A brief look at a quiet stretch of sky by the MeerKAT radio telescope revealed dozens of unseen galaxies, each carrying the raw material needed to keep making stars.

The findings show how much of the nearby universe can still hide in plain sight, even in short observation windows.

In less than three hours, South Africa’s MeerKAT radio telescope detected 49 previously unknown, gas-rich galaxies by tracing the hydrogen gas that fuels star formation and links neighboring systems.

That observation was originally planned to examine a single radio galaxy, but the same data quietly exposed dozens of additional systems.

The work was led by Dr. Marcin Glowacki at Curtin University in Western Australia. His research tracks how galaxies gain and lose gas over time, so unexpected signals became the focus.

Gas that makes stars

Star formation in galaxies rises with neutral hydrogen, hydrogen atoms with electrons still attached, as gas clouds cool and collapse into stars.

Because hydrogen sits between stars, mapping it shows where a galaxy can keep making stars over time.

Gas maps alone cannot show what sparked the collapse, so researchers still need starlight and dust measurements.

Radio telescopes trace hydrogen through a faint 8.3-inch radio signal from hydrogen atoms in cold space. The frequency changes with motion, so the spectrum shows each galaxy’s speed along our line of sight.

That signature travels through dust, which lets surveys spot gas-rich galaxies that optical images can miss.

Hunting galaxies with MeerKAT

MeerKAT is a radio telescope that sits 56 miles outside Carnarvon in South Africa, where dry air helps keep signals clean.

Its 64 receptors form an interferometer, a network of antennas that combines signals into images, across a 5-mile-span.

That layout gives sharp images and picks up weak emission, but the telescope still needs careful calibration to avoid false features.

Observations from many antennas arrive as streams of numbers, not pictures, so fast computing turns them into usable maps.

The Inter-university Institute for Data Intensive Astronomy (IDIA) built a data cube, a 3D map stacked by radio frequency.

Even with good code, weak signals can hide in noise, so IDIA teams still check results by eye.

Groups hidden in plain view

The team nicknamed the sample the 49ers after 1849 California gold rush miners, and many sit close together in the sky. A galaxy group can hold shared gas that drifts between members.

Crowded environments complicate measurements, because overlapping signals can blend and confuse which galaxy owns which gas.

One part of the 49ers shows three neighboring galaxies linked by hydrogen, with the gas stretching beyond their visible disks.

A tidal interaction, gravity from close passes that pulls material outward, can move gas into streams that another galaxy collects.

The map hints at one galaxy gaining fuel while companions lose it, but motion details require follow-up spectra.

Checking the starlight too

Optical and infrared surveys add missing context, because hydrogen alone cannot show how many stars each system already made.

Researchers estimated star formation rate, how much stellar mass forms each year, by combining ultraviolet and infrared light from each galaxy.

Those measurements help explain which 49ers still build stars and which ones mainly store gas without much activity.

Why short observations worked

A short observation can still reveal many galaxies when the telescope watches a wide patch with low receiver noise.

MeerKAT has a large field of view, the patch of sky a telescope images at once, so one pointing covers many targets.

Quick looks miss the faintest gas, so deeper follow-up is needed to measure total reservoirs and subtle bridges.

