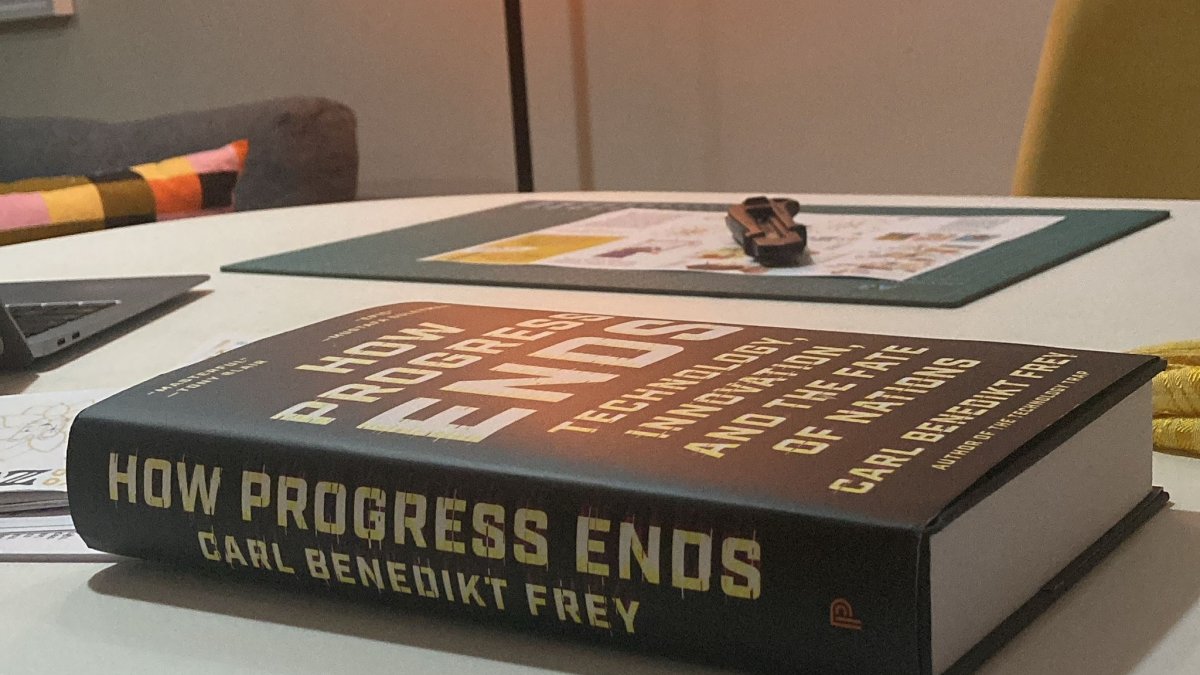

Soren Kierkegaard once remarked that life is “lived forwards but understood backwards.” Carl Benedikt Frey, in “How Progress Ends,” invites us on precisely such a backward-looking journey at a moment when the future seems most uncertain. At a time when artificial intelligence dominates our conversations, he leads us into an extended meditation on the nature of change, innovation and novelty itself. His journey takes us across geographies, centuries and social experiences – reminding us that we urgently need this broader horizon.

The age of AI presupposes, after all, a system vast enough to model not only present realities but also to draw upon the accumulated experiences and wisdom of the past. Perhaps, in this new era, humanity may finally reclaim insights long overlooked – fragments of knowledge that, across centuries, were set aside or forgotten. This is what renders Frey’s ambitious itinerary so compelling: it reframes inherited wisdoms in light of today’s dilemmas and insists that progress can only be understood when the past is brought into dialogue with the present.

For years, I had grown weary of books that rehearse familiar tropes about the “rise of the West” and the supposed “stagnation of the East.” These narratives, whether triumphalist or elegiac, strike me as both repetitive and inadequate. What we need is not another civilizational scoreboard, but a way of examining history through its institutions, periods and events: bureaucracy, war, autocracy – phenomena too often reduced to caricature, moralized or dismissed. Their misplacement in the intellectual map has long obscured the larger picture. In this respect, “How Progress Ends” came as a relief. It manages, without lapsing into vertical political correctness, to put distant and disparate human experiences into dialogue, grounded in evidence rather than ideology, and to render them in a form both comprehensible and compelling.

One of the most striking passages concerns the role of social networks in sustaining or frustrating innovation. “The importance of social networks for innovation is no mystery,” Frey writes, invoking the sociologist Mark Granovetter’s demonstration that much innovation arises from networks rich in “weak ties.” Progress, in this account, depends less on heroic individuals than on the texture of connections through which knowledge circulates.

History, he suggests, makes the point all the more vivid. The arrival of Turkish coffee in Europe produced more than a taste for a new stimulant: It created new spaces of exchange. The coffeehouse, as Frey reminds us, became a “public laboratory of exchange,” one where merchants, philosophers and officials mingled in an atmosphere conducive to intellectual ferment. In contrast, in America, where taverns and saloons dominated, such venues “did not nurture the same innovation-friendly environment.” The same beverage, in other words, gave rise to radically different cultural forms.

This attention to micro-histories is what gives the book its distinctive force. Frey moves easily from macroeconomic cycles to granular anecdotes, from the collapse of Soviet central planning to the conversations of London coffee drinkers, without ever losing sight of the central claim: progress is not inevitable. It can stall, reverse, or emerge in surprising places.

The book’s historical range is broad. Wars, for example, appear not merely as interruptions of development but as accelerators of invention. The Crimean War, the Korean conflict and the arms race of the Cold War all furnish examples of technologies and organizational practices born of crisis rather than peace. Bureaucracies, too, are rescued from caricature: sometimes obstacles to invention, at other times its midwives.

What distinguishes Frey’s analysis is its resistance to both liberal triumphalism and authoritarian apologetics. The United States, he argues, now faces a crisis of innovation; China, far removed from liberal orthodoxy, has built a system that delivers sustained growth. Neither model is presented as exemplary. Instead, both remind us that institutional design is never final and that societies revisit their choices cyclically, sometimes reversing course entirely – as with the repeated privatization and nationalization of Britain’s railways.

The final chapters turn toward artificial intelligence. Here again, Frey avoids deterministic narratives. Adaptation to AI, he suggests, depends on institutional flexibility and cultural disposition. Some societies will integrate it rapidly, while others will do so more hesitantly, and outcomes will vary accordingly.

Here, too, Kierkegaard’s dictum resonates. We live forward into an AI-saturated future, but understanding what it means requires looking backward – recovering the neglected wisdoms and forgotten contingencies of history.

Frey demonstrates what Hannah Arendt once described in a different context: “The day after a revolution, even the most radical revolutionaries become conservatives.” This line, which he cites approvingly, captures the paradox that every breakthrough sows the seeds of its own domestication.

“How Progress Ends” is, ultimately, not a pessimistic book but a chastening one. It asks us to relinquish our illusions of inevitability and instead attend to the fragile mechanics of innovation – networks, institutions and cultures – that shape human futures. In so doing, Frey has written a study that is both historically grounded and urgently contemporary, a book to be read forward, understood backward and annotated along the way.

The Daily Sabah Newsletter

Keep up to date with what’s happening in Turkey,

it’s region and the world.

SIGN ME UP

You can unsubscribe at any time. By signing up you are agreeing to our Terms of Use and Privacy Policy.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.