For decades, wormholes have been hypothesized as mysterious tunnels that might let us cross galaxies or even time itself—but what if this picture is completely wrong? New study suggests that one of physics’ most famous “wormhole” ideas was never about travel at all.

Instead, it may be a hidden mirror of time itself. By revisiting a concept introduced by Albert Einstein nearly 90 years ago, the study authors have proposed a new way to reconcile gravity with quantum mechanics—and possibly even rethink what the Big Bang really was.

They have tried to combine Einstein’s theory of gravity, one of the deepest unsolved problems in physics. These two frameworks work extremely well on their own, yet they clash when pushed to extremes, such as inside black holes or at the birth of the universe.

The new study argues that the solution may have been hiding in plain sight, inside a long-misunderstood idea called the Einstein–Rosen bridge.

The curious case of the Einstein-Rosen bridge

In 1935, Albert Einstein and Nathan Rosen were not thinking about wormholes or cosmic highways. They were trying to fix a problem in how particles and gravity were described together.

Their “bridge” was a mathematical construction that linked two perfectly symmetrical copies of spacetime. It was designed to keep physical equations consistent, not to allow anything to pass through.

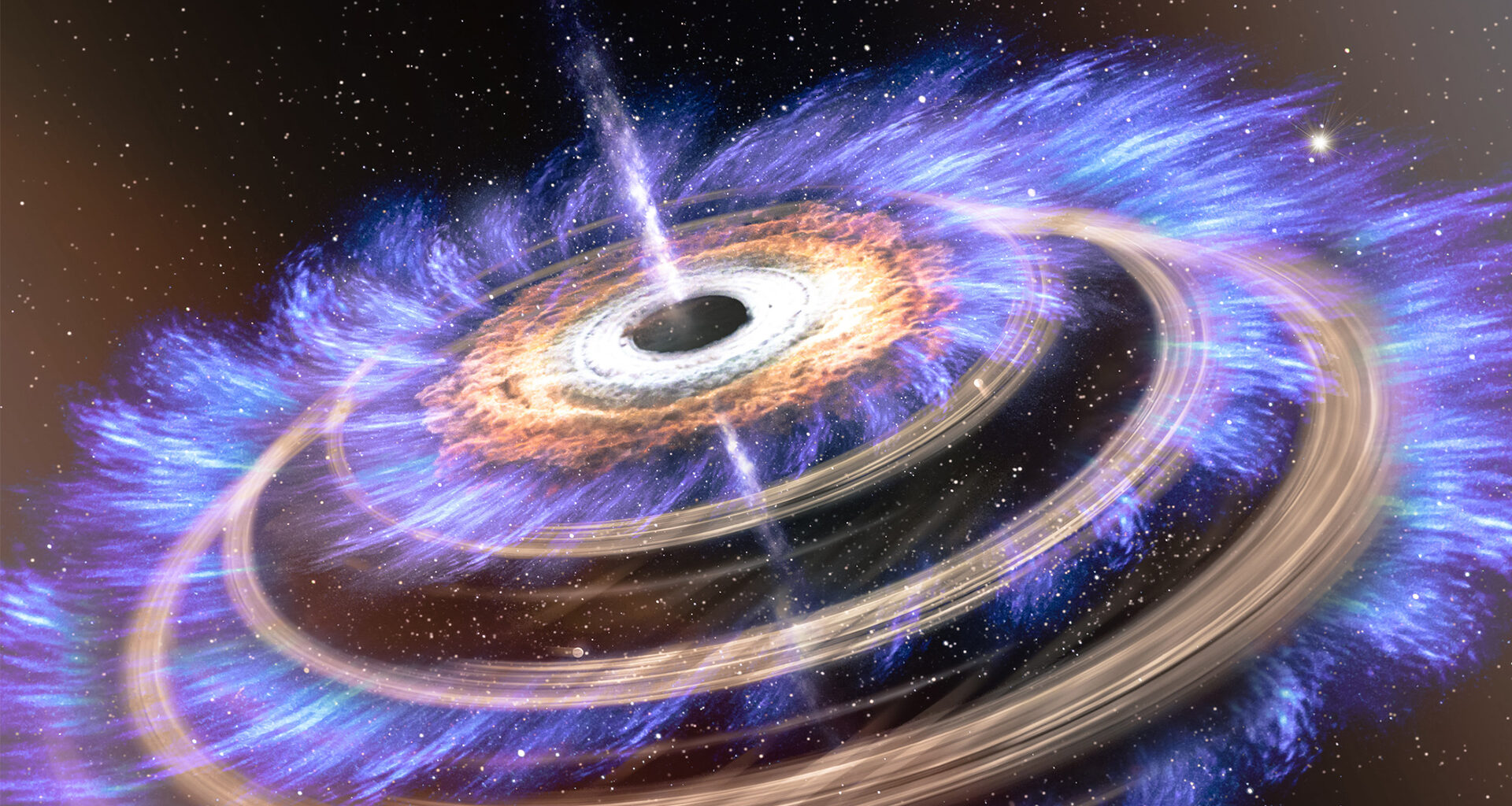

Decades later, physicists rebranded this idea as a wormhole, imagining it as a tunnel between distant regions of space. However, detailed calculations showed that such tunnels collapse too quickly to be crossed. So, within standard general relativity, Einstein–Rosen bridges are unstable and unobservable.

Despite this, the wormhole image took on a life of its own in popular culture and speculative physics. The new study goes back to the original problem Einstein and Rosen were tackling and reinterprets it using modern ideas from quantum theory—especially how time works at the smallest scales.

“This new understanding of the Einstein-Rosen (ER) bridges is not related to classical wormholes, it addresses the original ER puzzle and promises a unitary description of quantum field theory in curved spacetime (QFTCS),” the study authors note.

Wormholes are not tunnels

Most fundamental physical laws do not care whether time runs forward or backward. If you reverse time in the equations, they still work. This symmetry is usually ignored because, in everyday life, time clearly moves in one direction.

