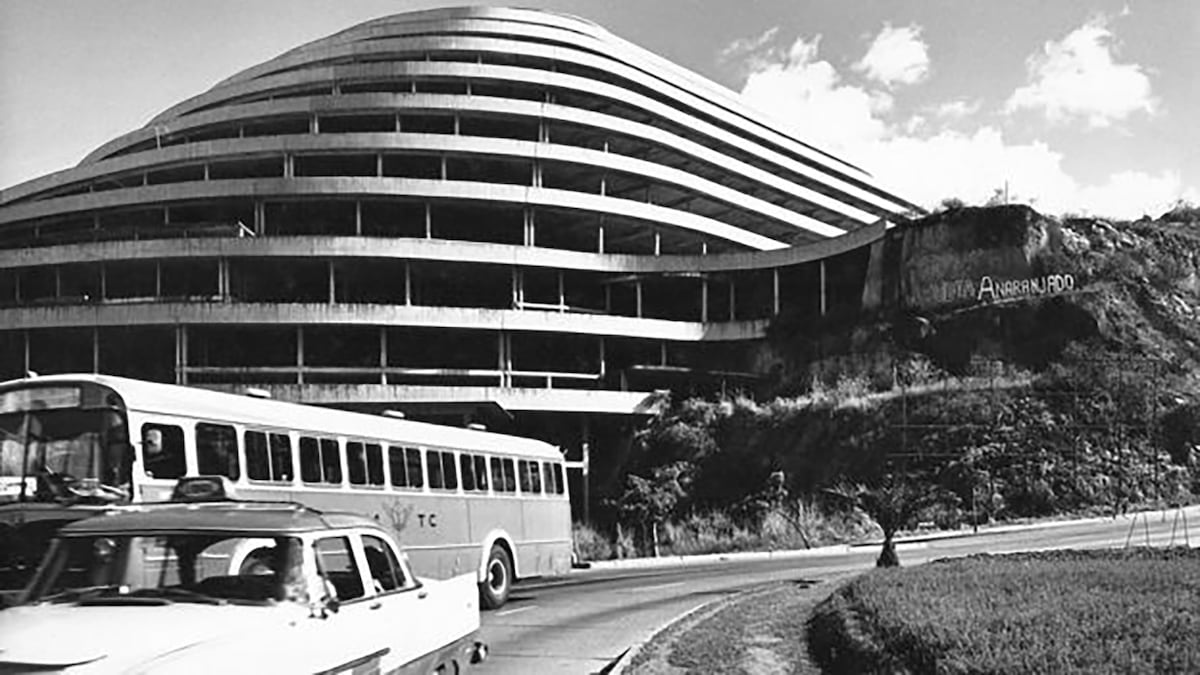

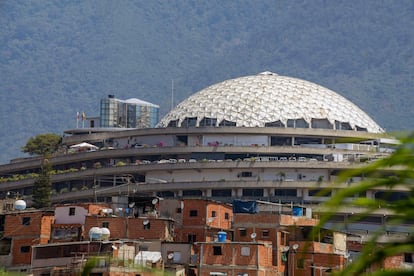

El Helicoide, with its impeccably designed ramp and its still-shining dome, in 2021.Alamy Stock Photo

El Helicoide, with its impeccably designed ramp and its still-shining dome, in 2021.Alamy Stock Photo

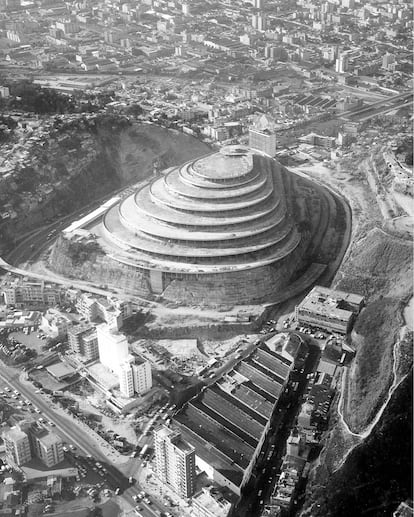

This economic, political — and moral — ecosystem was condensed into a project as simple in its gesture as it was excessive in its consequences. A shopping mall that could only be traversed by car, without getting out of the vehicle and without walking. Without abandoning the steering wheel, lest progress escape through the back door. Thus, El Helicoide was conceived as a single, continuous movement. A ramp. A spiral path that encircled the Tarpeian Rock and rose above Caracas, transforming consumption into a journey and the incline into a substitute for urban strolling.

Designed by Jorge Romero Gutiérrez, Pedro Neuberger, and Dirk Bornhorst, the project included hundreds of shops, eight cinemas, a five-star hotel, a private club, a performance hall, and even a helipad, in case the oil boom reached such a point that customers arrived directly from the skies. Crowning it all was a geodesic dome designed to reflect the tropical light and return it to the city, transformed into an abstract symbol. Four kilometers (2.5 miles) of asphalt spiraled around the hillside, where cars would stop in front of every shop window, every cinema, every restaurant, transforming the act of shopping into a perfectly calibrated mechanical choreography. El Helicoide was more than just a building. It was a compact symbol in which form was the message, because the spiral was not just a path, it was a gesture that promised perpetual ascent, frictionless circulation toward continuous progress that, at that time, seemed to have no expiration date. So much so that its design circled the globe even before the building was fully constructed. It was exhibited at MoMA, Pablo Neruda called it a “concrete rose,” and Salvador Dalí offered to decorate its interiors. Everything fit the narrative.

