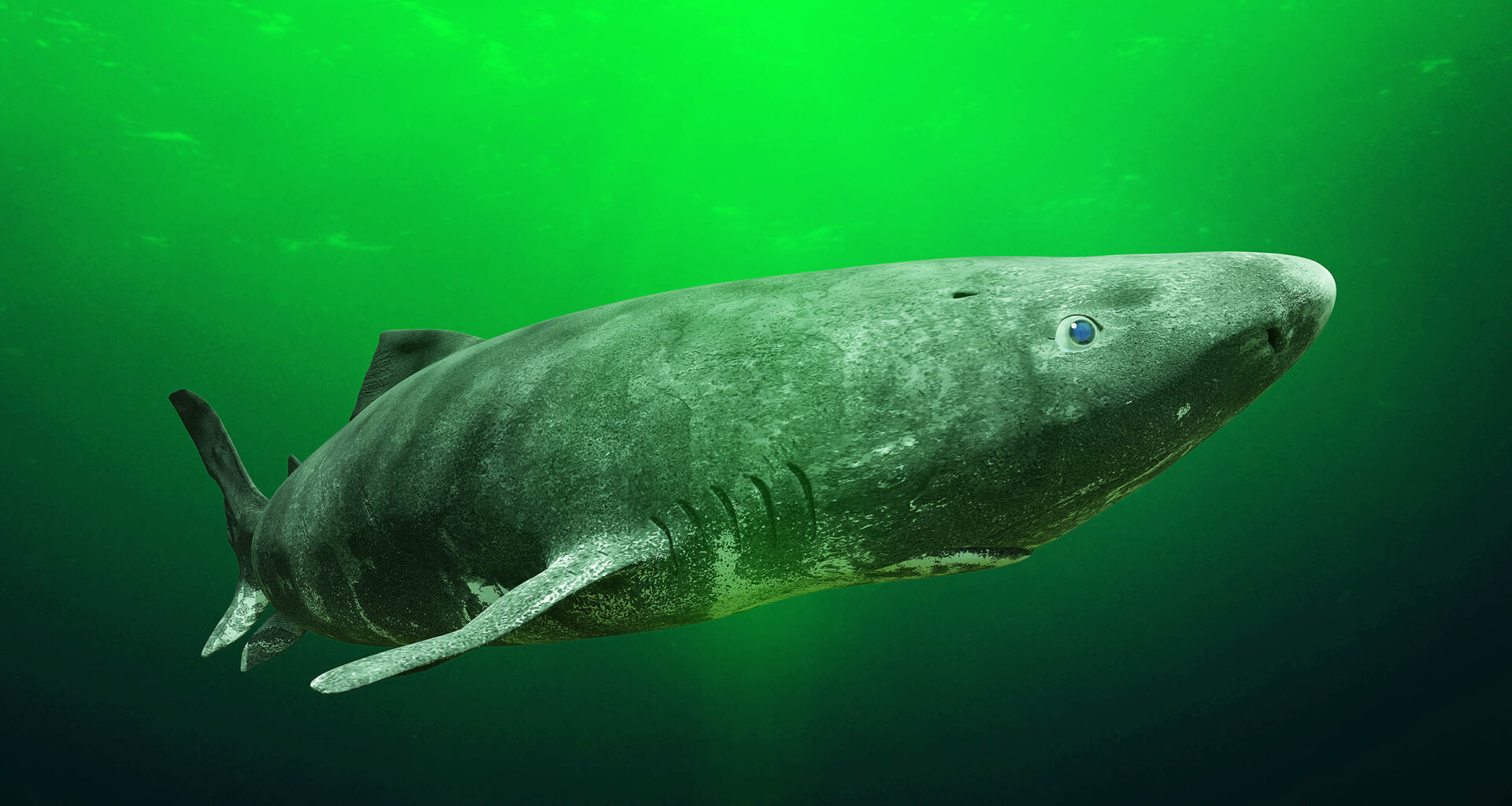

The Greenland shark is one of the most mysterious animals in the ocean. Living in cold, deep waters of the Arctic and North Atlantic, this slow-moving giant can live for centuries.

Some are believed to be over 400 years old, making it the longest-lived vertebrate known. A recent study takes a close look at one vital organ that must keep working for all those centuries: the heart.

Rather than finding a heart that avoids aging altogether, the researchers uncovered something more surprising.

