Kenya is experiencing an unusual internet problem. While the country’s hunger for bandwidth grows stronger each quarter, the actual pipes delivering that connectivity are shrinking.

The Communications Authority reported that Kenya’s available international bandwidth dropped 12.5% to 19,381 Gbps in the second quarter of 2025, down from 22,148 Gbps three months earlier.

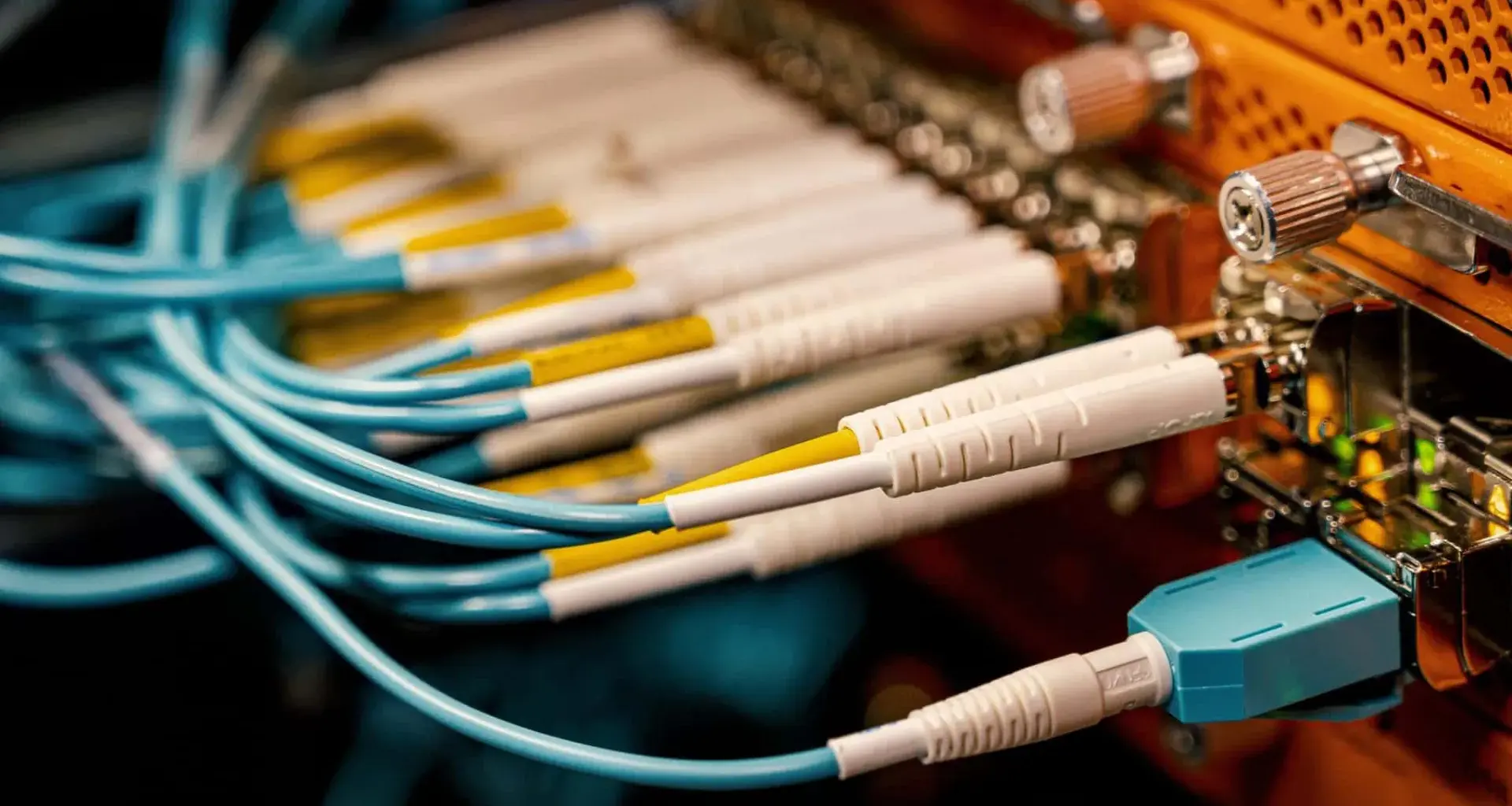

This decline stemmed from capacity adjustments on major undersea cables like SEACOM and EASSy, which carry most of Kenya’s international internet traffic.

However, demand told the opposite story. Kenyans actually used 10,735 Gbps of undersea capacity during the same period, up from 9,589 Gbps in the previous quarter.

This created an unprecedented situation where less bandwidth was available but more was being consumed.

Kenya now uses roughly 55% of its available international bandwidth, the highest utilization rate on record. When internet infrastructure operates at such high capacity levels, networks become more vulnerable to congestion and outages.

This isn’t happening in isolation, though. Mobile broadband consumption reached 620 billion GB in the fourth quarter, with 4G networks handling over 80% of all mobile subscriptions.

Fixed internet connections grew even faster, jumping 42.9% year-over-year to exceed 2.1 million subscribers. Both fiber and wireless networks expanded rapidly to meet this demand.

Businesses rely increasingly on cloud services, streaming platforms consume massive bandwidth, and remote work has become standard for many professionals. Kenya’s economy now depends on fast, reliable internet in ways unimaginable just a decade ago.

For internet service providers, higher utilization rates mean higher costs. They must purchase more capacity on wholesale markets, and when supply tightens, prices typically rise.

These costs eventually reach consumers through slower speeds during peak hours or higher monthly bills.

READ: Safaricom and Meta Invest $23 Million in New Kenya–Oman Subsea Cable

The capacity crunch also creates opportunities for other players. Satellite internet providers like Starlink may find openings in rural areas where traditional undersea capacity struggles to reach.

Alternative connectivity options become more attractive when primary infrastructure faces constraints.

Kenya built its reputation as East Africa’s internet hub through reliable, affordable international connectivity. The country hosts major internet exchange points and serves neighboring nations with internet services.

Maintaining this position requires sustained investment in submarine cable infrastructure and backup systems.

CA acknowledged that capacity fluctuations are normal in undersea cable operations. Cables require maintenance, commercial agreements change, and technical issues arise. However, the sharp quarterly decline shows how quickly Kenya’s internet backbone can shift.

More than ever, there needs to be diversified internet routes and stronger redundancy planning. Kenya currently depends heavily on a few major undersea cables. Additional cables and alternative routing could provide more stability when individual systems face problems.

READ: Inside WIOCC’s Vision to Transform Kenya’s Internet Infrastructure

The government and private sector must also coordinate long-term infrastructure planning. Our digital economy grows faster each quarter, but the underlying infrastructure requires years to plan and build.

Today’s capacity decisions will determine tomorrow’s internet capabilities.