A familiar tone turns into phantom dialling. The little box in your house or office is calling out to an answering modem. Brief chirps confirm the two devices are ready to talk each other’s language. More beeps: binary code in audio form. Then, a teeth-grinding fuzzy sound, shards of digital noise pushed through your landline. A brave new world loads slowly on the screen in front of you.

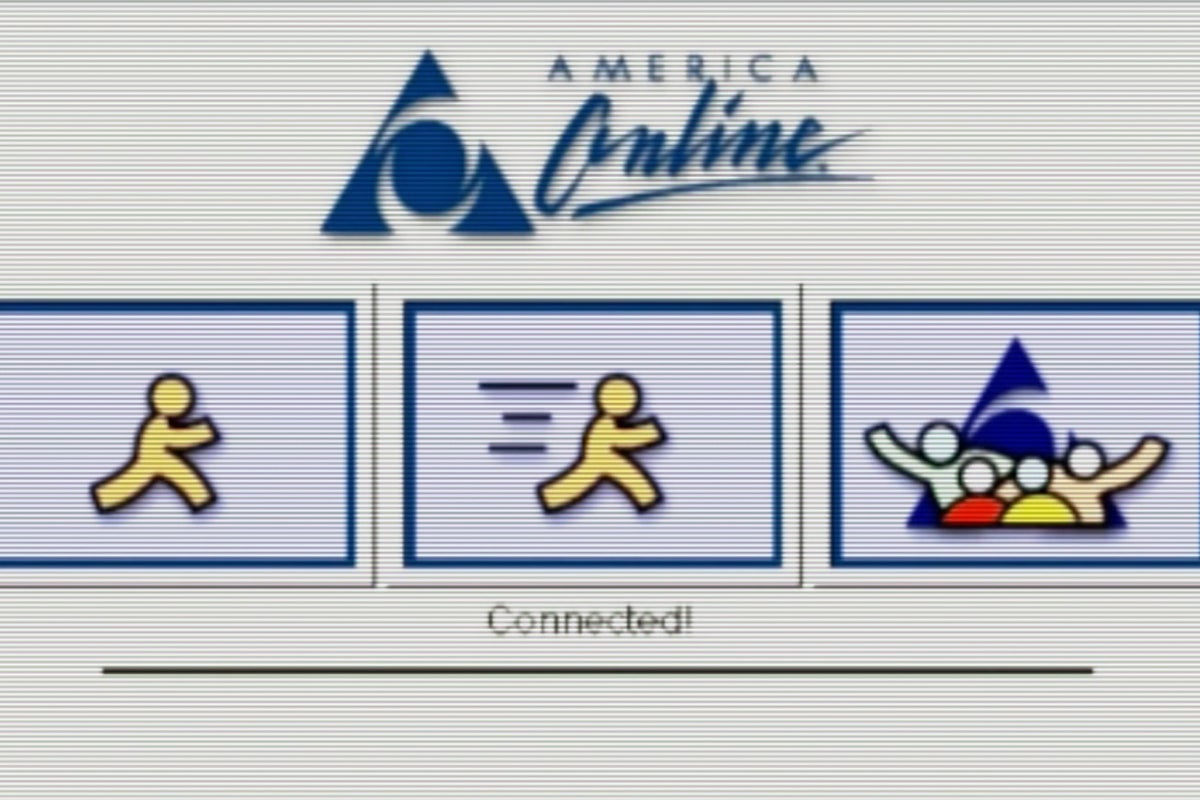

The familiar icon of an AOL pyramid connecting and the sound of the dial-up handshake, often followed by someone in the other room shouting: “Get off the internet, I need to use the phone!” Or “it’s taking a bit longer because America is waking up”.

Dial-up internet and the era it represents – patchy connections, “You’ve got mail!” and an upstart tech industry – has been finally laid to rest. As of this week, AOL – the most popular internet service provider of the late 1990s – has finally discontinued its dial-up service, severing the connection of around 175,000 Americans who still (apparently) are using it.

