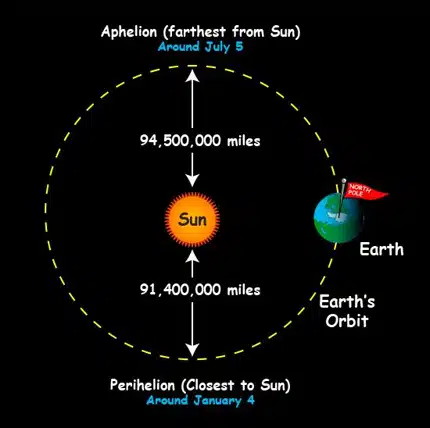

Each year, Earth reaches its closest point to the sun in early January, a moment called perihelion. In 2026, this occurred on January 3 at 12:15 p.m. EST, when Earth was about 91.4 million miles from the sun. The event may sound dramatic, but its impact on our seasons is practically nonexistent.

Earth’s journey around the sun is not a perfect circle. Instead, it follows a slightly elliptical orbit, bringing the planet marginally closer or farther from the sun throughout the year. While that distance changes by around 3%, scientists emphasize it doesn’t affect global temperatures. As reported by Space.com, the tilt of Earth’s axis, not its proximity to the sun, is what governs the rhythm of seasons.

Perihelion, Simply Explained

The term “perihelion” comes from the Greek peri (around) and helios (sun) and refers to the closest orbital point of a celestial body to the sun. As EarthSky reports, Earth’s perihelion in 2026 occurred at a distance of 147,099,894 kilometers. That’s about 5 million kilometers closer than at aphelion, the farthest point from the sun, which happens in early July.

Earth is closest to the Sun in January and farthest in July. Credit: NASA

Earth is closest to the Sun in January and farthest in July. Credit: NASA

Despite the significant-sounding gap, this variation represents only about 3% of the average Earth-sun distance, or one astronomical unit (AU), defined as roughly 149.6 million kilometers. The small eccentricity of Earth’s orbit ensures that solar energy received at perihelion versus aphelion remains nearly the same.

“The effect of this seasonal variation on the planet’s climate is negligible,” according to data cited from Space.com.

However, perihelion becomes a lot more meaningful in objects with highly elliptical orbits, especially comets or spacecraft like NASA’s Parker Solar Probe.

A Turning Point In Planetary Motion

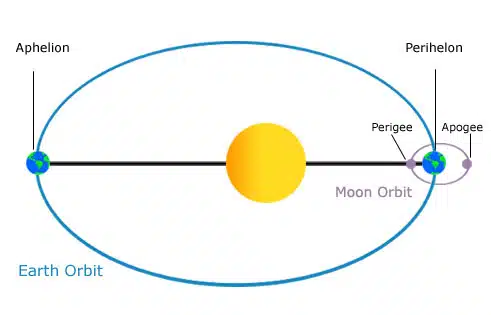

Around 1604, astronomer Johannes Kepler formulated his first law of planetary motion, demonstrating that planets move in elliptical paths with the sun at one focus of the ellipse. His conclusions were based on precise observations of Mars’s orbit.

A visual showing Earth’s oval-shaped path around the Sun. Credit: NOAA

A visual showing Earth’s oval-shaped path around the Sun. Credit: NOAA

Later, variations in solar timing puzzled early astronomers. As noted by Edward Bloomer of the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, medieval scholars noticed that solar days didn’t align perfectly with ideal timekeeping.

“They were already talking about the difference between the solar day and the ideal day, the average value of that,” he explained. “Things were running behind and ahead, which, as we later learned, is because of the changes of the speed at which Earth orbits the sun due to the elliptical nature of its orbit.”

Another observational tool, the analemma, a yearlong plot of the solar body’s position at the same time and place, illustrated these orbital quirks. Its figure-eight shape helped early observers infer orbital eccentricity and identify perihelion.

Perihelion: Mercury, Mars, and Comets

All planets in the solar system experience perihelion, though with varying impact. Venus and Neptune have nearly circular orbits, while Mercury, closest to the sun, has the most eccentric planetary orbit. According to figures from the Royal Greenwich Observatory, Mercury’s perihelion-aphelion difference is about 0.17 AU, a sizable swing for a planet averaging just 0.39 AU from the sun.

One of the most significant mysteries involving perihelion came from Mercury’s orbital precession. Newtonian physics couldn’t fully account for the small but measurable drift in its perihelion over time, about 43 arcseconds per century more than expected. The issue baffled astronomers until Albert Einstein’s general relativity explained it. “It was one of the three big tests of general relativity,” Bloomer noted.

Beyond planets, comets and asteroids experience much more dramatic perihelions due to their high orbital eccentricities. As the same source pointed out, their orbits can change significantly from pass to pass, sometimes even ejecting them from the solar system altogether due to gravitational interactions with massive planets like Jupiter.