Read all of Slate’s stories about the 25 Greatest Picture Books of the Past 25 Years.

Mo Willems has thought a lot about what kind of work picture books should do. He’s fond of saying that his job is to create 49 percent of the story and let children fill in the other 51 percent from their own imaginations. Willems’ run of prize-winning bestsellers suggests he’s on to something: From his 2003 debut, Don’t Let the Pigeon Drive the Bus!—a shoo-in for Slate’s 25 Best Picture Books of the Past 25 Years—Willems has made books that break the rules of children’s lit, that delight young and old readers equally, and that make kids think about what a book even is. Willems came to picture books from TV animation and, two decades later, still sounds grateful he made the switch. All the books in Slate’s 25 Best Picture Books list, he points out, feature individual voices. “These are people writing letters to themselves that they want someone else to pay for,” he said. “And the greatness of this industry is the variety of letters that can be written.”

For this package, we’ve been asking authors and illustrators to discuss the decisions influencing a single page or spread from their book. When I asked Willems if there was a particular page he wanted to discuss from Don’t Let the Pigeon Drive the Bus!, however, he replied that what he found most exciting about picture books was not a single page but the page turn. Together, we explored the Pigeon’s central freak-out, starting with the page before that freak-out occurs. Our conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Hyperion Books for Children

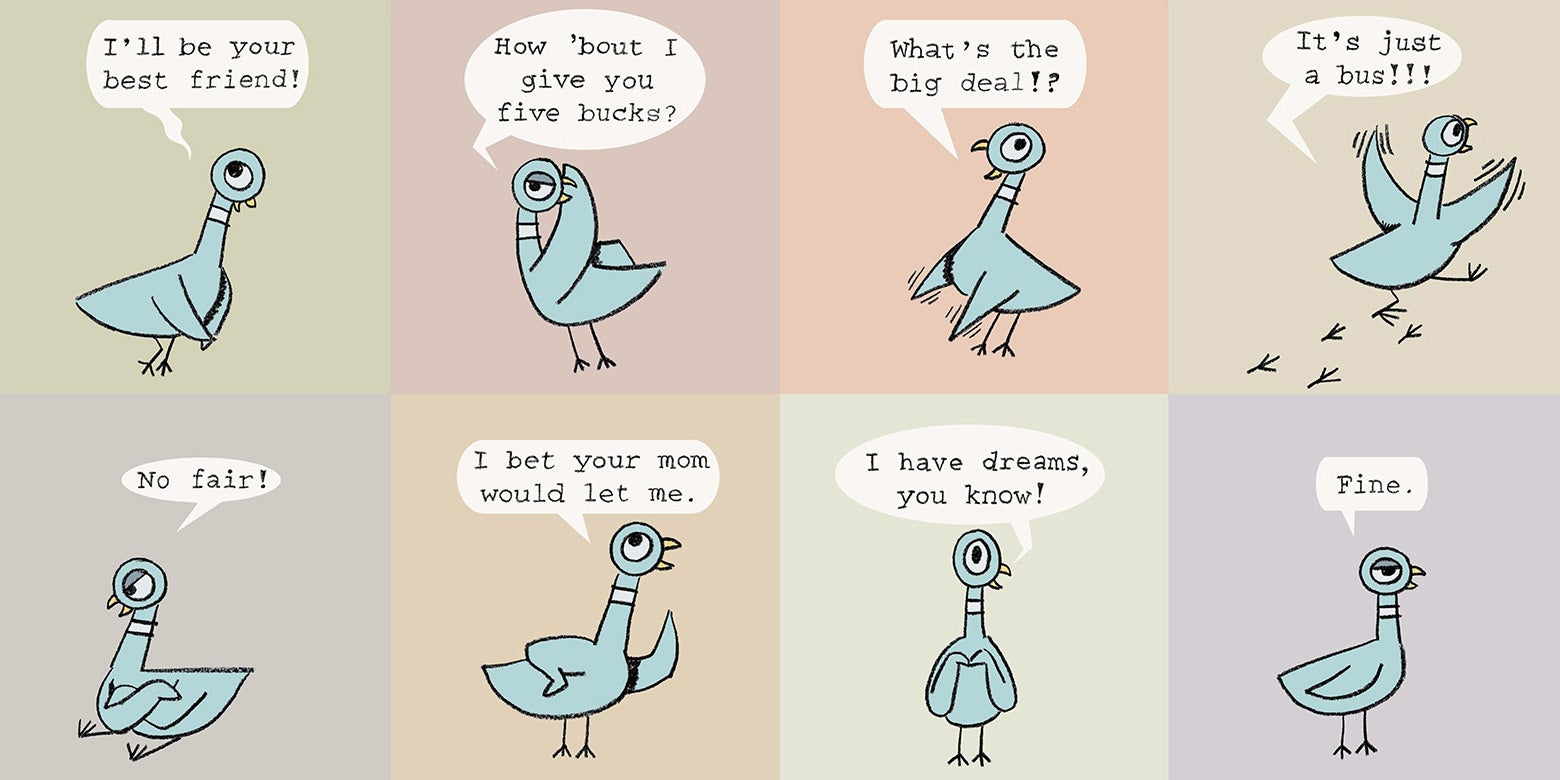

Mo Willems: OK, so when someone reads a book, they try to spend the same amount of time on each page no matter what.

Dan Kois: Meaning when an adult reads aloud?

When an adult reads to a kid, each page, you’re going to spend the same amount on the page. So when you have eight images on a spread like this, you’re going to read that four times as fast as single images.

That definitely was my experience every time I would read this book to my kids. Like, I’d read them rat-a-tat-tat.

You can’t help because you want to spend the same amount of time as you did on the single-page lines, so you find yourself inadvertently getting faster. I was writing a score, but while I was ceding control to the orchestra, I could still establish a sense of rhythm.

