It all started when Hamnet was published in 2020. Maggie O’Farrell’s award-winning novel – the fictional story of Shakespeare’s son, believed to have died of the plague in Stratford-upon-Avon and to have inspired the play Hamlet – sent visitors to Stratford in their droves, determined to uncover the “real” story of Hamnet and his parents, William Shakespeare and Anne Hathaway.

With the film of the book newly in cinemas and Oscar nominations for its Irish leads Paul Mescal and Jessie Buckley widely anticipated, Stratford-upon-Avon is readying itself for another onslaught of attention.

Portrayed as a kind of forest sprite in the film, curled up in tree hollows with leaves in her hair, we first meet Hathaway wandering the woods with a hawk on her arm. A herbalist with psychic gifts, this is also Shakespeare’s first sight of her as he sits trapped indoors, tutoring her brothers in Latin. So begins the love affair, brought to life with passion and credibility by Mescal and Buckley.

But Hamnet is not just the story of a man’s love for a woman; it is also the deeply moving story of a mother’s love for her child. I saw the film at a press screening during which several film critics – a hardened bunch – were openly sobbing beside me. Not just a tear, mind: sobbing.

O’Farrell’s Hathaway, given blazing life by Buckley, is free-spirited and independent. It is she who urges William to go to London to seek his fortune on the stage, wise enough to know that small-town Stratford would never satisfy such an imagination.

But O’Farrell makes no bones about having invented the story of Hamnet, which as co-screenwriter with Chloé Zhao, she has translated to the screen with panache.

So when visitors clamour to be shown the herb garden at Anne Hathaway’s Cottage in Shottery, the guides reply: “How do you know she had a herb garden?”

It’s a pleasant walk through suburban Stratford to the cottage – down alleyways of high fences, past redbrick bungalows and a park. On reaching Shottery, it all turns distinctly more Elizabethan, with its village green, thatched cottages and a river babbling past Anne Hathaway’s home – picture-perfect, with mullioned windows, orchard and gardens. Yet the cottage looks nothing like it would have done in Anne’s time, say the guides, when the main building had just three rooms: a parlour, a kitchen and an open hall.

Anne’s brother Bartholomew made enough money to buy the house the Hathaways had originally rented and added a two-storey extension, expanding it to 10 rooms. Two centuries later, in the 1840s, a canny landlady and Hathaway descendant, Mary Baker, lived here. Noticing the growing numbers of visitors as Shakespeare’s fame increased, she admitted tourists and reputedly sold off slices of “original” furniture, including “Shakespeare’s courting settle”, which you can still see there. Dated to the 1700s, it’s clear Shakespeare never did any courting – or even sitting – on it, having died in 1616.

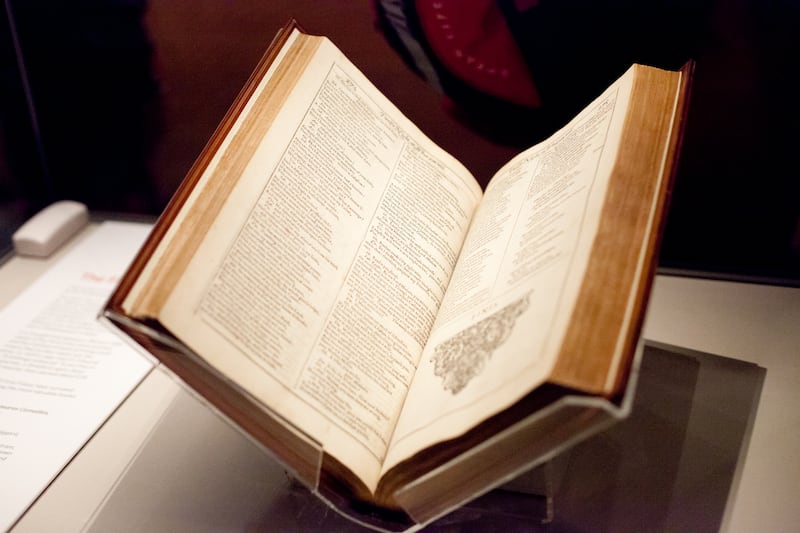

Shakespeare’s first folio

Shakespeare’s first folio  Shakespeare’s birthplace

Shakespeare’s birthplace

The Shakespeare Birthplace Trust bought the house in 1892 and while Shakespeare’s presence is felt here – there is, for example, a chair engraved with his coat of arms – it’s harder to get a sense of Hathaway. Very little is known about her, beyond that she was born around 1556 and married William Shakespeare in 1582, a ceremony thought to have taken place at the 11th-century All Saints Church in Billesley.

