Economic data from federal agencies has come under question recently as the Bureau of Labor Statistics struggles to generate sufficient response to its survey requests, resulting in large revisions after the initial reporting.

This decline in the timeliness of the data harms the ability of businesses and investors to make decisions.

As a result, many businesses are turning to private label data to understand employment, inflation and the greater condition of the real economy.

Get Joe Brusuelas’s Market Minute economic commentary every morning. Subscribe now.

For years systemically important financial institutions, financial intermediaries and private firms have used private label data to manage their businesses.

Private estimates of employment, inflation and growth are not new and have expanded the universe of information.

Homebase, Indeed and Bloomberg, for example, provide alternative employment data that economists use to forecast payroll growth and unemployment. Unlike the government data, though, the private label data comes at a cost.

We think that this use of private label data is about to accelerate as criticism of data from the federal government increases with each revision.

This shift is more than an arcane discussion about economics. The Federal Reserve depends on this stream of government data to set its policy and achieve its mandates for price stability and full employment.

Should the combination of low response rates to the BLS surveys and criticism of the quality of publicly derived data continue, at some point the Fed, the private sector and the public will need to look for bespoke estimates of economic activity.

At the center of this discussion in the monthly jobs data, and how to improve it. We have three suggestions:

Look at the change, not the total. In an ever-changing economy where 163.3 million people are employed, the several thousand new or lost positions seem inconsequential. Instead of focusing on the total, measuring the percentage change in the workforce compared with a year earlier might be more relevant in determining the strength of the labor market. Other measures of economic activity are viewed through this lens.

Emphasize the service sector. The service sector comprises 84% of total employment in the American economy, with manufacturing and government employment likely to continue losing ground as technology takes hold. Looking at the percentage change in private service-sector employment would provide a better reading of the health of the economy.

Look to alternative sources of data. We would urge our friends in the financial and mainstream media to step up their coverage on alternative private label sources of employment data.

For example, the BLS also calculates the consumer price index, which is likely to draw more scrutiny should inflation accelerate. There are already several alternatives to the CPI, including the Fed’s preferred measure of inflation, the personal consumption expenditures index calculated by the Bureau of Economic Analysis.

There are also several inflation indices produced by the regional central banks and a variety of private label sources like The Billion Prices Project at Harvard and MIT.

As for employment, we find the ADP payroll data a suitable alternative to the BLS survey, with the indisputable benefit of originating from private sources.

ADP as an alternative

Wall Street has long relied on the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ monthly release of nonfarm payroll data to assess the state of the economy.

But as the labor market evolves, we think attention will be turning to the estimates of private payrolls from Automatic Data Processing Inc.

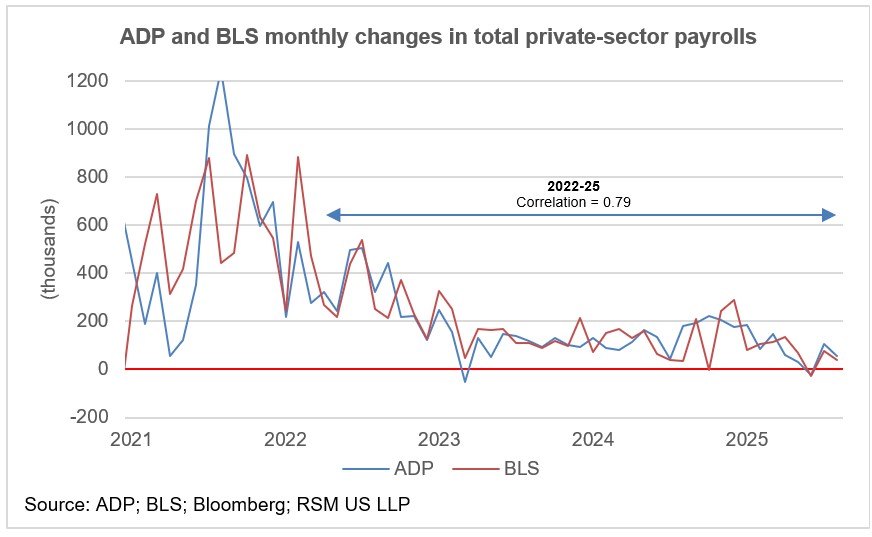

Changes in the number of paychecks processed by ADP appear to conform to the final revised version of private (non-government) nonfarm payrolls as surveyed by the BLS. But as opposed to BLS surveys, the ADP number is based on hard data: the number of paychecks actually processed each month.

