Every few years, camera companies roll out something meant to grab attention. Sometimes, those ideas turn into revolutions: autofocus, in-body stabilization, and mirrorless mounts all began as risks that paid off. But for every real innovation, there’s a graveyard of gimmicks — features and products that sounded futuristic, won headlines, and then died in obscurity. Here are five of the quirkiest gimmicks that promised to change photography but went nowhere.

These gimmicks tell us something about the times they were born into. Some came from chasing cultural fads, like the 3D craze of the early 2010s. Others were the result of technological dead ends, when companies bet on formats or workflows that seemed clever but collapsed under better alternatives. A few were genuinely imaginative but simply impractical, highlighting the gap between what marketing teams want to sell and what photographers actually need. Looking back, they’re funny, frustrating, and strangely instructive.

3D Cameras: A Dimension Nobody Wanted

The early 2010s were drenched in 3D hype. James Cameron’s Avatar had just made over $2 billion worldwide, and every major electronics brand scrambled to push 3D TVs into living rooms. Camera makers, desperate not to miss the wave, joined the frenzy. Fujifilm led the charge with the FinePix Real 3D W3, a compact with twin lenses that could capture stereoscopic stills and video. The marketing leaned heavily on futurism: imagine your vacation photos popping off the screen in glorious 3D, no glasses required thanks to the built-in lenticular display.

On paper, it was brilliant. In practice, it was clunky. The camera was bulkier than comparable compacts, the image quality wasn’t competitive when you weren’t shooting 3D, and the entire sharing ecosystem was broken. To view 3D properly, you needed either another W3, a specialized monitor, or a 3D TV that almost nobody owned. Even then, the resolution was low, the depth effect was inconsistent, and the whole process felt more like a tech demo than a usable workflow. What Fujifilm sold as the future of photography quickly revealed itself to be an awkward detour.

The downfall of 3D cameras wasn’t just about Fujifilm. Sony dabbled with 3D sweep panorama modes, and Panasonic tried its hand with 3D conversion lenses for Micro Four Thirds. None of them stuck. The issue was cultural as much as technical: while 3D had momentary buzz in theaters, consumers didn’t actually want to relive their lives in stereoscopic form. For everyday photography, like birthdays, vacations, and portraits, the extra dimension added more hassle than joy. Once 3D TVs tanked, the entire ecosystem collapsed, taking cameras with it.

The downfall of 3D cameras wasn’t just about Fujifilm. Sony dabbled with 3D sweep panorama modes, and Panasonic tried its hand with 3D conversion lenses for Micro Four Thirds. None of them stuck. The issue was cultural as much as technical: while 3D had momentary buzz in theaters, consumers didn’t actually want to relive their lives in stereoscopic form. For everyday photography, like birthdays, vacations, and portraits, the extra dimension added more hassle than joy. Once 3D TVs tanked, the entire ecosystem collapsed, taking cameras with it.

Today, the FinePix W3 is a curiosity for collectors and retro YouTubers. It’s remembered less as a serious camera and more as an emblem of how companies chase trends. The irony is that depth-based imaging did find a place later, not in standalone 3D cameras but in computational portrait modes on smartphones. Apple and Google succeeded where Fujifilm failed, but they did it by hiding the complexity and delivering a simple promise: background blur at the push of a button. The lesson of the W3 is that people don’t want new dimensions unless they add something obvious and easy.

Oddball Storage Formats

Before SD cards ruled, storage for digital cameras was a chaotic arms race. Companies tried everything: CompactFlash, SmartMedia, xD cards, even magnetic storage. Sony, famous for its proprietary impulses, leaned on familiar formats like floppies and CDs in its Mavica series. The earliest Mavicas in the late ’90s used 3.5-inch floppy disks, letting you pop them straight into a PC, which was genuinely useful at the time. Later, Sony rolled out versions that wrote to mini CD-Rs, promising huge storage increases and universal compatibility. A few experiments with Minidisc also surfaced, tying into Sony’s audio ecosystem.