The Greenland shark heart shows many classic signs of aging, yet it continues to function without obvious problems.

The research, led by teams from the Biology Laboratory at Scuola Normale Superiore, points to an unusual strategy for long life: not resistance to aging, but resilience in the face of it.

Aging hearts that still work

In most animals, including humans, aging hearts undergo structural changes that often lead to disease. One common change is fibrosis, where excess collagen builds up in heart tissue.

This stiffens the heart and reduces its ability to pump blood effectively. Over time, fibrosis raises the risk of heart failure and rhythm problems.

When scientists examined heart tissue from Greenland sharks, they found extensive fibrosis throughout the ventricle. Both the compact outer layer and the spongy inner layer of the heart were affected.

This pattern appeared in males and females alike. Under the microscope, collagen surrounded blood vessels and filled spaces between heart muscle cells.

Healthy sharks after centuries

What makes this finding remarkable is that the sharks appeared healthy at the time they were caught.

Their hearts showed no signs of failure, despite the level of fibrotic remodeling that would be considered harmful in other species.

To understand whether this was a general feature of deep-sea life, the researchers compared the Greenland shark to a smaller deep-sea shark species, Etmopterus spinax.

That species showed no such fibrosis. This suggests the changes are linked to extreme longevity rather than habitat alone.

Cellular wear and tear

Another hallmark of aging is the accumulation of lipofuscin. Often called age pigment, lipofuscin forms from damaged proteins and lipids that cells cannot fully break down.

It builds up inside long-lived cells like neurons and heart muscle cells and is widely used as a marker of cellular aging.

In the Greenland shark, lipofuscin was found in massive amounts inside heart muscle cells. The pigment filled much of the cell interior, far more than what is typically seen in shorter-lived animals.

The researchers confirmed its identity using several techniques, including special stains, natural autofluorescence, and resistance to photobleaching.

For comparison, the team also studied hearts from the African turquoise killifish, a species that lives only a few months and is often used in aging research.

Older killifish hearts did contain lipofuscin, but at much lower levels and often outside the muscle cells themselves. The contrast highlights just how extreme the Greenland shark pattern is.

Survival despite cellular breakdown

At an even finer level, electron microscopy revealed what lies behind this pigment buildup. Greenland shark heart cells contained large numbers of damaged mitochondria, along with oversized lysosomes packed with dense material.

Many of these structures appeared to be autophagosomes, compartments where cells try to recycle worn-out components.

In most animals, such extensive mitochondrial damage would compromise energy production and trigger cell death. Yet Greenland shark heart cells persist.

The findings suggest that these cells tolerate a high burden of damaged components without losing function. Instead of aggressively clearing every defect, the cells appear able to coexist with them.

This tolerance may be a key feature of resilience. Rather than preventing damage entirely, the Greenland shark heart seems built to endure it over extremely long timescales.

Stress without heart collapse

The study also looked at 3-nitrotyrosine, a marker of oxidative and nitrosative stress. This molecule forms when reactive oxygen and nitrogen species modify proteins, a process linked to aging and tissue damage.

High levels of 3-nitrotyrosine are often associated with declining heart function. Greenland shark hearts showed abundant 3-nitrotyrosine staining, especially in the spaces between cells.

This pattern was similar to what is seen in aged killifish hearts, but again, without obvious signs of disease. In contrast, the shorter-lived deep-sea shark showed almost no signal.

These results challenge the idea that long life necessarily depends on low oxidative stress. Instead, they support a growing view that some long lived species survive by coping with oxidative damage rather than avoiding it.

Lessons from the Greenland shark

Together, these findings paint a striking picture. The Greenland shark heart displays many classic features of aging: fibrosis, lipofuscin accumulation, mitochondrial damage, and oxidative stress.

Yet these changes do not translate into clear functional decline, even after a century or more of life.

This disconnect points to resilience as a central principle of extreme longevity. The Greenland shark does not escape aging at the molecular level. Instead, its tissues remain stable and functional despite it.

Understanding how this resilience is achieved could reshape how scientists think about aging, not as something to eliminate, but as something that living systems can learn to live with.

By studying animals like the Greenland shark, researchers gain a rare window into biological strategies that allow vital organs to keep working far beyond the limits seen in humans.

These insights may one day help inform new approaches to protecting the aging human heart.

The study is published in the journal BioRxiv.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–