An artistic impression of Nova V1674 Herculis. Credit: CHARA Array

An artistic impression of Nova V1674 Herculis. Credit: CHARA Array

Astronomers pictured novae—the violent explosions that occur on the surface of white dwarf stars—as simple, spherical fireballs. You could think of them as the universe’s flashbulbs: one big pop, a blinding light, and then a slow fade. But when researchers recently pointed the high-powered CHARA Array telescope at two erupting stars, they saw something very different.

New high-resolution images of these stellar cataclysms have revealed that novae are actually messy, complex events involving perpendicular jets of gas and delayed eruptions that engulf entire star systems.

“The fact that we can now watch stars explode and immediately see the structure of the material being blasted into space is remarkable,” says John Monnier, a professor of astronomy at the University of Michigan.

This leap in imaging technology is transforming our understanding of stellar evolution. As Monnier puts it, “It opens a new window into some of the most dramatic events in the universe.”

From Grainy Photos to High-Def Video

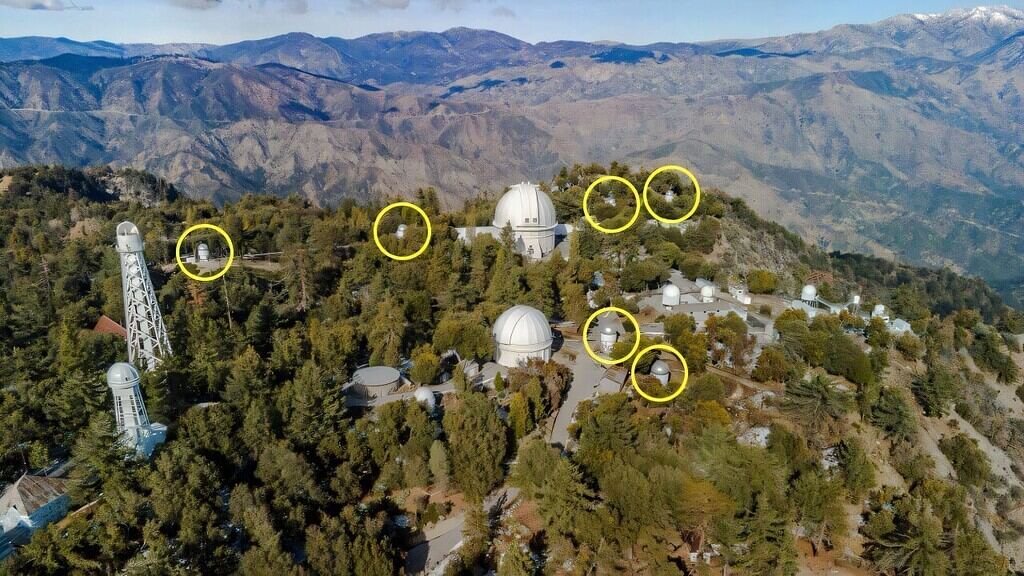

The circles mark the domes of the six CHARA Array telescopes at the historic Mount Wilson Observatory. Credit: Georgia State University/The CHARA Array

The circles mark the domes of the six CHARA Array telescopes at the historic Mount Wilson Observatory. Credit: Georgia State University/The CHARA Array

The breakthrough comes from the Center for High Angular Resolution Astronomy (CHARA) Array in California.

By linking six telescopes together using a technique called interferometry, the observatory can achieve the resolution necessary to see the tiny, rapidly expanding debris fields of stars thousands of light-years away. The CHARA Array is basically a giant, distributed eye composed of six individual telescopes scattered across the peaks of Mount Wilson, all linked together to behave like one massive 330-meter instrument.

When we see a nova, we aren’t just looking at one star; we are looking at a high-stakes celestial robbery. These events occur in interacting binaries, where a tiny, incredibly dense white dwarf (about the size of Earth but with the mass of the Sun) siphons hydrogen-rich gas from a larger companion star. Once that gas builds up, it triggers a thermonuclear runaway—a nuclear explosion on the white dwarf’s surface that we see as a “new” star in the sky.