Most of the world said goodbye to dial-up a long time ago. Most of us live in an age of seamless and relentless connection – neither sleep nor death will stop your phone from pinging with updates. But the story of dial-up is a vital one to understand and could even set the tone for the future.

It certainly can help us parse the chaos of today’s internet-infused reality, as well as what comes next, be it AI chatbots overpowering Google search, an Elon Musk monopoly, or the destruction of the internet entirely.

Back to the future

It was late evening in 2020 when Dr Gough Lui spied a familiar beige box crammed in the corner of his office – an old computer. “I live and breathe technology,” the biomedical and electronics engineer from Western Sydney University tells me, “I decided to adopt it for a nostalgia trip.”

After a bit of tinkering, he recreated a dial-up connection. “Part of the charm was simply the fact we had to be patient,” he remembers. Flaky connections and dropouts were tolerated, simply put, “because it was worth it”.

There has been a noticeable nostalgia for the early internet era lately. The breakneck speed of tech has led to a fondness for a quieter, more comfortable time. The recently opened Nokia Design Archive in Aalto University, Finland, invites people to reminisce about a time of brick phones and before push notifications. The Barbican’s extremely popular emo exhibition “I’m Not Okay: An Emo Retrospective” celebrated “a transatlantic subculture that thrived in cyberspace”.

Trends in fashion and on social media suggest that even younger generations are looking back fondly at a time they may not have experienced first hand. Y2K fashion is hitting catwalks and high streets again. TikTok is awash with explorations of old tech-y visual aesthetics, retroactively named things like “Frutiger Aero” (rolling green fields and bright aquatic PC backgrounds) and “Utopian Virtual” (the old art style of educational CD-ROMs and Microsoft Encarta).

open image in gallery

Pandora’s PC: the hardware is chunky by today’s standards, but the machines allowed people access to a burgeoning world (Getty/iStock)

Colette Shade, author of Y2K (How the 2000s Became Everything), has noticed this nostalgic longing. “Millennials have a sense memory of dial-up … Getting the internet installed at your house was a formative experience for many people that age, especially in retrospect.”

But more than this, the idea of “going online” is something that younger generations have not experienced; the internet wasn’t “woven into every aspect of life”.

“You could go online and talk to friends and strangers but then log off and go outside,” she says. Maybe it’s not the Nokia 3310 and low-rise pants we miss from the time, maybe it’s the prospect of living unplugged from the incessant din of the modern tech world. But how did we get here? Where did dial-up come from?

You’ve got mail…

In 1966, a telephone line connected a TX-2 computer in Massachusetts manned by MIT researcher Lawrence Roberts to a Q32 computer on the other side of the country in California, manned by Tom Marrill. The reason for this connection? Like many technological innovations, it was the American military-industrial complex.

US president Dwight Eisenhower had created the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) 11 years earlier to contend with Soviet Union tech. Working on ballistic missiles and nuclear defences required a network for ARPA computers. Thus, that connection was created.

What was the first message sent using the internet? “LO”. It was meant to be “LOGIN”, but the network crashed.

If the biblical language was incidental, ARPA colleagues Robert Taylor and his boss JCR Licklider would make a prediction that would change everything on God’s green Earth: “In a few years, men will be able to communicate more effectively through a machine than face-to-face.”

It would be people like Barry Shein and Peter Dawe who would help fulfil this far-fetched prophecy.

Shein has a lofty and dystopian-sounding title: CEO of The World – the first internet service provider for the public. “I had installed the internet at Boston University over several years,” Shein tells me. Many of his customers were former students or recently laid-off Bostonians, who had developed a taste for email and the growing discussions happening online.

In 1989, Shein hired a lease line from UUNET, put five modems on a bookshelf and created something like the personal internet subscription we know today. The internet – and the widening web available via the connection – was no longer just for students or workplaces.