In 1956, studies of El Helicoide began to make the idea conceived by the architect Jorge Romero Gutiérrez a reality.

In 1956, studies of El Helicoide began to make the idea conceived by the architect Jorge Romero Gutiérrez a reality. Work at El Helicoide in 1956.

Work at El Helicoide in 1956.

In that state of architectural celebration, construction began in 1956, observed with proud awe by the white elites who had envisioned it and with a mixture of intimacy and infinite distance by the Black children of the nearby neighborhoods, who would probably never be able to travel through it. Because to inhabit El Helicoide required gasoline and a robust faith in the eternity of the regime. But eternity endured less than the oil.

In 1958, the Pérez Jiménez dictatorship fell, and the building was caught in the ebb and flow of change. Funds froze. Lawsuits piled up. The company went bankrupt. The imported elevators disappeared. The interior was left exposed to rain, looting, and slow deterioration. An attempt was made to resume construction. Some sections were completed, including the dome, but El Helicoide never became what it was intended to be. For years it remained unfinished, too grand to ignore and too laden with symbolism to complete without discomfort.

View of the Cota 905 neighborhood and El Helicoide, in Caracas (2022).Alamy Stock Photo

View of the Cota 905 neighborhood and El Helicoide, in Caracas (2022).Alamy Stock Photo

In the late 1970s, thousands of homeless people occupied the structure. The ramps designed for cars were filled with mattresses, makeshift stoves set up halfway up the slope, and clothes hanging where once there had only been structural calculations. El Helicoide became an informal city embedded in a futuristic engineering work, a layering of times and uses that ended in evictions and returned the building to a new state of expectant emptiness.

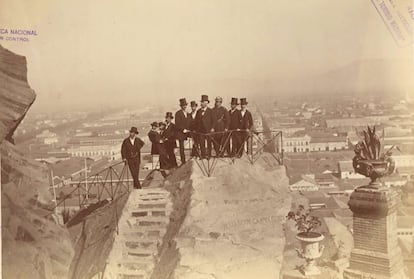

The Tarpeian Rock, where El Helicoide was built, in 1874. Photo by Pedro Emilio Garraud.

The Tarpeian Rock, where El Helicoide was built, in 1874. Photo by Pedro Emilio Garraud.

But another transformation was yet to come. In an unintentional and sinister homage to the hill’s name — the Tarpeian Rock in Rome was the place from which traitors and thieves were thrown to their deaths — the building’s function changed once again. Starting in 1982, the state began to gradually establish itself within its walls. First, administrative offices. Then, security agencies. In 1984, the DISIP (General Directorate of Intelligence and Prevention Services) used it as its headquarters and as a detention center. In 1992, during Hugo Chávez’s second coup attempt, an OV-10 Bronco from the rebel Air Force bombed the building, and the resulting anti-aircraft fire destroyed part of the facilities. But El Helicoide was already too important to abandon again, so it was rebuilt and, as of 2010, under the Chavista regime, it became a detention center for SEBIN, the Bolivarian National Intelligence Service. And SEBIN transformed a circulation device into an internal control mechanism. Offices were converted into cells, bathrooms sealed off for confinement, and curved corridors integrated into a monitored circuit that erased any stable spatial reference. The prisoners gave names to these former stores. Little Hell. The Guarimbero. Guantánamo. The Little Tiger. The Cockroach. The Fishbowl. A tropical bestiary, surreal and terrifying all at once. Because these names, however close they may be to verbal folklore, designate places where organizations like Human Rights Watch have denounced torture, extreme overcrowding, electrocutions, immersion in feces, and sexual abuse.

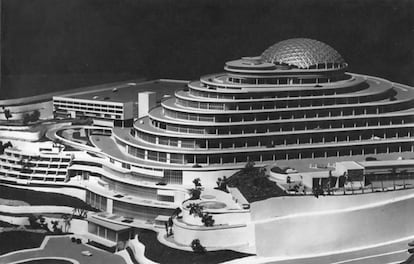

A model of El Helicoide.Cámara de Comercio, Industria y Servicios de Caracas

A model of El Helicoide.Cámara de Comercio, Industria y Servicios de Caracas

To this day, El Helicoide still stands, towering over Caracas. The White House has stated that Delcy Rodríguez plans to dismantle the detention center, but for now, the building’s future remains uncertain, true to form.

Seen in photographs, with its impeccably designed ramp and its still-gleaming dome, El Helicoide, for me — someone who has always believed in the capacity of built spaces to improve life — leads to a chilling reflection: that architecture — or rather, the humans who use it — has the capacity to adapt to anything. To anything. That a project conceived under a dictatorship as a delirious promise of the future can end up, with hardly any modifications, as a political prison under another dictatorship. And that all of this — the oil, the cars, the ramp, the asphalt, the luxury for a few and the poverty for many, the looting, the arrests, the bombings, the cells, and the torture — functions, whether we like it or not, as a strange and brutal summary of the last 70 years of Venezuelan history.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition