Now that the Trump administration has taken an equity stake in domestic mining company Lithium Americas, it’s a safe bet the United States will continue to stray from traditional market capitalism for the foreseeable future. As to why we’re going down this road, the most common answer is—along with Jonah Goldberg’s accurate (IMO) view of the president’s motivations—that this new “American state capitalism” is a response to China’s version of the same. Chinese industrial policies, so the theory goes, have quickly moved the country from an economic nuisance (albeit a large one) to an existential threat, dominating various industries and all but demanding the U.S. government adopt similar policies—subsidies, tariffs, equity infusions, and more—just to keep up. The new Lithium Americas deal follows this script to the letter.

Readers of Capitolism know that, while I agree certain Chinese policies and their effects raise real challenges that demand serious policy responses, the bipartisan approach to countering Chinese state capitalism with American state capitalism is flawed on multiple levels. Most obviously, we’re not China: Policies that might “work” in a still-developing autocracy with 1.4 billion people won’t necessarily “work” here in our smaller, wealthier, messier democracy, and Washington has plenty of untapped alternatives proven to produce desired results at a much lower fiscal, economic, and social cost.

Recently, however, another rather important flaw has emerged: Chinese industrial policies aren’t even “working” over there—maybe even for the industry that’s supposedly their biggest success story.

China’s EV ‘Success’

A big problem with industrial policy—in China, the United States, or anywhere else—isn’t that it never produces a globally competitive “winner” company or industry, but that it will typically produce far more “losers” and do so at a great cost. As we discussed in 2023, research has shown this to be the case in China, too, with failures greatly outnumbering success in key industries like aircraft and semiconductors and accompanied by broader economic harms—resource misallocation, corruption/graft, overcapacity, financial instability, etc.—that “hinder rather than accelerate China’s economic development.”

Stay Ahead of the Curve With Dispatch Energy

The Dispatch’s newest weekly newsletter will dive into the politics, policy, and innovation shaping America’s energy future, presented by Pacific Legal Foundation. Featuring a rotating roster of contributors who are experts in their respective fields, each edition will feature incisive analysis on everything from oil and gas and permitting regulations, to renewables, climate, and the grid.

At that time, EVs were one of the apparent successes countering the standard industrial policy critique, and the Chinese industry—led by oft-discussed BYD—continues to be a point of pride for fans of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and/or industrial policy in general. As economist (and Chinese industrial policy expert) Lee Branstetter explained at that time, however, there were grounds for both optimism and concern about China’s EV experiment:

Despite the high costs and instances of fraud associated with EV industrial policies, the rapid growth of the sector and its success at competing with leading Western firms in the home market and elsewhere suggests the benefits of government intervention may outweigh the costs… But a full accounting of the costs and benefits of industrial policy is not yet possible, because the massive wave of entry induced by these generous subsidies has come at a real resource cost. If the vast majority of these producers fail and much of the production capacity thereby created has to be liquidated, and if the profit margins of the survivors are razor-thin, then the cost-benefit calculation could appear very different over the next few years.

Since then, the costs have become more apparent. As has been widely reported, the last few years have seen a massive bout of policy-driven overcapacity in China’s EV sector and supporting sectors like batteries with almost 130 different brands—and a big web of increasingly desperate local dealers—engaging in a brutal and cost-oblivious battle for market share. The result has been a “price war panic” that has collapsed profits and challenged many firms’ financial viability.

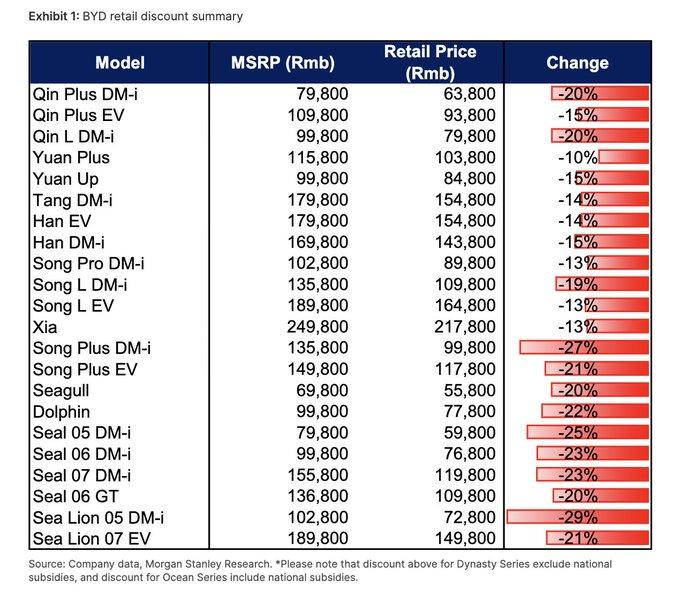

In response, the Chinese government has embarked on an “anti-involution” campaign to stop destructive practices in the industry, even going so far as to summon major EV producers to Beijing “to address concerns about the long-running price war”—a rare move that, per Bloomberg, “shows how much scrutiny the nation’s top leadership is paying to the sector, amid concerns the price war is becoming unsustainable and could send weaker companies into bankruptcy.” While industry leader BYD has remained profitable, it has drastically cut prices to pressure competitors:

While industry analysts believe that only 15 to 20 of the 120-plus brands now in China will ultimately survive the “bloodbath,” they also agree that—even as Beijing tries to cut government support for EVs—many of the very same Chinese industrial policies that caused the country’s overcapacity problem will prevent it from concluding any time soon:

[L]ook closer at the industry and the picture is not pretty. Already, fierce competition among automakers has gotten ruthless, with about 50 automakers fighting for customers by slashing prices again and again. Manufacturers facing ruinous losses are struggling to pay the companies that supply their parts. And yet they keep borrowing from state-run banks to build more factories, leading to extensive overcapacity…. Beijing is struggling to contain the industry’s overall capacity in part because the state-owned companies refuse to shrink to offset the growth of the private companies making so many electric and hybrid vehicles. Closing state-owned factories that make gasoline-powered cars and laying off their workers is politically difficult, especially in a high-profile industry like automobiles. Beijing is concerned partly because banks are potentially exposed to heavy losses if automakers and their parts suppliers cannot pay their bills. As big employers in an industry that is the pride of China, automakers have the clout to make sure that others keep financing their losses. And banks have been under regulatory mandates to lend for clean energy technologies.

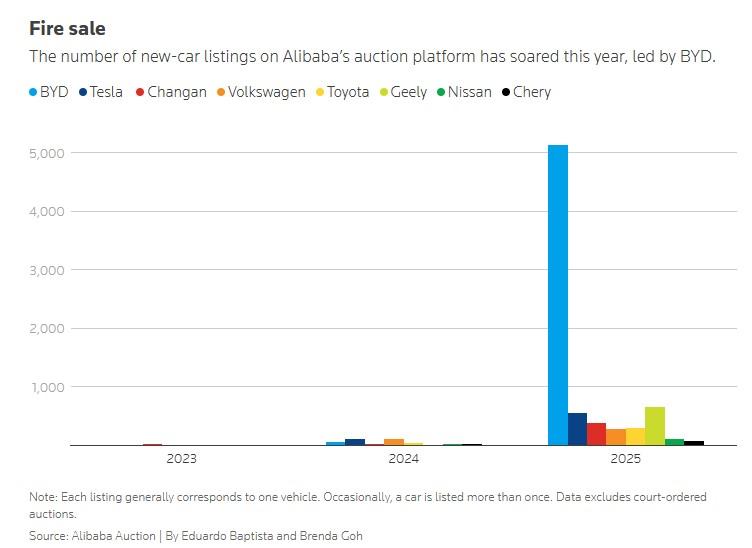

Provincial governments, desperate to hit CCP growth targets and replace tax revenue lost by China’s property bust, also continue to provide “deep financial support for lossmaking groups,” further prolonging China’s automotive overcapacity problem—and the waste it’s generating. A new, must-read Reuters dive into the industry, for example, finds that Chinese government policies have not only created twice the production capacity the country needs and perverse incentives impeding reform, but also hordes of cheap, junky models nobody wants. Thousands of new cars have thus popped up on social media and auction sites, with many getting no takers:

Unwanted cars also need somewhere to go. Thus, China now has massive fields of “weedy car graveyards” where many never-driven “zombie” cars have been stashed. And, Reuters adds, “Local governments have strained to clean up abandoned-car lots, which consume land and create environmental hazards.” (For some great visuals, check out this older Bloomberg piece on the issue.)

As the American Enterprise Institute’s Jim Pethokoukis recently put it, “China’s auto industry is becoming a monument to the pitfalls of industrial policy”—not one of its greatest success stories.

The Broader Economic Costs

The obvious counter to these and other hidden costs—including the stuff not produced in China because finite resources were wasted on “zombie” EVs parked in weedy graveyards—is that BYD and a couple other Chinese brands are (so far, at least) leaders in the global EV market and poised to dominate it in the future. Other observers, it should also be noted, are more optimistic about China’s domestic automotive industry in general, seeing any current struggles as a small blemish on a much larger success.

Even so, it would remain the case that EVs are at best an exception to China’s industrial policy rule. As already noted, deep dives into other government-supported sectors—from Branstetter and others—reveal a Chinese government picking many more losers than winners, with supported companies and state-owned champions performing worse than their more market-oriented counterparts in China and still years behind the technological frontier (i.e., where the United States typically is). Just this week, for example, Bloomberg reported that Chinese tech champion Huawei’s most advanced AI chip “can only offer 6% the performance of Nvidia’s next-generation VR200 superchip,” while others doubt Huawei’s products are even as good as Nvidia’s scaled-down “H20″ chip. (One reason why is that Huawei must use Chinese-made chips that are well behind what Nvidia’s products use, thanks to the latter enjoying “a collaborative effort by the whole western community and industry.” Lessons abound!) Even Chinese industries that are globally successful often have problems similar to those facing EVs—or, as this recent Financial Times dive into China’s solar industry documents, even worse issues.

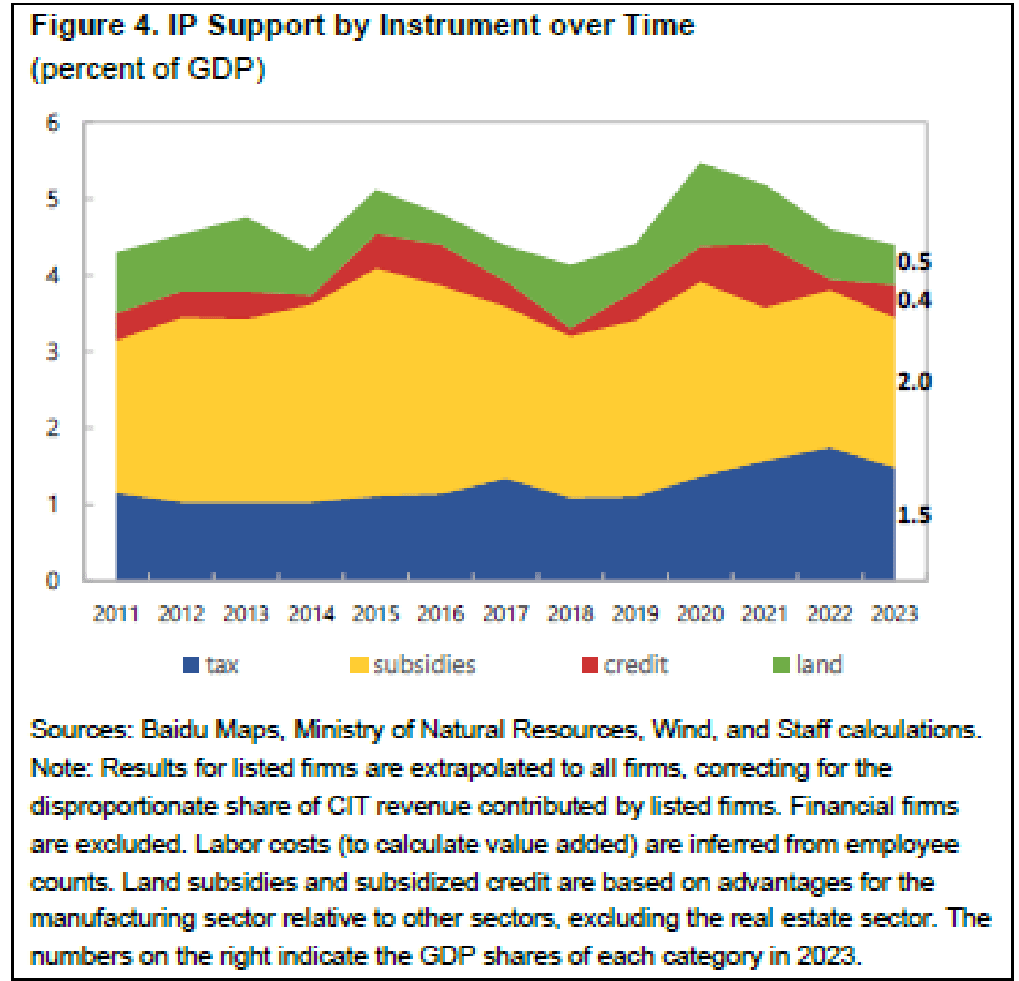

Then there are the broader economic costs arising from China’s state capitalist model—costs that new International Monetary Fund (IMF) research reveals to be mind-bogglingly large. As simply a budgetary matter, the paper estimates that the “equivalent fiscal cost of industrial policy through cash subsidies, tax benefits, subsidized credit, and subsidized land for favored sectors (including both private and state-owned firms)” was annually around 4 percent of China’s GDP between 2010 (when Chinese industrial policy really cranked up) and 2023. Overall, that would mean government spending of around $7 trillion over the period examined—a price tag, the authors note, that could be an understatement due to the other, less-visible government support provided to favored companies.

The IMF paper also finds that, by distorting the allocation of resources in China, industrial policy was a significant drag on national productivity (“total factor productivity” —basically, how much economic output labor and capital collectively generate) and thus China’s economy overall:

Subsidies are associated with excess production relative to a no-distortions benchmark, while trade and regulatory barriers limit production, possibly by increasing the market power of incumbents. Overall, factor misallocation from IP is estimated to reduce domestic aggregate TFP by about 1.2 per cent relative to a no IP baseline, and this channel could reduce the level of GDP by up to 2 percent.

As the Financial Times notes, “Even for an economy like China, foregoing 2 per cent of GDP a year is meaningful”—especially since the IMF notes that this GDP hit should be considered the “lower bound” of the possible damage.

Annually losing 2 percent of your national GDP might not sound like a lot, but it most definitely is. The World Bank estimates, for example, that China’s GDP (in current U.S. dollars) was around $18.2 trillion in 2023, so two extra percentage points would have added $364 billion to China’s economy that year alone. Adding up the losses over the entire 13-year period, meanwhile, puts the costs (again) into the trillions: around $3.4 trillion in lost economic output without compounding and more than $5 trillion with it. Put another way, if the CCP hadn’t embraced industrial policy around 2010, China’s economy would today be around 29 percent larger (at $23.6 trillion!) than it is today—and much closer to the United States ($27.7 trillion in 2023) in terms of its global economic power.

The IMF’s findings could be an outlier in terms of the size of China’s economic losses, but many share the report’s general conclusion that Chinese industrial policy has been costly. A separate 2025 report from the Rhodium Group, for example, finds that China’s signature industrial policy initiative, “Made in China 2025” did indeed have some “consequential successes” in creating self-sufficient and globally competitive industries, including in EVs. The paper adds, however, that “China remains far from achieving its intended self-sufficiency,” and that most of the industries targeted by the initiative—including aerospace, advanced semiconductors, and medical goods—aren’t at or near the global technological frontier. And they acknowledge that the successes came with significant unintended consequences, including a serious hit to economic growth, sagging domestic demand, and major trade tensions abroad:

China’s industrial policy ecosystem has led to profound waste, as local governments piled in with duplicative and inefficient projects. Over the past decade, total factor productivity growth has stagnated and overall economic growth has slowed as the government struggles to transition the economy to a more sustainable model. The emphasis on industrial policy has also contributed to a stall in broader economic reforms, straining relations with China’s key partners. Beijing’s systemic bias toward supporting producers over households or consumers has created a growing imbalance between domestic supply and demand, especially in sectors like automotives, EV batteries, and legacy semiconductors. This industrial overcapacity has contributed to a rapidly expanding trade surplus, intensifying friction with China’s trading partners and adding pressure to its innovation and industrial ecosystems. At the same time, local governments are grappling with the mounting fiscal costs of these policies, forcing difficult trade-offs in their expenditures and further exposing the economic strains of this approach.

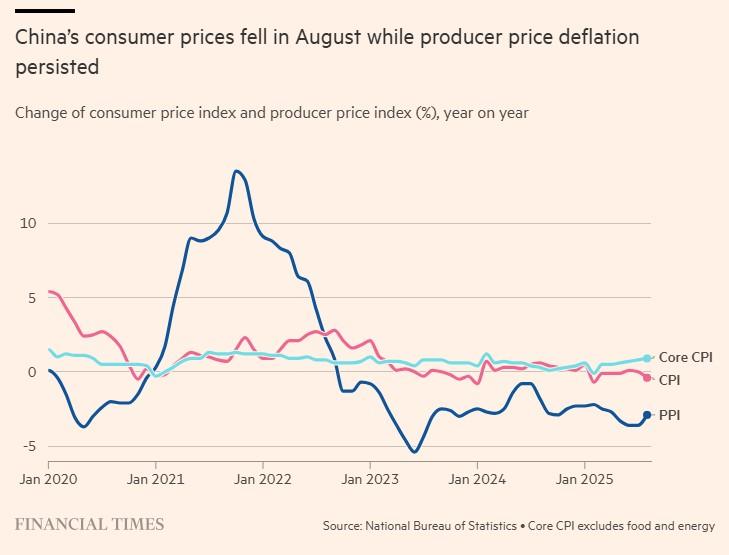

These systemic problems persist to this day and extend far beyond the EV ecosystem—despite myriad Chinese government reform efforts. As the FT reported in late July, “over-dependence on manufacturing investment has taken on new urgency as its excess capacity and weak domestic demand lead the country into one of its longest periods of deflationary pressure since the 1990s.” And the problem has continued since then:

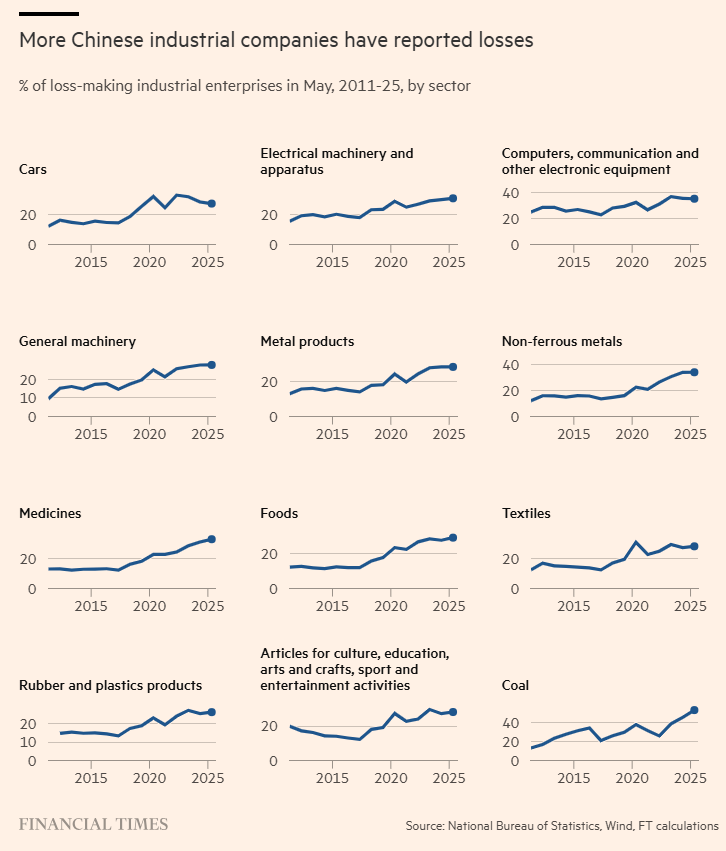

Broad losses in China’s manufacturing sector, the July FT report shows, are also piling up:

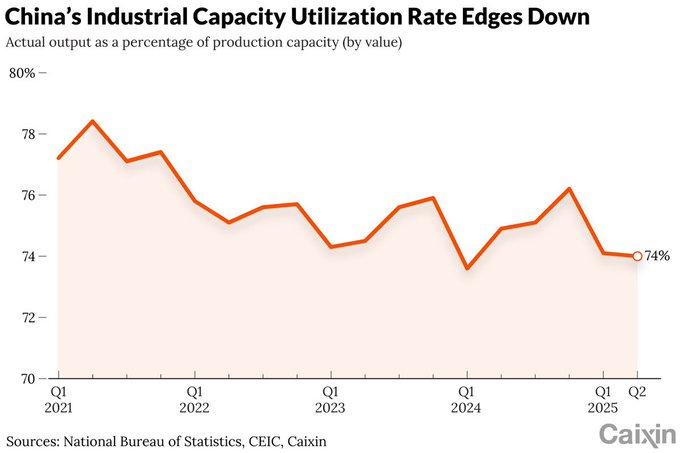

And industrial capacity utilization continues to trend down:

The Chinese government is clearly aware of these broader problems and has tried to get Chinese manufacturers to tighten up and Chinese consumers to spend more. So far, however, the government’s efforts don’t seem to be paying off, and the nation’s “addiction to manufacturing” might instead be getting worse:

But with China’s investment in manufacturing still rising at a blistering pace — up 7.5 per cent this year after a 9.5 per cent rise in 2024 — there is no end in sight. Yan Se, assistant professor in the department of applied economics at the Guanghua School of Management in Peking University, said at a recent seminar that China’s share of global manufacturing value-added could rise to 40 per cent in the next five years, from about 27 per cent now.

As with EVs, Chinese industrial policies and local government dependence on “unproductive investment” to meet growth and tax targets are a big part of the problem. As one Chinese researcher told the FT, “Even with considerable excess capacity, local governments are ramping up industrial and infrastructure investments to counteract weakness in the property market.” And, just like the IMF and Rhodium reports showed, there was a close connection between these “misallocated” investments and lower productivity—a result directly contrary to one of Chinese industrial policy’s main goals.

Another impediment to reform, the Wall Street Journal adds, is that China’s overcapacity problem is no longer limited to “upstream sectors dominated by state-owned enterprises” that take direction from the government. This time around, “Beijing is facing a more broad-based supply glut that has extended to downstream sectors including green tech and consumer goods”—sectors dominated by private companies less responsive to state mandates. Beijing also faces pressure to insulate its economy from U.S. tariffs and to prevent major job losses that could undermine stability. Thus, Bloomberg reported over the summer, a weak job market and rising worker protests have forced Beijing to “keep unprofitable firms alive to save jobs and avoid unrest”—even though doing so runs counter to their overcapacity and deflation priorities.

Even China’s traditional safety valve—exports—has challenges. Leaving aside that the nation is struggling with deflation despite record exports and a record trade surplus, some foreign governments—not just the U.S.—are bristling at all those cheap goods flooding into their markets:

Pressure on China is also very likely to build abroad too. Developed markets are already resisting, but the interesting new development is the raft of trade defence measures being put in place by emerging and middle income countries, for whom China is a large or even the largest trade partner. These include Mexico, Turkey, Brazil, India, South Africa, Vietnam and Thailand. Several now fear premature deindustrialisation as Chinese imports threaten — for example — steel, textiles, and autos.

As we discussed last year, the best economic response to cheap Chinese imports is in many cases to send Beijing a “thank you” note, but there are some legitimate reasons for governments to act otherwise. (New Chinese restrictions on EV exports indicate that the CCP understands this tension quite well.) Regardless, these kinds of trade disputes are—as I noted years ago—a classic industrial policy risk that can further undermine the policies’ efficacy and economic growth more broadly. Coupled with China’s domestic problems, in other words, it’s all par for the course.

Summing It All Up

None of this means China’s economy is collapsing tomorrow. And if forced to steel-man China’s industrial policy, I’d say that, for a developing country with a checkered history and serious need to project international legitimacy, the economic and geopolitical benefits of cultivating a few global winners were worth the massive fiscal and economic costs needed to achieve those wins. I still find this justification weak because the true costs of Chinese industrial policies aren’t anywhere close to clear or contained, and because we simply have no idea what kind of bigger, wealthier, more stable, and less disliked “Counterfactual China” might have emerged without them. (Using the IMF figures, this other China would be almost as wealthy as Poland on a per capita basis—right on the cusp of being high-income, but with 1.4 billion people.)

Regardless, even the steel-manned argument for Chinese industrial policy has little relevance for the United States—a country that, when China first embarked on its big industrial policy push 15-plus years ago, was already big, wealthy, popular, and sitting at the technological frontier in multiple advanced industries (where it continues to sit today). Even if we could afford Chinese industrial policy (we can’t) and had the coercive mechanisms to implement and stick with it (we don’t), there remains no good reason for us to even try, especially when—as already noted—we could be enacting proven policy reforms and leaning into our own comparative advantages instead.

And that conclusion holds before you see the mess that China’s “state capitalist” economy is today.

Chart(s) of the Week

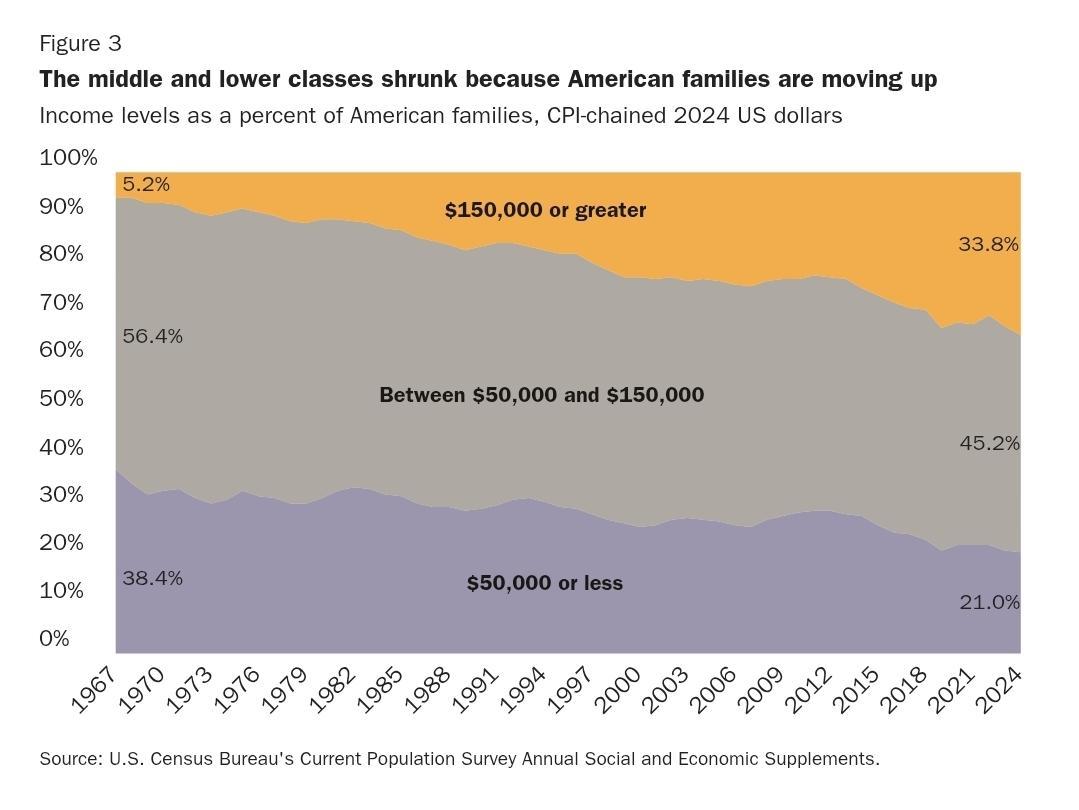

Hooray, the middle class is shrinking!