Dawe’s business started with similar grandeur at Pipex, the first UK internet service provider that operated a 64k transatlantic lease line to the US. Dawe hired a line from BT, rented a windowless Cambridge office, a PC and a secondhand Astra, and started offering connections to companies.

open image in gallery

AOL, the front-runner of commercial dial-up in the early Noughties, has discontinued their dial-up service (Getty/iStock)

These first forays were met with slight disinterest and sometimes scandal. “There almost immediately appeared an opinion that I was illegally reselling a government resource,” Shein explains of The World’s early days. “At the time, I estimated we were blocked from about one-third of the internet, but there was still plenty for our customers to access.”

The pushback was commercial as well. Networks were “walled gardens”, Dawe explains. “The business model was to lock you in … But we were happier being promiscuous, and that was a massive innovation.” In 1993, the BBC signed up for a lease line. Pipex expanded abroad, and by the time he had moved on to found the Internet Watch Foundation, he maintains it was responsible for “half of global internet traffic”.

In 2000, 30 per cent of the US had a dial-up connection, the phone-hogging method was the primary pathway online as the digital superhighway was evolving. But as time pressed onward, broadband – with its faster connection and higher frequencies freeing up phone lines – began to surge, and its gain was dial-up’s loss. A decade later, only 5 per cent of Americans were using it to get online.

What comes next?

The “Magnificent Seven” companies born from the data-centred era after dial-up now make up 35 per cent of the US stock market. The “hippiedom” that Dawe says ran through those early years has been replaced. Innovation and huge amounts of capital walk in lock-step.

Despite rising murmurs of a “bubble” and the ever-receding horizon of human-level computer intelligence (AGI), AI is still the tech sector’s big thing. Its disruptiveness, combined with the “ens***tification” of search engines could mean that we talk about Google much like we’re talking about dial-up now, in a few years – or sooner.

Gigabit internet is the super-speedy connection that much of the hopes of AI are pegged to. For you, it means faster internet – it was rolled out to 3,800 homes in Northumberland this year – for the tech overlords, it means “quantum computing”, a complex kind of technology that borrows scientific notions of “entanglement” and “superpositions” to (potentially) solve big issues in pharmaceutical development and engineering.

The achievement of all of this still requires a connection to the internet, and on that, Dawe has his dark predictions. “Starlink is a fly in the ointment” when it comes to the free market of connection. Elon Musk’s company provides satellite internet services, and Dawe says it could grow to monopolise internet connections.

open image in gallery

The Jaguar Land Rover cyber attacks are a harrowing warning about putting our trust in newer technology (AFP/Getty)

The other issue is the shift towards cloud computing. It works, Dawe says, until it doesn’t. Internet outages were reported in the Middle East and Asia at the start of this month, linked to Red Sea cables being “cut”, according to Microsoft. Governments in countries affected were fairly quiet on the events, but in an increasingly polarised world where vital infrastructure is in the aether of the cloud, one can only imagine what a larger outage could do.

The recent cyber attacks on Marks & Spencer, The Co-op and Jaguar Land Rover could be a horrifying portent. All three companies outsource to Tata Consultancy Services (TCS) for a range of tech needs, including – at least for The Co-op – adopting a “cloud-first strategy”.

If all of this sounds a little frantic and entropic, media theorist and author Geert Lovink agrees, and he’s had enough.

“Things are finite, and that is in contradiction to Silicon Valley and its need for eternal growth,” he says. His radical 2022 text, Extinction Internet, purports the need for a detachment from this seamless connection, to overcome the “polycrisis” we face, along with an understanding of the new techno-social dimension of the mind, and how it has been saturated by all-you-can-scroll content, delivered via a seamless internet connection.

He’s quick to point out that the cost of the internet has stayed the same since the days of The World and Barry Shein, but everyone pays it with no complaints.

And for what? For that dial-up promise of “people connecting” and a democratised cyberspace to be lost in a haze of chatbots and politically noxious social media platforms? Or for tech-libertarians to make money off of our cyberspace psyches while we are left with smartphone addictions and emaciated attention spans?

The first message on the internet may have had a biblical tinge, but the first ever message sent via electronic communication – Samuel Morse and his telegraph in 1844 – was a direct Bible quote: “What hath God wrought?” It feels more apt by the day.