Open Architecture has risen quickly to become one of China‘s most influential studios and is now set to curate a major exhibition in Sydney. In this interview, married founders Huang Wenjing and Li Hu explain their unusual approach.

Since establishing its Beijing office in 2008, Open Architecture has developed a reputation for experimental buildings that often look like something else altogether.

Open Architecture founders Huang Wenjing (left) and Li Hu (right). Photo courtesy of Open Architecture

Open Architecture founders Huang Wenjing (left) and Li Hu (right). Photo courtesy of Open Architecture

“People come to us, normally they are not quite sure what they want, but they know they want something different, something special,” Li told Dezeen.

“If a client wants a specific style, it’s kind of boring to us. We want to push the boundary, do something different, something we’ve never done before.”

The studio’s recently completed Sun Tower (top video) is a 50-metre-tall concrete cone that functions like a giant sundial. Li explained that it originated from the broadest of instructions from the client.

“We are more interested in a project that is a question,” he said. “We worked on a lot of projects with very simple briefs.”

“For Sun Tower, the brief was to make something substantial. We enjoy the process of helping the client to define the project.”

Open Architecture is designing the opening exhibition for Powerhouse Parramatta, due to open late next year. Photo by Rory Gardiner with Colby Vexler

Open Architecture is designing the opening exhibition for Powerhouse Parramatta, due to open late next year. Photo by Rory Gardiner with Colby Vexler

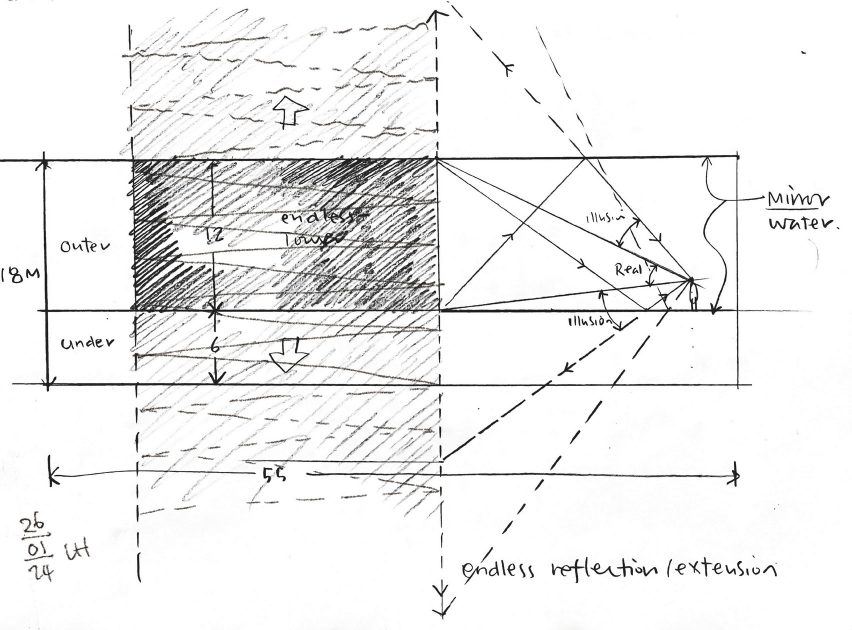

This was also the case for Task Eternal, the opening exhibition at the under-construction Powerhouse Parramatta in Sydney, due to open in late 2026.

The announcement was made by Powerhouse Museum today that Open has been commissioned to design and curate the exhibition – an aerospace showcase informed by Ted Chiang’s science-fiction short story The Tower of Babylon.

It will be presented in Ps1, the largest museum space in Australia measuring more than 2,100 square metres and 18 metres in height.

Li and Huang were approached by Powerhouse Museum to help shape the ambitious project.

Usually a studio would be given a brief and object lists before diving into the exhibition-design process, but Open did not receive any brief from Powerhouse Museum. Instead, they worked collaboratively with the in-house curatorial team to come up with the initial concept.

Open’s concept for Task Eternal aims to prompt visitors to consider humanity’s expansionist tendencies. Image courtesy of Open Architecture

Open’s concept for Task Eternal aims to prompt visitors to consider humanity’s expansionist tendencies. Image courtesy of Open Architecture

“It’s literally a museum within a museum,” Li said. “We really want to push the form of exhibition making, combining architecture, concept and curation.”