The orchestra is me, reading to my kids.

Like classical music, it’s going to be performed differently every time it’s performed. I’m trying to manipulate your rhythm to match what I’m hoping the kid’s sense of humor would be.

How did the design of the Pigeon come around? Here, we have the Pigeon in eight frames—why does it look this way?

I wanted it to be as simple as possible. When I design a character, it’s reductive. I take away lines until just before it’s abstract. And then I know that any 5-year-old can draw it. And, more importantly, that a parent can recognize what they’re trying to draw and then make a comment about that.

So you’re working off the assumption that a child is going to try and reproduce this in some way?

Because a book is meant to be played, not just to be read. And this is a format. Don’t let the Pigeon drive, don’t let the Pigeon whatever. It’s easy to come up with the next one. Don’t let the Pigeon eat pizza! So it’s already inviting that kind of infringement. So the character has to be simple enough to draw that you’re not getting stuck on rendering the character. You can really let your ideas flow.

And yet this spread demonstrates how expressive that simple character can be. The Pigeon is giving off eight very discrete attitudes in these panels.

Right. I agree. The one formal element of this is that the eye, the window to the soul, is always the biggest and the darkest because you look at the darkest part of a drawing first. So the idea would be that you would see the eye first and then let the silhouette of the body tell the rest.

But you never even give yourself two eyes. You only have one eye on the Pigeon.

What a waste of eyes. I am a busy man, Dan.

Yeah.

No, I think it needs to be really that simple. The other thing is, with only one eye, you know that Pigeon is looking at you. And it’s very important to me not only that kids be seen, but that kids realize that they are seeable, because there are kids who live in environments where they don’t feel seen or seeable. And so the Pigeon is always interested in you. You have power and you are interesting. I think in two eyes, you wouldn’t get that as much.

How did you decide to do speech bubbles as opposed to a traditional picture-book format, the text underneath or whatever?