Parish records don’t survive to confirm the wedding, but it is known that Shakespeare’s granddaughter Elizabeth Barnard married there, leading to speculation she chose the same venue as her grandparents. It is also known that Hathaway was older than Shakespeare – 26 to his 18 – and pregnant at the time of the marriage, facts faithfully covered in the film.

The nearby manor house at Billesley is now a Marriott Bovey hotel. The medieval village of Billesley was wiped out by the Black Death – a reminder of the realities of life in Shakespeare’s England, and of the world captured in Hamnet.

After their marriage, Hathaway is believed to have lived with her husband’s family in a specially constructed extension to the Shakespeare home on Henley Street, now Shakespeare’s Birthplace, a charming 16th-century timber-framed building.

The couple’s first child, Susanna, was born in 1583; the twins, Judith and Hamnet, nearly two years later. In 1596, when he was 11, Hamnet died. A few years later, Shakespeare wrote Hamlet. It is not inconceivable that the play was inspired by the death of his son. Both the book and the film point out that the names Hamnet and Hamlet were interchangeable at the time.

O’Farrell brings her formidable imagination to this trajectory, creating a heartbreaking ending in which Hamnet and Hamlet (played by brothers Jacobi and Noah Jupe) merge reality and art on the stage of The Globe. The scene is witnessed by Hathaway, and Buckley has described it as the culmination of “this ginormous, epic journey of the heart”.

Exterior of Shakespeare’s Schoolroom & Guildhall. Photograph: Sara Beaumont Photography

Exterior of Shakespeare’s Schoolroom & Guildhall. Photograph: Sara Beaumont Photography  Jessie Buckley and Paul Mescal in Hamnet. Photograph: Focus Features

Jessie Buckley and Paul Mescal in Hamnet. Photograph: Focus Features  New Place Garden

New Place Garden

But what of Hathaway herself – the woman behind these powerful emotions? What of her life, remaining in Stratford, grieving her son, as William returns to London?

“Stratford would have been a very different place in Anne’s time,” says Dr Paul Edmondson, Local Studies Specialist for the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust. “The population was around 2,000 people, compared with over 30,000 today. It was very busy – a crossroads for Birmingham, Wales, Leicester and London.”

In 1597, Shakespeare purchased New Place on Chapel Street, where Anne lived until her death in August 1623. Though the house vanished by the mid-1700s, the grounds remain. “New Place was a big home, with between 20 and 30 rooms,” says Edmondson. “Anne was responsible for running it. I imagine her as strong and confident.”

Standing in the gardens of New Place, I try to see her, this strong, confident woman. There are many negative stories about her. She isn’t even graced with her married name, Shakespeare, instead being eternally recorded as Anne Hathaway. “There’s a lot of misogyny around Anne in Shakespeare’s biographies,” Edmondson says, pointing to Germaine Greer’s “excellent” book Shakespeare’s Wife as bucking the trend.

A short walk from New Place brings me to the banks of the Avon, where the Royal Shakespeare Company has made its home since 1961. The transformed Royaroyl Shakespeare Theatre reopened in 2010, offering plays, backstage tours and riverside dining. Across the road, The Arden Hotel is a good place to stay, its rooms overlooking the river and summer outdoor performances (B&B from £129, theardenhotelstratford.com).

Arden hotel

Arden hotel  The river Avon

The river Avon

It’s said Shakespeare wrote in these gardens – but there is scarcely a garden or house in Stratford that doesn’t claim that honour.

To visit a room he definitely wrote in, you can take an interactive lesson with a slightly testy schoolmaster at the Shakespeare Schoolroom on Church Street, where the young William probably first heard the legends that inspired some of his plays.

As anticipation builds for the Oscar nominations on January 22nd, meanwhile, Stratford is also bracing itself for another influx of visitors. “While it’s unclear how the release of Hamnet will impact visitor numbers, the potential is very exciting,” says Darren Tosh of Shakespeare’s England.

For more information, visit shakespeares-england.co.uk. Bernadette Fallon was a guest of The Arden Hotel