The pitch was clever: use media people already knew. In reality, it was a logistical mess. Floppies filled after fewer than 20 images at VGA resolution, and even those took forever to write. The CD-based models added bulk and moving parts that sucked batteries dry, while Minidisc was already struggling to find a foothold outside Japan. Meanwhile, flash memory was getting cheaper, faster, and more compact every year. By the mid-2000s, SD and CompactFlash had completely steamrolled these oddball formats.

The odd storage experiments reflected a deeper truth about the transition to digital: nobody knew what the standard would be. Camera companies hedged bets, hoping to lock users into proprietary systems. Sony, in particular, tried to extend its dominance with formats like Memory Stick, which survived longer but still eventually lost. Consumers, however, gravitated toward simplicity. They didn’t want to juggle fragile CDs or buy overpriced proprietary cards. Once CompactFlash and SD emerged as universal, the battle was over.

Today, Mavica cameras and Minidisc curios pop up on eBay and TikTok, often as punchlines. Enthusiasts buy them for nostalgia or novelty, not serious use. Yet their failures aren’t meaningless. They show how early digital photography wasn’t inevitable: it was messy, fragmented, and full of experiments. Some worked, some flopped. The graveyard of odd storage formats stands as a reminder that the simplest solution usually wins.

Built-In Projectors: The Party Trick Nobody Used

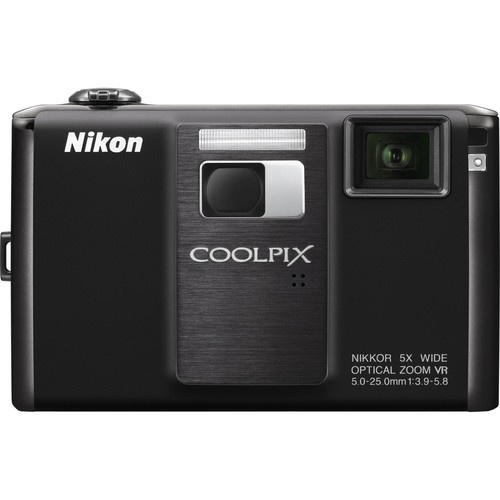

In 2009, Nikon unveiled the Coolpix S1000pj, a compact camera with a built-in pico projector. The pitch was irresistible for marketers: capture your photos and instantly share them by projecting a slideshow on the nearest wall. Commercials showed groups of friends in darkened rooms laughing as their images came to life in movie-theater style. It was framed as a new social way to enjoy photography, something more communal than staring at a tiny LCD.

In reality, the feature collapsed under its own impracticality. The projector was dim, requiring near darkness to be visible. Image quality was muddy, the battery life evaporated after a short session, and the novelty wore off fast. Worse, the timing was disastrous. By 2009, smartphones were rapidly becoming the dominant way to share photos. Instead of awkwardly beaming an image onto a wall, people just pulled out their iPhones and passed them around. What Nikon thought was futuristic already felt dated on arrival.

Nikon doubled down with follow-ups like the S1100pj and S1200pj, but the writing was on the wall. Sales fizzled, and the feature never spread to other lines. The idea of blending projectors into consumer devices had some cultural traction at the time, as Samsung had tried pico projectors in phones, too, but it never solved a real problem. The truth was that social photo sharing had already gone digital, not physical. Projectors were fighting the wrong battle.

Nikon doubled down with follow-ups like the S1100pj and S1200pj, but the writing was on the wall. Sales fizzled, and the feature never spread to other lines. The idea of blending projectors into consumer devices had some cultural traction at the time, as Samsung had tried pico projectors in phones, too, but it never solved a real problem. The truth was that social photo sharing had already gone digital, not physical. Projectors were fighting the wrong battle.