It felt more immediate. If it was like, “The Pigeon said, ‘I’ll be your best friend’ ” …

Right.

You’re cutting out the middleman. The original premise of this book, when I was first playing with it, was it was a kid whose job was not to let the Pigeon drive the bus. The real breakthrough was firing the kid.

The reader is the kid.

I already have a kid. The kid is you. The Pigeon is with you. So where are you? The Pigeon is where you are.

You may get rid of that intermediary in the structure of the book, but you’re always forced, as you say, to have this other intermediary, the adult who’s reading it.

Right.

The Unlikely Story of the Secretary Who Inspired One of Music’s Greatest Songs

I Can’t Believe That NBC Let Jordan Peele Make This Movie

One of the Funniest Documentaries of the Year Is Streaming for Free on YouTube

This Content is Available for Slate Plus members only

Please, Lord, Do Not Make Me Roll Hard for Jimmy Kimmel

One thing that the book does is it forces the adult to buy into the madness. There’s no way to read this book without inventing a wacky voice for the Pigeon.

That’s right. “Look at this adult who is usually serious or telling me to do whatever—they’re being silly!” Very, very exciting. And the Pigeon has to be a picture book rather than an early reader because when you are in a picture-book stage, you will be forgiven because most of your cultural life is with a grown-up. And so you can say terrible things and be forgiven.

But in early readers, most of your cultural life is at school, and you cannot say terrible things and be forgiven. You might lose your friend. That’s why Elephant and Piggie are early readers. They’re constantly repairing their friendship. The Pigeon wouldn’t survive in that milieu because another character would just be like, “I don’t need you,” and walk away.

