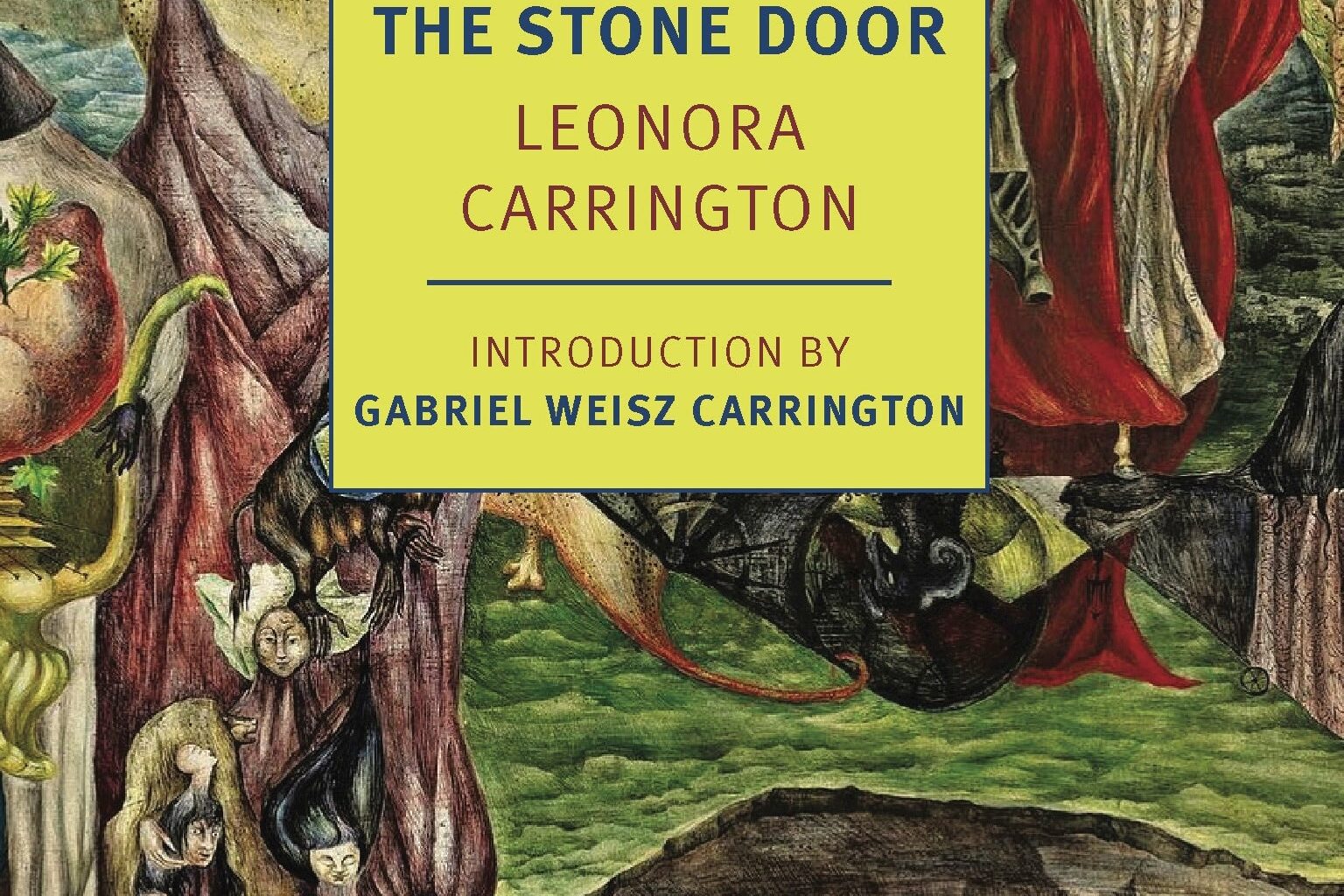

Leonora Carrington

The Stone Door

NYRB, 2025

In Leonora Carrington’s The Stone Door, the unnamed narrator traverses Mesopotamia in search of the cryptic King of the Jews. As she walks across the land of the dead, she meets an ancient elf-like being who is made almost entirely of clay. He retreats from a mass of “human pottery” that is not quite dead but not completely undead and as he runs towards her, one of his feet falls off “like a dry leaf from a tree.” The mystical being asks the narrator if she is a slave who has come from “Bagdad.” Somewhat insulted, the narrator responds, “Why, no… I am a beggar.”

Recently reissued by NYRB, Carrington’s first novel is replete with parables, images, and epigrams that amount to thought-provoking puzzles, resulting in a kaleidoscopic adventure that curlicues and unfurls unto itself, not unlike shuffling a deck of painted tarot cards or toying with a seemingly endless Matryoshka doll. As such, The Stone Door does not follow a conventional plot, but blends genres like autofiction, fantasy, and magical realism in search of the enchanted portal at the heart of the novel: the stone door of kescke. Guarded at turns by a crucified giant parrot, and later trapping a mysterious, spritely woman with long hair, the illusive stone door gives the narrative its unifying throughline, brimming with a prophecy that spurs its zigzagging plot. But in the rare instances the stone door does appear, it materializes like a dreamlike image. Flickering from the shadows, it always begs more questions than answers: “The stone door is closed against me, let me in, Oh my Love, let me in.”

For Carrington, the inspiration behind her surrealist paintings and fantasy novels—including the better known and more satirical The Hearing Trumpet—sprang from the gray area between the sleeping subconscious and wakeful knowledge. The notion that dreams are a site of witness, or a point of access to another reality, appears in the beginning of The Stone Door, when Amagoya, a young woman living in a house in Mexico, comes across the diaries of the narrator who has visited the land of the dead. Amagoya learns that the nameless narrator walked through Mesopotamia in a “dream, memory or vision,” implying that commiseration with ghosts or astral projection into netherworlds lies in the subliminal consciousness.

As such, The Stone Door is roughly divided into three parts: Amagoya’s journeys with and learning of the occult, the stream-of-consciousness narrative of the mysterious woman trapped in the land of the dead behind the stone door, and a bildungsroman recounting the story of Zacharias, a young Jewish child who is dropped off by his mother to a boarding school in Budapest, where he and other students are identified by a number. A fascinating interval midway through the novel focuses on Phillip and Michelle, a couple who are Amagoya’s friends and neighbors. As they cook dinner, Phillip recalls the time he cooked a pest-like baby dragon after it jumped out of a book in the library of the British Museum. “I cooked it in a cream sauce and the taste was rather like that of a squid,” Phillip said. “A squid is really more of a reptile than a fish.”