Today, projector compacts are remembered as one of Nikon’s strangest experiments. They’re fascinating in retrospect because they show how desperate manufacturers were to differentiate point-and-shoots in an era when smartphones were eating their lunch. Adding flashy but impractical features was a last-ditch attempt to save a dying category. It didn’t work, but it left behind one of the most memorable gimmicks in camera history.

Wi-Fi Direct Printing Buttons: The One-Touch Nobody Touched

In the mid-2000s, camera makers thought the holy grail of convenience was printing. Rather than transferring files to a computer, you’d press a “print” button on your camera and beam the shot directly to a printer. Standards like PictBridge and Wi-Fi Direct were hyped as the next big step in workflows. Cameras included literal dedicated print buttons, promising one-touch magic. The dream was clear: shoot, press, and hand grandma a glossy photo in seconds.

The reality was slow and frustrating. Printers that actually supported the standards were rare, setup was clunky, and even when it worked, it took ages. By the time you finally had a print, the spontaneity was gone. Worse, the cultural shift was moving in the opposite direction. People were printing fewer photos, not more. Sharing had moved online, first to Facebook and Flickr, later to Instagram and TikTok. A button for direct printing became a button nobody touched.

The deeper problem was that this wasn’t solving the right problem. What users wanted was frictionless sharing, not awkward printing. Smartphones nailed this almost immediately: snap a photo, tap share, and it was online for everyone. Cameras with print buttons completely misjudged the direction of culture. Instead of making photography simpler, they exposed just how disconnected manufacturers were from the way people actually used images.

By the early 2010s, print buttons quietly vanished. Most people don’t even remember they existed. They stand as proof that chasing “ease of use” doesn’t mean much if you’re solving a problem people don’t actually have.

Sony QX Lens-Style Cameras: The Awkward Hybrid

In 2013, Sony unveiled perhaps the strangest attempt to bridge smartphones and dedicated cameras: the QX series. The Sony QX10 and QX100 were essentially lenses with sensors built inside that clipped onto your smartphone. The concept was radical: pair your phone’s screen and connectivity with real optics and larger sensors. The QX100 in particular borrowed from the RX100, promising near-compact quality in a pocket-sized hybrid. For a brief moment, the tech press hailed it as genius.

But using it was a nightmare. The wireless connection lagged, pairing often failed, and holding a phone with a lens dangling off the front felt precarious. Ergonomics were atrocious, the app interface was slow, and battery life was laughable. Even when the QX100 delivered good files, the friction of getting them was enough to kill the joy. Smartphones were evolving so fast that within a few years, their built-in cameras were good enough to rival what the QX promised, without the hassle.

The QX experiment was bold but misguided. It assumed people wanted to bolt extra gear onto their phones when, in reality, the whole appeal of a phone is that it’s self-contained. Instead of making photography easier, the QX made it awkward. Sony quietly discontinued the line, moving on to strengthen its RX and Alpha ranges, which were better suited to competing on their own terms.

The QX experiment was bold but misguided. It assumed people wanted to bolt extra gear onto their phones when, in reality, the whole appeal of a phone is that it’s self-contained. Instead of making photography easier, the QX made it awkward. Sony quietly discontinued the line, moving on to strengthen its RX and Alpha ranges, which were better suited to competing on their own terms.

Today, the QX is remembered as both weird and fascinating. It showed that even when companies have brilliant engineering, they can still misjudge user behavior. The smartphone-camera gap was never going to be solved by hybrids. Instead, it was solved by the relentless progress of phone cameras themselves. The QX stands as a symbol of that transition: clever, ambitious, but ultimately obsolete before it even had a chance.

Conclusion: Innovation or Gimmick?

Each of these gimmicks promised a future that never arrived. It’s easy to laugh at them now, but they reveal something important: camera makers don’t fail because they lack imagination. They fail when their imagination isn’t aligned with how people actually use cameras. Gimmicks aren’t just about bad engineering they’re about bad assumptions. And while these products went nowhere, they still matter, because they remind us that innovation is messy, risky, and full of dead ends. Every failed gimmick leaves behind lessons that shape the successes that follow.