Canadian entrepreneurs are building the future—they just aren’t building it in Canada. A new study warns the country’s startup scene failed to recover post-pandemic, with Canadian-educated founders increasingly creating jobs elsewhere. The authors blame rising domestic friction and call for cultural and financial incentives to reverse the trend. But the report overlooks the biggest hurdle to startups—and the jobs they create: Canada’s real estate addiction.

About The Study

Today we’re looking at a study on Canadian startups. Leaders Fund, a VC firm focused on early-stage enterprise software, analyzed 2,932 venture-backed companies that raised at least US$1M between 2015 and 2024. The firm’s report serves as both a public analysis and an internal market check, drawing its data from Specter—a startup database tracking more than a million companies worldwide.

Startups are a critical but underappreciated growth engine in advanced economies. An OECD study found that while startups make up just 20% of firms, they generate 50% of new jobs. They also drive innovation and productivity—two areas where Canada lags badly, with the Bank of Canada calling the latter a national “crisis.”

High-profile tech scandals have left many Canadians wary of the industry. But the rise of AI means nearly every problem will soon be a tech problem. As former BoC governor Stephen Poloz told us, the rise of advanced automation means a third of workers may need retraining by 2030. Canada can either build the solutions here, or fall behind while resisting the inevitable.

Canada Squandering Its Talent: Fueling Job Creation Abroad

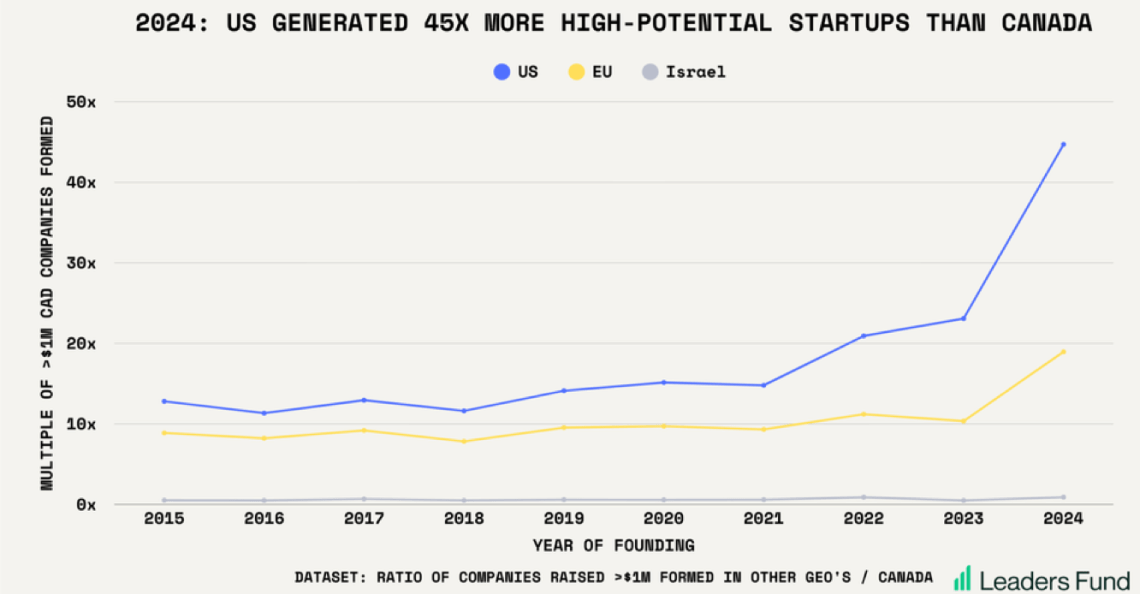

Canada’s share of high-potential startups is collapsing. In 2015, it produced 1 for every 11 in the US; by 2024, the ratio had fallen to 1 for every 45. Over the same period, Canada’s global share dropped from 4.3% to 1.5%, while the US and Israel gained further ground.