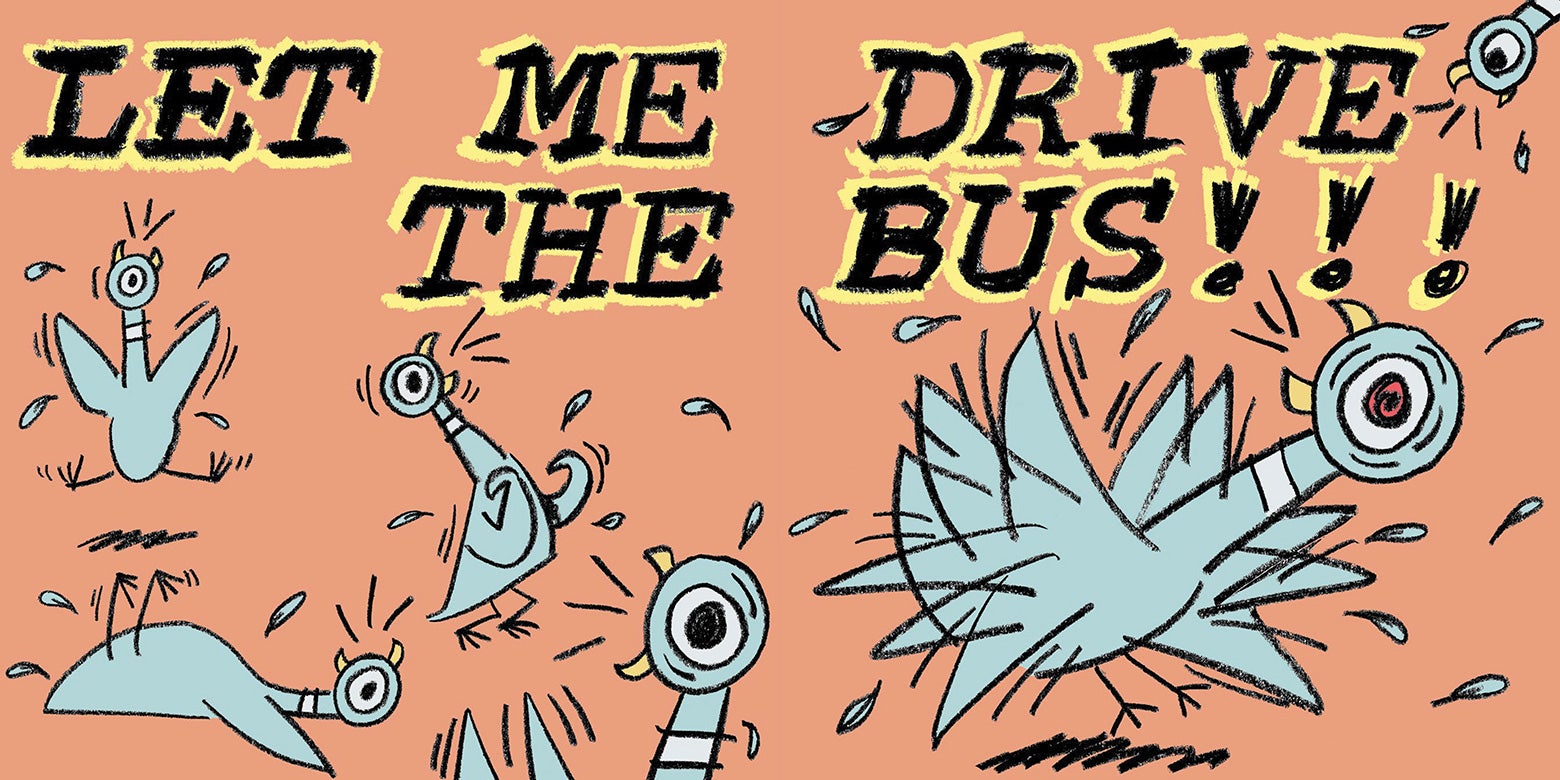

Let’s talk about the page turn as an action. You turn the page and there’s this explosion.

When you turn the page, the first Pigeon you see is the big one, right? And its bright red eye. I mean, it’s just staring at you.

Hyperion Books for Children

It’s the first time you have saturated colors. It’s the first time where there’s a full spread with just one big sentence, multiple images. And then you see all these Pigeons. And you know intuitively that four siblings did not show up. Right?

You understand it’s like the fractured inner soul of the Pigeon expressing itself.

And you get a lot more of the sort of crunchiness. The line gets worse and scratchy and dirtier to imply that it was drawn faster. Like, “I don’t have time for this. I’m so frustrated.”

Hyperion Books for Children

Yeah. And where previously the text has been a carefully hand-drawn typewriter font, here the text goes berserk.

The text is no longer concerned with kerning or the delicacies of whether it is serif or non-serif.

There’s no way to read this without cutting loose.