The researchers argue that at the microscopic level, especially near black holes or in extreme cosmic environments, this one-way view of time is incomplete. Instead, a full quantum description must include two components: one where time moves forward, and another where it moves backward in a mirror-like fashion.

The Einstein–Rosen bridge, in this view, is not a tunnel through space. It is a mathematical connection between these two opposite arrows of time. This reinterpretation has powerful consequences.

“These mathematical bridges not only retain the vision of ER, but also restore the unitarity in curved spacetime,” the study authors added.

For instance, one of the biggest puzzles in physics is the black hole information paradox. In the 1970s, Stephen Hawking showed that black holes emit radiation and can eventually evaporate, seemingly destroying all information about what fell into them. This violates a core rule of quantum mechanics, which says information must always be preserved.

The paradox arises because physicists usually describe black holes using only one direction of time. In the new framework, information is not destroyed at the event horizon. Instead, it continues evolving along the mirror, time-reversed component of the quantum state.

From our perspective, it disappears—but at the fundamental level, nothing is lost. The laws of quantum mechanics remain intact, without requiring exotic matter or radical changes to Einstein’s theory.

How this affects black holes, the Big Bang, and the universe itself

If this picture is correct, its implications go far beyond black holes. For instance, the same time-mirror structure could apply to the entire universe. The Big Bang may not have been the absolute beginning of time, but a quantum “bounce”—a transition between a contracting universe and an expanding one, each with opposite arrows of time.

In this scenario, our universe could be the interior of a black hole formed in a previous cosmos. As that region collapsed, quantum effects prevented a final singularity, causing spacetime to rebound and expand again.

Some traces of the pre-bounce universe—such as small black holes—might have survived and reappeared in our own cosmic expansion. Intriguingly, such relics could help explain part of what we currently call dark matter.

However, this idea remains theoretical. It does not predict sci-fi wormholes, faster-than-light travel, or time machines. Testing it will require new ways to connect quantum theory, cosmology, and observations of black holes and the early universe.

The researchers now aim to refine the mathematical framework and identify clearer observational signatures that could confirm—or falsify—the picture.

The study is published in the journal Classical and Quantum Gravity.