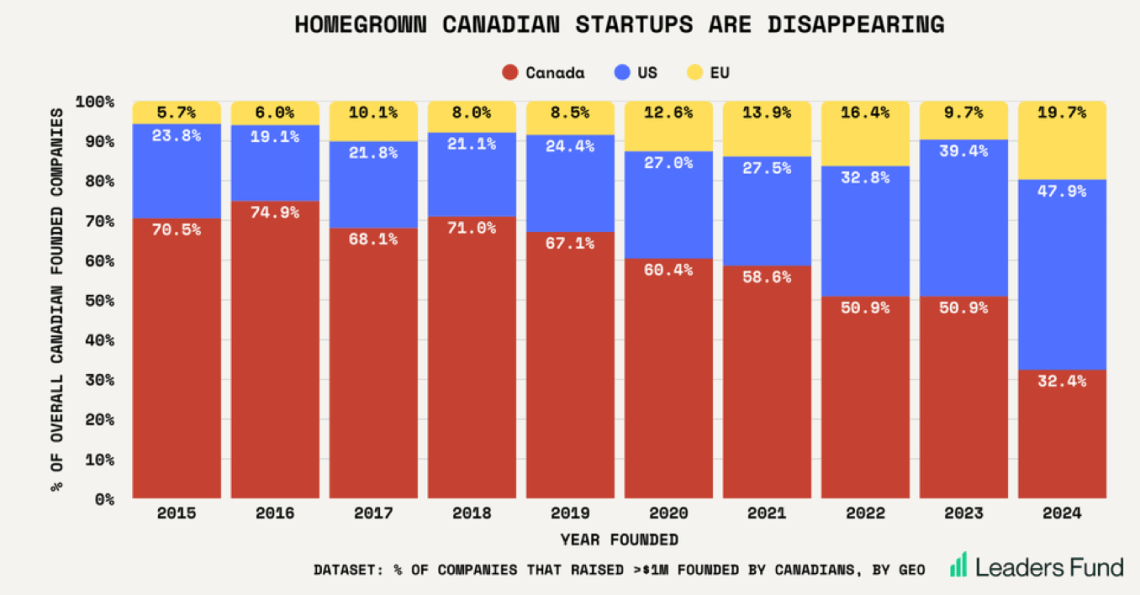

The problem isn’t a lack of talent. Canada trains and attracts some of the top talent in the world—they’re just building companies abroad, where they experience fewer barriers to traction. Fewer than a third (32%) of Canadian-educated founders launched in Canada, while nearly half (48%) went to the US—with the report noting those companies raised twice as much capital, scaled faster, and achieved a higher success rate.

Canada spends billions cultivating talent but fails to keep it. The result: taxpayers subsidize the growth engines of competing economies. How did Canadians end up financing the rope and wood to build the gallows for their own economy?

Canadian Startups Struggle To Bounce Back From The Pandemic; Targeted Policies Needed

The study identified Canada’s pandemic recovery as a key turning point. “Our restrictions and lockdowns were among the longest in the world. At the same time, the rise of remote work lowered the barriers to relocating, and the US became the main beneficiary,” the report notes. The report adds: “…what began as a temporary shock has left a lasting drag on our innovation economy.”

To reverse the shift, the report calls for cultural changes and broader policies—not just incentives for the largest, best-connected firms. Recommendations include a Canadian version of the US Qualified Small Business Stock program, allowing shareholders in small businesses to pay 0% capital gains on exits if held for more than 5 years. This would create direct incentives for founders, employees, and investors—at minimal cost to taxpayers.

The report also points to international models. Israel’s “buy blue” campaign encourages domestic tech adoption through pride and tax incentives; a Canadian “buy red” strategy could do the same. China’s “mass entrepreneurship and innovation” approach targets resources to encourage competition, rather than backing a few state-endorsed winners. That’s right—China’s communists are better at capitalism than we are these days.

Finally, the report stresses the need for cultural changes: letting founders shape policies that affect them and celebrating Canadian ambition to counter the country’s tall poppy syndrome.

Despite the relative simplicity of these solutions, the report overlooks one of the biggest hurdles to startups: real estate.

Canadian Real Estate: An Underdiscussed Risk To Domestic Startups

Canada’s obsession with real estate doesn’t just starve entrepreneurship—it’s a drag on housing itself.

Startup hubs like Toronto and Vancouver are increasingly out of reach for young adults, especially post-pandemic. Soaring shelter costs leave less disposable income for spending, meaning fewer customers for startups. It also means less risk-taking—an important issue since successful startup founders tend to be in their early 40s, the same age Canadians finally scrape together a down payment for their first home. Are tax perks and cultural praise really enough to cover a first home, a first company, and a family—all at once? Hardly an ideal window to build a startup.

Decades of policy have hardwired real estate as a safer, more rewarding bet. Why back a risky startup when tax and finance policy tip the scales toward property investment? Even banks are warning that rate cuts intended to boost business investment are at risk of being swallowed by housing speculation.

You Might Also Like