The expansive and immersive exhibition will invite visitors on an ascending journey through four acts — Skyward, Power, Off-Earth and The Return.

Open structured the exhibition based on the experience of watching a film, in which they created 35 different scenes for the four main acts, from early navigation stories, to the commercialisation and weaponisation of space, to exploring space and then returning to Earth.

Their hope is that Task Eternal will encourage visitors to reflect on the human urge to strike out into the unknown.

“There’s so much we don’t know, but there’s a lot more we need to hold on to. That is the Earth, where we are grounded,” said Huang.

The exhibition will take place within the biggest museum space in Australia. Photo by Rory Gardiner with Colby Vexler

The exhibition will take place within the biggest museum space in Australia. Photo by Rory Gardiner with Colby Vexler

The exhibition is the latest example of Open moving beyond the landmark design it is known for, with Huang and Li believing is necessary adaptation in a complex and changing world.

“We are less arrogant than we used to be, humbled by how fast things can change,” said Huang.

“The way to cope with the changing world is to learn more skills, do more things, explore more territories so we can always adapt. In Chinese, we call it ‘skill in 18 types of combat’,” she added.

“China is making a clear statement about its status in its architectural expression”

The studio has recently taken on a housing project in Shenzhen, a typology it has never tackled before. As well as the architectural design, it is also taking on the planning, landscape design, interior design, lighting design and furniture design for the project.

“Ironically when the real estate market in China was doing so well in the past 20 years, we almost had no opportunity of doing housing design,” said Huang.

“But now since its collapse we started to get opportunities, because people realise the market is flooded with bad products of residential buildings, and put more emphasis on lifestyle and quality of life.”

Named Nanshan Commune, the project is intended to be an antidote to the ubiquitous gated communities and residential towers in China.

Chapel of Sound, a concert hall near Beijing, is one Open’s best-known projects. Photo by Jonathan Leijonhufvud

Chapel of Sound, a concert hall near Beijing, is one Open’s best-known projects. Photo by Jonathan Leijonhufvud

Open has sought to take advantage of the sloping site, introducing four green terraces and two community centres to the ground level.

“We believe buildings are to protect nature, not destroy nature,” said Huang. “Architecture should be an instrument to capture the invisible elements of nature, such as light and sound, to ignite our senses to feel the surroundings, because we, as humans, are part of nature.”

“This understanding of nature is embedded into our work, where we build, how we build, where we choose not to build, how to build the nature into the city and how to build into the nature, and what materials to use,” she claimed. “Every single decision reflects our attitude to nature.”

The duo attempted to convey these ideas in the form of a documentary film, called Nature Trilogy, produced in collaboration with director Zhang Nan and premiered at Venice Architecture Biennale earlier this year.

It profiles three of Open’s best-known projects – UCCA Dune Art Museum, Chapel of Sound and Sun Tower – and the philosophy that connects them.

Documentary film Nature Trilogy premiered at Venice Architecture Biennale earlier this year. Image courtesy of Open Architecture

Documentary film Nature Trilogy premiered at Venice Architecture Biennale earlier this year. Image courtesy of Open Architecture

China takes a different approach to sustainability than the West, the pair argue, pitching it as a nature-oriented understanding rather than a technical understanding.

“Nature is not about numbers – how much carbon emissions, how much energy used,” said Li. “You can have a building that is beautiful on the chart, but does not perform. Ecology is a social agenda, not a technical calculation.”

“As architects, we have a lot of professional training on how we understand sustainability and how to implement technology from a scientific perspective, but we also need to consider the social and spiritual aspects,” added Huang. “Nature is sacred. Our ancestors see nature as power and mystery, but nowadays, we see it as resources, something we can use and control.”

“Those other dimensions should take more critical importance, otherwise we end up with more technology to treat the problem we created by technology. We need to treat the source of the problem, not the symptoms,” she continued.

The video is by APCRstudio Han Yuheng.

Dezeen In Depth

If you enjoy reading Dezeen’s interviews, opinions and features, subscribe to Dezeen In Depth. Sent on the last Friday of each month, this newsletter provides a single place to read about the design and architecture stories behind the headlines.