Art

Portrait of Daniel Day-Lewis and Ronan Day-Lewis on the set of Anemone. Photo by Maria Lax / Focus Features. © 2025 Focus Features, LLC. All Rights Reserved. Courtesy of Focus Features.

Ronan Day-Lewis first started drawing at two years old. Using an Etch A Sketch, he repeatedly sketched motorcycles—like the one his father had—before erasing the screen and starting over again. This obsession, over time, transformed into his current ethereal landscapes, which are now on view in “Anemoia,” at Megan Mulrooney in Los Angeles through November 1st. Making art has always been a way of “cycling through obsession,” Day-Lewis told me at Kellogg’s Diner in Williamsburg, the New York neighborhood he’s lived in for the past three years. “It’s hard to remember when I realized that painting was something I wanted to pursue seriously, because there was never a question for me.”

Ronan Day-Lewis, installation view of “Anemoia” at Megan Mulrooney in Los Angeles, 2025. Courtesy of Megan Mulrooney.

Day-Lewis’s last name carries weight, though his parents, the Oscar-winning actor Daniel Day-Lewis and filmmaker Rebecca Miller, went out of their way to shield him from Hollywood’s glare. He spent many years, from the age of 7 to 13, in rural Ireland before moving to New York for high school, and eventually attending the Yale School of Art. Yet, film still held a draw for him. Today, at 27, his career is on the rise in both arenas: On September 28th, Anemone, which stars his father in the leading role, premiered at the New York Film Festival, and he’s already booked another solo exhibition next year at Nino Mier in Brussels. The focus of Day-Lewis’s work in both media is memory: how it slips and reappears like an image drawn and erased.

Painting inspirations from nostalgia

Ronan Day-Lewis, installation view of “Anemoia” at Megan Mulrooney in Los Angeles, 2025. Courtesy of Megan Mulrooney.

The word “anemoia,” meaning “nostalgia for a time you didn’t experience,” came to Day-Lewis while scrolling through Instagram Reels. One video in particular—a “nostalgia edit” that stitched together archival footage of 2000s-era classrooms and other half-familiar scenes—caught his attention. The images weren’t his own, but they carried a strange, borrowed intimacy. The caption beneath it, explaining the definition of anemoia, offered an idea that stayed with him. The idea dovetailed with his painting practice, where he takes inspiration from Flickr images from the early 2000s for his figures and landscapes. He called the photographs “mysterious snapshots of people’s lives that were mundane but also had this loaded narrative potential.”

The specific look of early digital flash photography—where “everything is sort of hyper-flattened”—reminded him of his own childhood photos. In three works all entitled What we did and where we did it (The Big Gloom) (2025), for example, spectral figures recline in violet light holding strings of glowing bulbs across their bodies, while a central panel depicts a clouded sky above anonymous rooftops. Like the borrowed images that inspired it, the piece drifts between dream and memory, staging a nostalgia that belongs to someone else. His use of lurid, washed-out colors makes the scene appear temporary; whether it’s fleeting or decaying is up to the viewer.

Many of his paintings feature similarly lustrous, dreamlike landscapes. This inspiration traces back to his childhood, particularly the months he spent in Marfa, Texas—when his father filmed There Will Be Blood (2007)—where the desert “embedded itself” in his consciousness. Day-Lewis also cited his time on Prince Edward Island, where his parents filmed The Ballad of Rose and Jack (2005). These terrains impressed on him what he calls “an interest in landscape as an emotive force,” places carrying both the “melancholy” and “sublime.” He looks for this evocative landscape everywhere, even citing Ang Lee’s Hulk (2003) poster with its metallic green and stormy sky as a reference he returned to for his painting show.