“Instead of seeing just a simple flash of light, we’re now uncovering the true complexity of how these explosions unfold,” says Elias Aydi, a lead author of the study and astrophysicist at Texas Tech University. “It’s like going from a grainy black-and-white photo to high-definition video.”

×

Thank you! One more thing…

Please check your inbox and confirm your subscription.

This clarity allowed the team to track two very different explosions in 2021: V1674 Herculis, a “speed demon” that flashed and faded in days, and V1405 Cassiopeiae, a “slow burn” that lingered for months.

The Speed Demon and the Shock Waves

The images reveal the formation of two distinct, perpendicular outflows of gas, as highlighted by the green arrows. The panel on the right shows an artistic impression of the explosion. Credit: CHARA Array

The images reveal the formation of two distinct, perpendicular outflows of gas, as highlighted by the green arrows. The panel on the right shows an artistic impression of the explosion. Credit: CHARA Array

This new clarity allowed the team to track two very different explosions in 2021. The first was V1674 Herculis, a “speed demon” that flashed and faded in days.

V1674 Herculis was a record-breaker. It erupted in the constellation Hercules on June 12, 2021, and skyrocketed to peak brightness in less than 16 hours. When the CHARA team captured images just two days after the explosion, they found something unexpected.

When the CHARA team captured images just two days after the explosion, they found something unexpected. The explosion wasn’t an even, round shell. Instead, the star was spitting out material in two distinct, perpendicular flows.

“The images give us a close-up view of how material is ejected away from the star during the explosion,” says Gail Schaefer, director of the CHARA Array.

These conflicting flows of gas created a violent environment. The ejecta streams slammed into each other, creating shock waves powerful enough to emit gamma rays. NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope picked up high-energy signals from the star at the exact same time the CHARA images showed the outflows emerging.

This confirmed a major hypothesis: the gamma rays we detect from these explosions are produced by internal collisions within the debris field, not just the blast wave hitting interstellar space.

The Slow Burn and the Common Envelope

If V1674 Herculis was a sprint, V1405 Cassiopeiae was a marathon. Discovered in March 2021, this nova took a staggering 53 days to reach its maximum brightness.

For nearly two months, the star baffled astronomers. The initial CHARA images showed a bright, compact central source with a radius of about 0.85 astronomical units (AU)—roughly the distance from the Sun to Venus.

This was weird. If the star had blown its outer layers into space on day one, the debris shell should have been massive by day 53—somewhere between 23 and 46 AU wide. But the shell was missing.

The best explanation is a phenomenon known as a “common envelope” phase. Instead of ejecting the material immediately, the white dwarf likely swelled up, swallowing its companion star inside a cloud of hot gas. The two stars orbited inside this shared atmosphere, churning it up like a mixer, until the material was finally flung out weeks later.

Laboratories for Extreme Physics

These findings turn these dying stars into local physics labs.

“Novae are more than fireworks in our galaxy—they are laboratories for extreme physics,” says Laura Chomiuk, a study co-author from Michigan State University.

“By seeing how and when the material is ejected, we can finally connect the dots between the nuclear reactions on the star’s surface, the geometry of the ejected material and the high-energy radiation we detect from space.”

Understanding these shock waves helps us grasp phenomena far beyond our own galaxy, from super-luminous supernovae to the mergers of stars that ripple the fabric of spacetime.

We used to think of novae as simple switches flipping on and off. Now we know they are complex engines of creation and destruction, driven by binary mechanics and fluid dynamics that we are only just beginning to map.

“Catching these transient events requires flexibility to adapt our night-time schedule as new targets of opportunity are discovered,” Schaefer notes. As telescopes get sharper and our response times get faster, the night sky is looking less like a static backdrop and more like a volatile, evolving frontier.

The findings appeared in the journal Nature Astronomy.