Bernard Arnault, one of the world’s wealthiest men, with a net worth of $156 billion (£116 billion), has weighed into a bitter debate raging in his native France over the proposed imposition of a 2 per cent tax on the country’s mega-rich — those with assets over €100 million (£87 million) — calling it “an offensive that is deadly for our economy”.

Political support has been growing in recent weeks for a call by Gabriel Zucman, a prominent left-leaning economist, for the levy, which he claims would raise €20 billion from taxing about 1,800 of France’s richest households — enough to cover almost half of the hole in the government’s finances that Sébastien Lecornu, the recently appointed prime minister, needs to fill.

Arnault, who is the chief executive and chairman of LVMH, the parent company of luxury fashion brands Louis Vuitton, Dior and Tiffany & Co, said: “This is clearly not a technical or economic debate, but rather a clearly stated desire to destroy the French economy.”

In a statement to The Sunday Times, Arnault, 76, dismissed Zucman as “first and foremost a far-left activist … who puts at the service of his ideology (which aims to destroy the liberal economy, the only one that works for the good of all) a pseudo-academic competence that is itself widely debated”.

Gabriel Zucman

NATHAN LAINE FOR THE SUNDAY TIMES

The mooted introduction of a wealth tax is rocking the French economy. A poll by the French Institute of Public Opinion (Ifop), shows 86 per cent of people back the proposal. President Macron’s appointment this month of Lecornu as prime minister has made a wealth tax more likely. The opposition Socialist party, whose votes Lecornu needs to pass his budget, has demanded adoption of the tax as a precondition for their support.

In France, Zucman has become a household name. Last Thursday, half a million people took part in a general strike dominated by calls for greater social justice.

“Zucman Tax. Ultra rich, pay up,” read one banner being carried towards the Place de la Bastille.

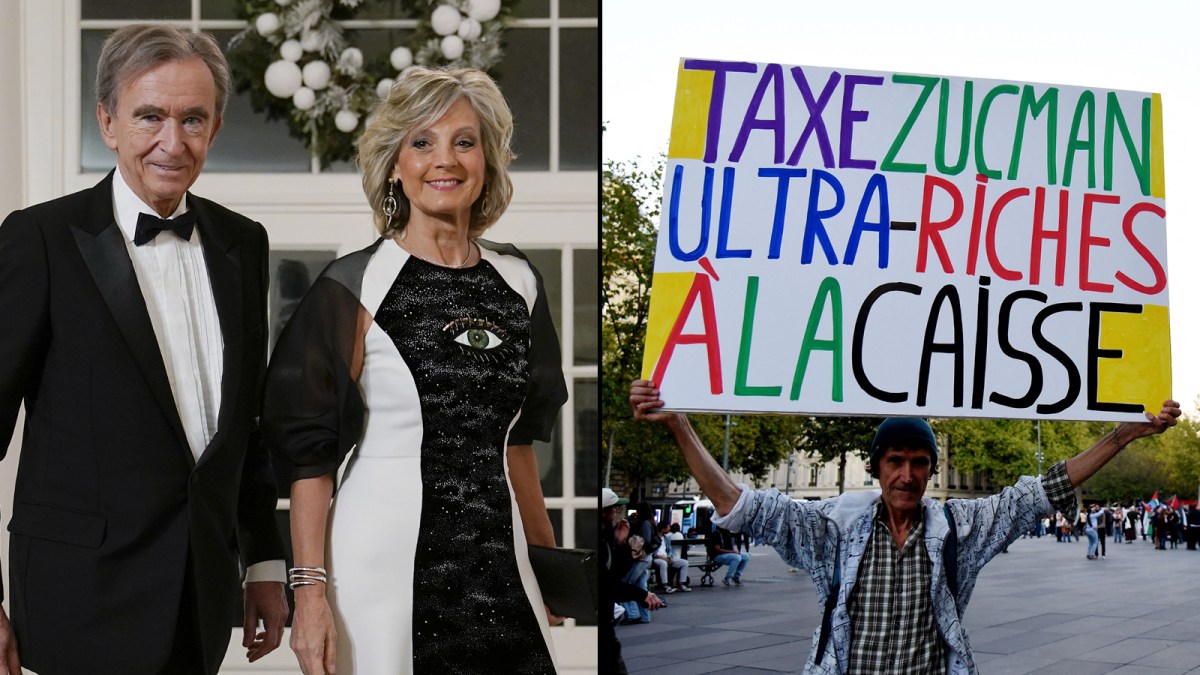

A supporter of the Zucman tax at the Let’s Block Everything protest in Toulouse this month

FRED SCHEIBER/SIPA/SHUTTERSTOCK

Zucman, 38, is a former student of Thomas Piketty, “the rock-star economist” who first made waves in the 2010s with his work on economic equality. He explained his philosophy in an interview last week in his office in the prestigious École normale supérieure, a modern building in southern Paris.

Dressed informally in a white T-shirt, the father of three had pedalled through the gathering crowds across the city. He did not seem especially pleased to have his name on the proposed tax — or the banners. “I would prefer it if it were called the Bernard Arnault tax,” he added, speaking in English he perfected while teaching at the University of California, Berkeley.

“People understand the basic reality that the super-rich don’t pay enough tax,” he continued, arguing that the current tax system creates “a kind of snowballing effect for billionaires”.

While most people can save only out of what is left after they have paid their taxes, the mega-rich can effectively do so out of their gross income. “So their wealth just keeps growing very, very fast, much faster than the rest of the population’s.”