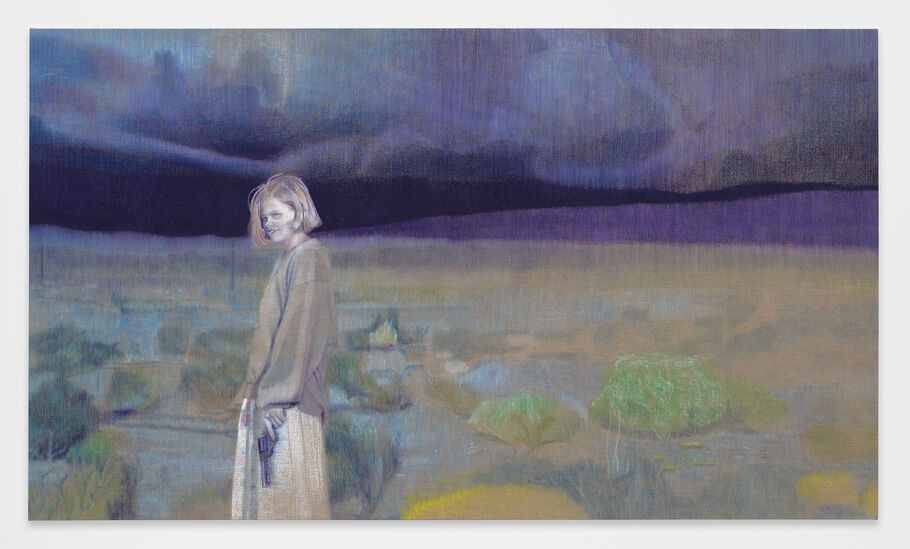

This sensibility underpins works like That Was Then and This Is Now (Death, the Maiden) (2025), a painting he long envisioned as “a teenager with a gun staring down a storm in the desert.” Unable to stage or find an exact source image online, he stumbled on a ’90s album cover showing a girl with a gun that captured the “exact feeling” he wanted. He spliced the image onto a desert landscape to create his source image. The result is a haunting portrait of the gun-wielding girl in front of a foreboding, hazy landscape.

The environment is intended to convey to the audience the emotion of the figures, a technique he also applied to his first film, where the landscape is “responding directly to the emotional trajectory of the characters,” he explained.

Anemone and working with his father

Portrait of Ronan Day-Lewis with actors Daniel Day-Lewis and Sean Bean during the production of Anemone. Photo by Maria Lax / Focus Features. © 2025 Focus Features, LLC. All Rights Reserved. Courtesy of Focus Features.

Anemone (2025) began with a loose idea: Ronan Day-Lewis wanted to write about brothers, as one of three. The project took shape after he began talking with his father. Coincidentally, Daniel, who announced his retirement from acting in 2017 after Phantom Thread, had been mulling over the same idea. In 2020, the two started bouncing ideas off each other, eventually landing on the premise of a man living in self-imposed exile whose estranged brother (played by English actor Sean Bean) arrives unannounced after 20 years apart. “There was this intuitive rhythm [my father and I] fell into where we had sort of a shorthand,” said Ronan Day-Lewis.

Ronan and Daniel first conceptualized Anemone as a mostly silent film, where the landscapes do the emotional heavy lifting—much like Ronan’s paintings. Anemone fills the spaces between dialogue with images of distant, vicious storms and lingering bird’s-eye views of a bustling, verdant forest.

“Being inside the film took certain elements that were already in my work as a painter—like the narrative leanings and the more cinematic aspects of it—and pulled them naturally more to the forefront,” he said. Ronan reuses images from the film in his painting, too: a dead fish carcass drifting in a body of water, seen in Wisdom (2025) at Megan Mulrooney, resurfaces in one of Anemone’s final scenes.

Day-Lewis’s work circles memory from every angle—paintings made of borrowed snapshots, a film probing dark corners of the psyche—all asking the same question. As Day-Lewis put it, his work depicts “the way the present is constantly being metabolized into the past.”

MR

Maxwell Rabb

Maxwell Rabb (Max) is a writer. Before joining Artsy in October 2023, he obtained an MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and a BA from the University of Georgia. Outside of Artsy, his bylines include the Washington Post, i-D, and the Chicago Reader. He lives in New York City, by way of Atlanta, New Orleans, and Chicago.