Space Safety

23/09/2025

458 views

3 likes

Every day, Earth is bombarded by tiny asteroids and meteoroids, most too small to even be detected. But what if we could study these space rocks by watching their impacts on the Moon? A new ESA project funded under the Horizon Europe programme releases its first observations.

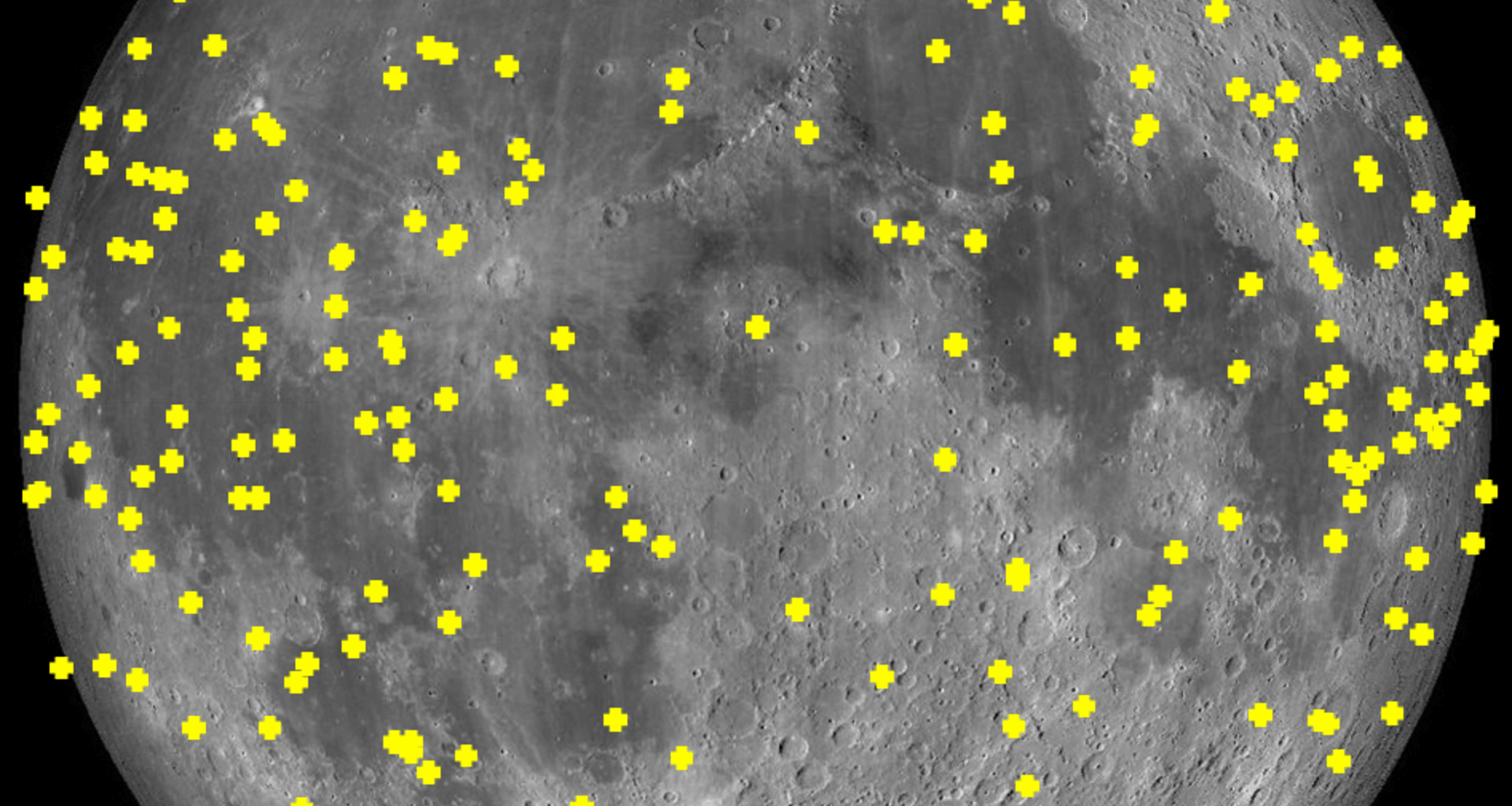

Locations of lunar impact flashes detected by the NELIOTA project

Unlike Earth, the Moon has no atmosphere to shield itself. When meteoroids and asteroids strike its surface, they produce visible flashes that can be captured by telescopes. By analysing these flashes, scientists can estimate the size and mass of the impacting objects, the dimensions of their crater as well as how the temperature evolved upon impact, offering a unique window into the population of near-Earth objects that often go unnoticed.

This is the goal a new project coordinated by the European Space Agency (ESA) and implemented by the National Observatory of Athens: NELIOTA-III (Near-Earth object Lunar Impacts and Optical TrAnsients). The project is fully funded under Horizon Europe, the European Union’s key funding programme for research and innovation, and builds on the success of two previous observation campaigns.

Over the next three years, NELIOTA-III will significantly boost Europe’s ability to detect and analyse lunar impact flashes and fund the development of an open-access Lunar Impact Flash (LIF) database, inviting contributions from the wider scientific community.

First observations and cloudy eclipse campaign

Observation of a Lunar impact flash in August 2025

In mid-August, the NELIOTA team began observations under the new project. During the first four nights of the campaign, five lunar impact flashes were detected but only one was validated due to its detection in both sensors. This flash is the 193rd to be validated since the start of the first campaign in 2017.

On 7 September, a special campaign was planned for the lunar eclipse, which offered a rare opportunity to observe flashes under special conditions. Unfortunately, cloud cover at the telescope prevented observations during the eclipse itself.

Despite this setback, Juan Luis Cano, from ESA’s Planetary Defence Office, said that “this campaign demonstrated the readiness of the system. Now fully underway, ESA and its partners are ready to turn the Moon into a natural laboratory for planetary defence”.

Jumpin’ Jack Lunar Flash

The Kryoneri Observatory – the world’s largest eye on the Moon

Just like its predecessors, the project’s activities take place at the Kryoneri Observatory, which is operated by the National Observatory of Athens and located in Greece.

From there, a 1.2 m telescope has been using two advanced digital cameras to record images of the Moon at a rate of 30 frames per second and in different colour ranges – allowing the temperature of the flash to be estimated. Automated software analyses the video obtained and identifies possible impact flashes.

“With its unique ability to estimate the temperatures of lunar impact flashes and the largest-diameter telescope dedicated to such observations, NELIOTA-III places Europe at the forefront of meteoroid research. We are proud to contribute to this pioneering European effort, helping to advance planetary defence and deepen our understanding of near-Earth objects,” said Dr Alexis Liakos, Associate Researcher at the Institute for Astronomy, Astrophysics, Space Applications and Remote Sensing, National Observatory of Athens.

Beyond lunar observations, the Kryoneri Observatory also served as the site of ESA’s groundbreaking optical communications demonstration campaign earlier this summer. In a remarkable feat of precision, a powerful laser beacon was transmitted from the observatory toward NASA’s Psyche spacecraft, located over 300 million kilometres away, marking a major step forward in deep-space communications.

Like