As for timing, the BLS survey comes out the first Friday of the following month and is revised twice during that month. There have been revisions in all but three of the months since 1979, with most usually overlooked unless there has been a dramatic increase or decrease.

Our research has shown that revisions tend to follow the direction of the economy, with positive revisions present during business cycle upturns and negative revisions present when economic growth is slowing.

The size of the BLS revisions in recent months suggests that some financial asset prices are slow-walking the potential of an economic downturn.

The ADP monthly data is available at the end of each month or in the first days of the following month. It’s also subject to frequent revisions as new data becomes available, and this needs to be better advertised.

Preliminary results

The ADP number of paychecks processed and the final revised BLS change in private-sector payrolls have a correlation coefficient of 0.79, where a coefficient of 1.0 implies a one-to-one movement of the two measures.

In our opinion, the ADP data has never garnered the same attention from Wall Street economists and traders as the government reports have, perhaps because the BLS data offers a single, easy-to-understand number and because the ADP data does not consistently predict the initial estimate of monthly jobs data from the BLS.

While we do not expect that to happen overnight, we think attention should shift to the abilities of the ADP and BLS data to predict changes in the business cycle.

For that, it might be more useful to incorporate the levels of employment and percentage changes rather than the singular focus on what is represented as the number of jobs created.

Looking at payroll levels

The 10-year correlation between the ADP total payrolls and the BLS private-sector hiring during the 2010-19 recovery was nearly perfect,

But while the ADP payrolls flattened out in 2019, the BLS number continued higher. The ADP number might have been a better measure of what was to come.

And the BLS surveys of employee losses in 2020 were more severe than estimated by ADP, perhaps because of the presence of off-the-books employment in the BLS survey or other anomalies in a crisis situation.

This year, payrolls in both the ADP and BLS reports are flattening out, with significant decreases (private hiring and government employment), in March, April and May.

That leveling off should not be a surprise. Large-scale layoffs in the federal government were taking place while uncertainty around tariffs led to cautionary hiring practices in the private sector.

From 2010 through 2019, BLS payrolls grew at an average rate of 1.9% per year.

From 2023 through 2024, yearly BLS payrolls grew at an average yearly rate of 1.2%. In the first seven months of this year, payroll growth has slowed to a yearly rate of 0.72%.

Percentage changes in payroll levels

If the purpose of analyzing the labor market to predict the direction of GDP growth, we suggest measuring the health of both indicators in the same manner.

The yearly percentage change in ADP payrolls has a correlation coefficient of 0.72 with real GDP growth. The BLS service-sector survey has a slightly higher correlation with real GDP of 0.78.

But the ADP data appears to be a better predictor of GDP from 2011 until 2019, before leading the drop in GDP during the 2019 trade war and the runup to the pandemic shutdown.

The yearly change in the BLS service sector data is flat throughout 2011-20 but seems to be a better predictor during the pandemic and recovery.

The takeaway

From our point of view, federal government statistics remain the gold standard upon which to make important policy and private sector allocative decisions. But the methodologies in the collection of that data are not perfect and are facing increased competition from private sector label data.

In a perfect world, more resources—capital and personnel—would be given to the collection of data and provided free to the public.

We do not live in that perfect world and the reality is that the reliance upon private label data is set to become far more important.

By using a widely available data set from ADP, our research implies that the relative growth of actual payrolls might offer a better perspective on the economy than a single number that can be distorted by survey responses.

The number of paychecks processed by ADP appears to be highly correlated with BLS survey estimates, while potentially avoiding criticism thrown at federal agencies.

We are confident that as the $30 trillion American economy evolves, that the rise of private sector data will become far more important and publicly recognized that has traditionally been the case.