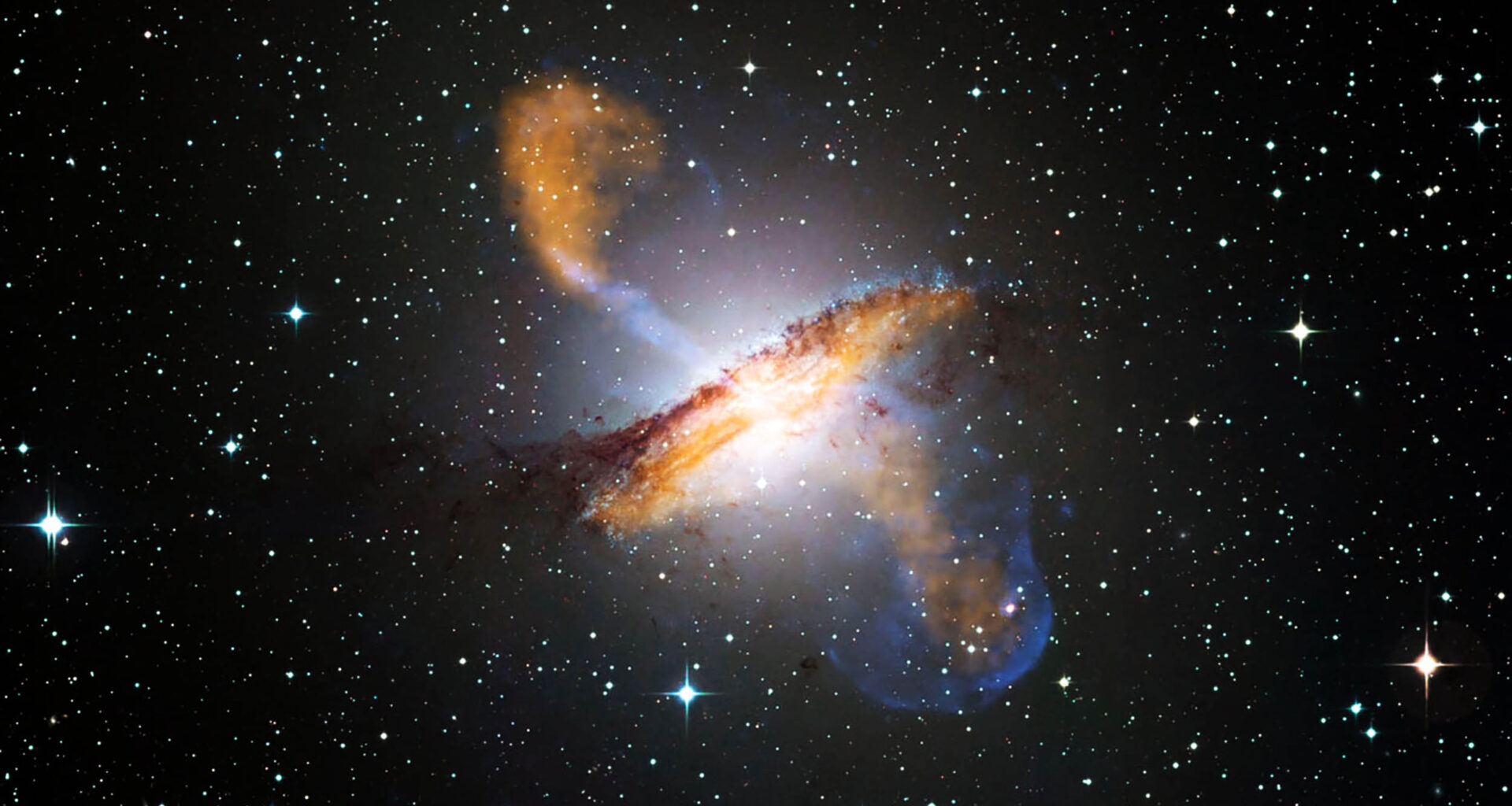

Centaurus A is a famous example of a relatively nearby radio galaxy. Inside the galaxy is a supermassive black hole which is generating the large jets which can be seen emerging perpendicular to the disc of the galaxy. Credit: ESO/WFI (Optical); MPIfR/ESO/APEX/A.Weiss et al. (Submillimetre); NASA/CXC/CfA/R.Kraft et al. (X-ray). Click image to enlarge.

Centaurus A is a famous example of a relatively nearby radio galaxy. Inside the galaxy is a supermassive black hole which is generating the large jets which can be seen emerging perpendicular to the disc of the galaxy. Credit: ESO/WFI (Optical); MPIfR/ESO/APEX/A.Weiss et al. (Submillimetre); NASA/CXC/CfA/R.Kraft et al. (X-ray). Click image to enlarge.

Software searches can scan cubes for galaxy-shaped signals, so researchers do not rely only on manual inspection.

A source finder, software that flags patterns matching real galaxies, can test several detection methods on the same data.

“I did not expect to find almost fifty new galaxies in such a short time,” said Dr. Glowacki.

Gas does not stay put, and when galaxies lose it to their surroundings, star making can slow down or stop.

Astronomers call this quenching, a slowdown in star making when gas runs low, and group environments often speed it up.

By measuring gas in many nearby systems at once, the 49ers show early warning signs, but they cannot show outcomes.

Open data helps science

Public archives hold many short projects that can yield extra science when someone looks again with new tools.

This pointing came from Open Time, telescope hours awarded through competitive review, and IDIA supports reuse across South African universities.

Open access invites more people to explore, but it also demands stable calibration records and clear links between files and results.

Lessons from the MeerKAT 49ers galaxies

Methods tested on the 49ers can scale up for larger surveys that need consistent results from machine searching.

Square Kilometre Array (SKA), a planned radio observatory made from linked antennas, will integrate MeerKAT into its Phase 1 system.

SKA surveys will push deeper, so teams need reliable pipelines and clear quality checks to avoid missing real galaxies.

Together, the 49ers demonstrate how quickly MeerKAT and modern data pipelines can map hydrogen in preparation for future SKA surveys.

“We hope to continue our studies and share even more discoveries of new gas-rich galaxies with the wider community soon,” said Glowacki.

Such follow-up work could expand the census of gas-rich systems and clarify how often galaxies exchange fuel in group environments.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–