• Young, angry, educated — and raring to rebel

Zucman has become inured to criticism. In recent days Patrick Martin, the leader of Medef, the employers’ federation, accused him of plotting to expropriate the business community, while Philippe Corrot, co-founder and chief executive of Mirakl, a multibillion-pound e-commerce platform, claimed he was creating a “deadly trap that will destroy the French tech sector and its 1.3 million jobs”.

Responding to Arnault’s comments, Zucman denied he had been an activist in any movement or party and said he had won numerous awards for his work as an economist, including America’s prestigious Clark medal. “Coming from one of the richest men in the world and in a context where academic freedoms are being challenged in a growing number of countries, this rhetoric is disturbing,” he said. “This measure would simply ensure that billionaires contribute to public expenses at the same rate as other citizens.”

There has nevertheless been considerable doubt over the effectiveness of taxing the mega-rich, especially when the taxes are introduced unilaterally. Only a handful of countries in the world, such as Norway, Spain and Switzerland levy a wealth tax, while the revenue raised pales in comparison with the receipts from income tax or VAT.

A protester at Thursday’s demonstration in the Place de la République, Paris

APAYDIN ALAIN/ABACA/SHUTTERSTOCK EDITORIAL

France’s own experience has been disappointing: its most recent attempt at a wealth tax a decade ago, under François Hollande, raised only a few hundred million euros, a tiny fraction of government revenue, and prompted some of the country’s wealthy to leave, with some moving to London.

Zucman describes Hollande’s efforts to soak the rich, which included a 75 per cent supertax imposed in 2012 on earnings above €1 million, as a “total joke … invented 30 minutes before going on television”.

One of Macron’s first actions after becoming president in 2017 was to abolish the tax and replace it with a levy on property alone, which excluded financial assets, in which the mega-rich tend to hold most of their wealth.

Zucman’s critics say his own tax is unlikely to work any better. In a joint opinion piece published in Le Monde this month, seven leading economists claimed it would raise just €5 billion a year, a quarter of what he predicts.

This, they said, would be in large part because the super-rich would modify their behaviour — or simply leave France.

“Conservative people look at this historical experience and say the wealth tax didn’t work and will never work,” he said. “I think we can be a bit more constructive: we can learn about the mistakes that were made and how to fix them.”

Crucially Hollande, like François Mitterrand, a fellow socialist who was president from 1981, exempted wealth owned by entrepreneurs in the form of shares in their companies, a massive loophole that Zucman’s own proposed tax aims to clos

Zucman believes a tax on the mega-rich is the way out of France’s budget woes. In 2010, the combined wealth of France’s 500 richest households was €200 billion, but by last year it had jumped sixfold to €1.2 trillion, taking it from 12 per cent of GDP to 42 per cent, according to Challenges magazine, which compiles the French equivalent of The Sunday Times Rich List.

Measuring people’s assets would not be difficult, especially in a country with a history of wealth taxes, he believes. Shares in publicly listed companies would be valued at market prices; those of fast-growing start-ups not yet listed could be assessed on the basis of values put on them during funding rounds.

Zucman also dismisses suggestions that the mega-rich will all simply leave France. Despite widespread reports of an exodus from Britain in response to its recent dismantling of the advantageous “non-dom” tax regime, he says that academic studies, including one done recently in Scandinavia, show the mega-rich are not as mobile as widely assumed.

“Okay, a few people will leave, but the aggregate effects on the economy will be modest,” he said.

To deter them, Zucman suggests a form of exit tax, known as an “anti-exile” shield, that would require those who leave to continue paying their dues for another, say, five or ten years, which he says is possible given a greater willingness in recent years for countries to exchange bank information.

“If people violate the law, the government is going to seize their assets, it’s going to arrest them at the airport when they come back. That’s the risk they will have to take,” he said.

Wealth taxes are at the forefront of public debate, not just in France, but also in America and Britain, where Rachel Reeves, the chancellor, looks poised to come up with ever more imaginative ways of tapping into people’s assets in this November’s budget.

Zucman has become a leading figure in the debate. Last year he produced a report for the G20 summit in Brazil that called for a 2 per cent levy on the world’s estimated 2,500 billionaires, although securing agreement would be difficult and could take years.

Nor is Zucman concerned it will put off a new generation of entrepreneurs from pursuing their dream. “I’ve never met someone aged 25 or 30 saying they’re scared about paying a 2 per cent tax once they have more than a hundred million or a billion dollars,” he said.

• No tax, no crime, no free speech. So would you move to Dubai?

The fate of Zucman’s proposal remains uncertain. Although supported by the left, it has so far been opposed by Lecornu’s main power base, Macron’s centrist Renaissance party and the Republicans, to their centre-right, although some of their MPs are beginning to speak out in favour of the tax. Polls show their voters overwhelmingly back it too.

If the tax is implemented and works, Zucman does not rule out the €100 million threshold being reduced to hit the merely affluent as well as the mega-rich — even perhaps people such as his parents, both doctors, whose own property and other investments make them, in his words “small multimillionaires”.

“I’m a bit of a class traitor,” he laughs.

Bernard Arnault’s remarks in full

STEFANO RELLANDINI/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

“It is impossible to understand Mr Zucman’s positions if one forgets that he is first and foremost a far-left activist. As such, he uses his pseudo-academic expertise — which itself is the subject of widespread debate — to serve his ideology (which aims to destroy the liberal economy, the only one that works for the good of all). This is why he presents the French tax situation in a biased way.

“After all, how could he directly involve me when I am certainly the largest individual taxpayer and one of the largest professional taxpayers through the companies I run? Any other comment seems pointless, as this is clearly not a technical or economic debate, but rather a clearly stated desire to destroy the French economy.

“I cannot believe that the French political forces that govern or have governed the country in the past could lend any credibility to this offensive, which is deadly for our economy.”