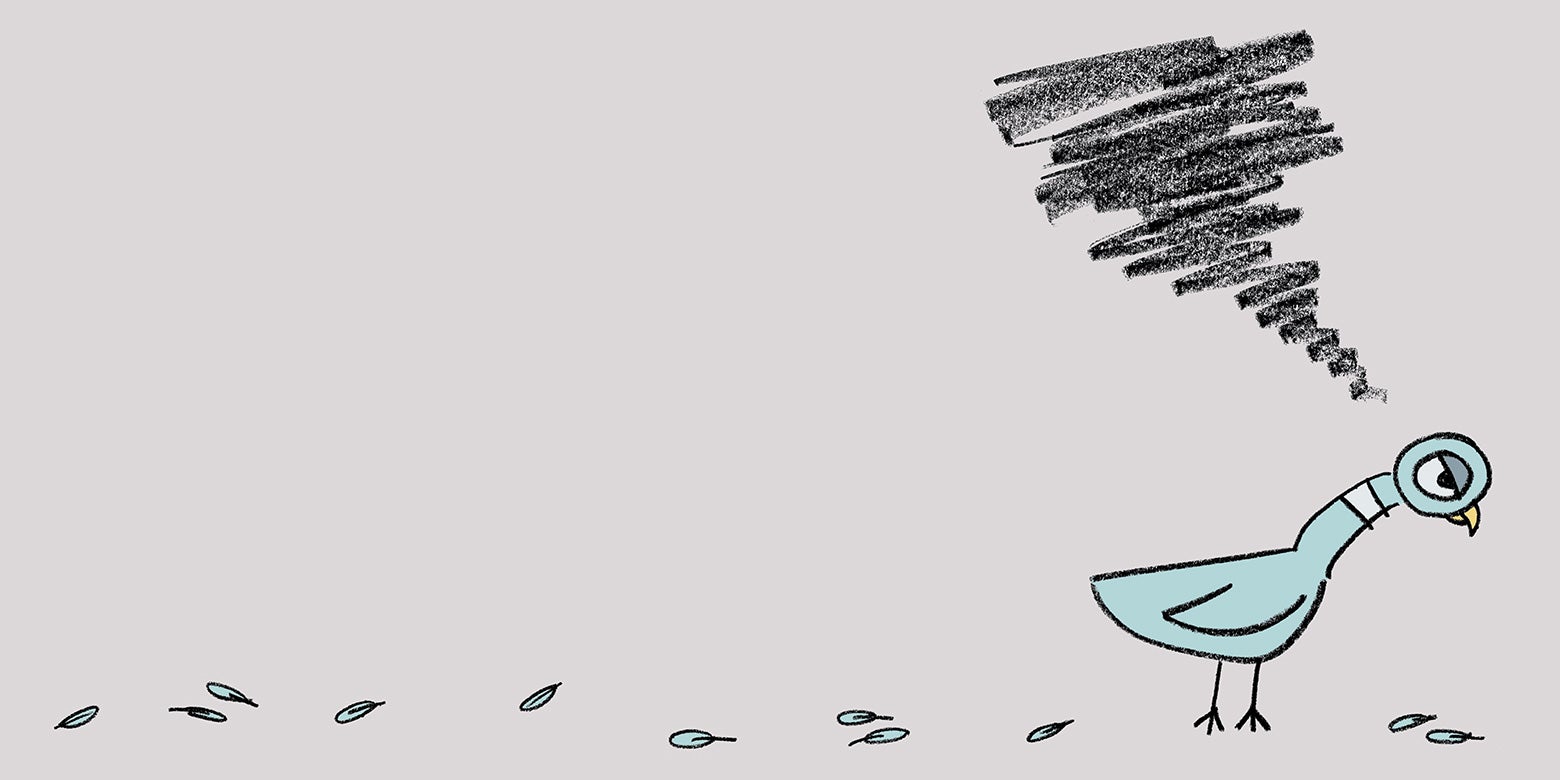

You have to yell it. You cannot speak it. And then on the next page—

Hyperion Books for Children

You have to make a sound here.

Right.

What is that tornado thing? You have to make up what that sound is.

Dan Kois

In Our Poll About the Best Picture Books of the Past 25 Years, One Got More Votes Than Any Other

Read More

I always loved making that sound. It’d always be, like, [exasperated Pigeon sound].

Yeah. [Different exasperated Pigeon sound.] The Pigeon gets misunderstood. The Pigeon is, like children, un–listened to, not taken seriously. Ultimately, when the Pigeon is getting angry, it’s not because it’s having a fit; it’s because it’s not being listened to. It’s not being heard. And I do fear sometimes that books tell kids what to do rather than what is. Right?

What do you mean?

What is is: Things you think are super important, you’re not going to get now. It’s just not going to happen. You cannot be a ballerina astronaut today. Today is not the day. So what do you do with that? It’s more interesting than prescribing behavior.

When I would read the Pigeon to my kids, my takeaway was always “Oh, the Pigeon pesters the reader just like you, my child, pester me.” And my child’s takeaway was “I can’t believe that the Pigeon doesn’t get to drive the bus.”

It’s a real litmus test.

Get the best of movies, TV, books, music, and more.