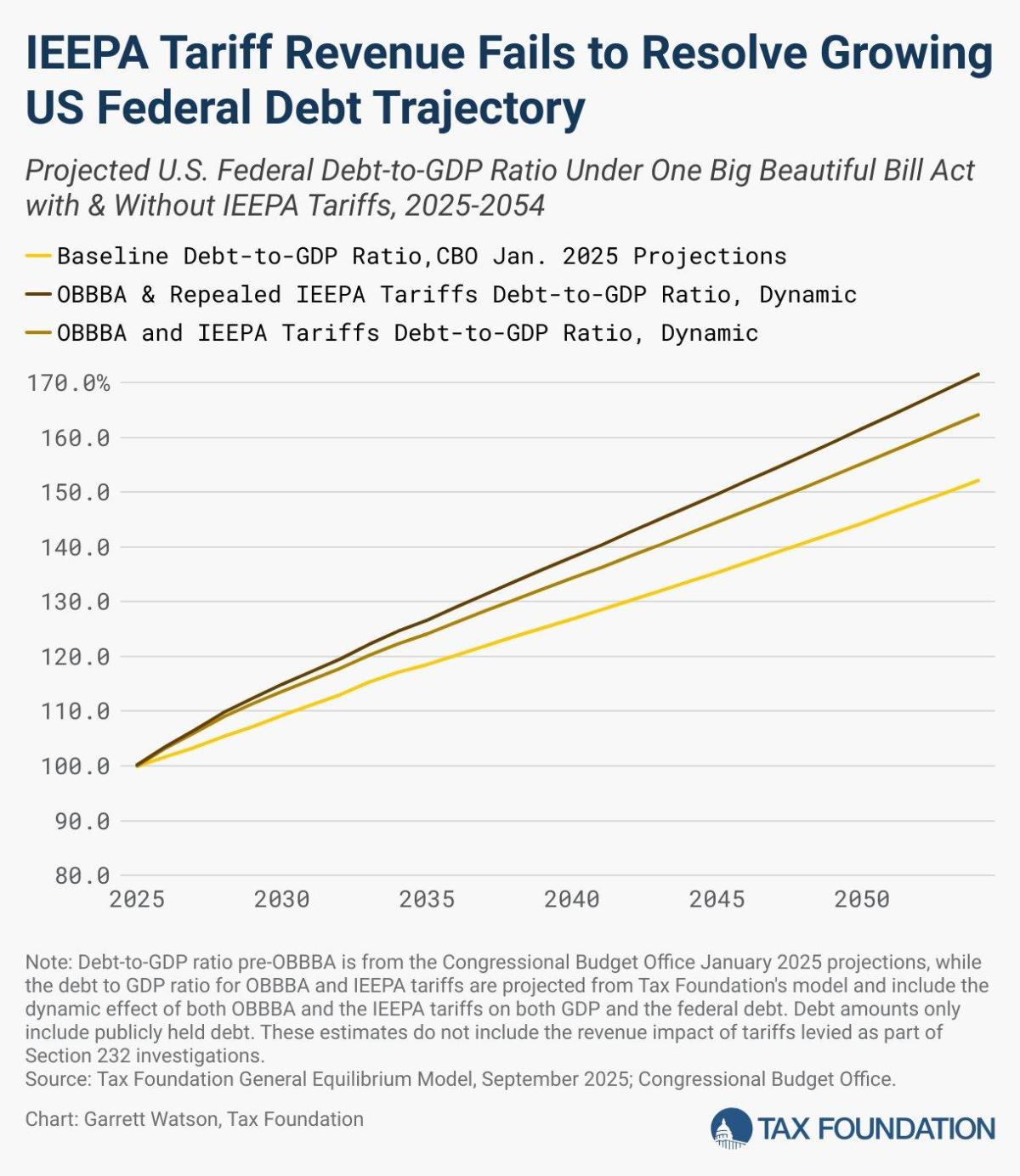

Tariffs do little to fix the U.S. public debt problem (more)

The Links

South Korean trade deal in doubt

Only a small share of permits have been approved for Los Angeles fire rebuild

Retailers quietly passing on tariff costs

Wall Street bets on tariff refunds

Zillow tells us where CPI rent is going (eventually)

Tariffs crush small businesses

“China’s new K visa beckons foreign tech talent as US hikes H-1B Fee” (related)

SHOCK: tariff carve-outs proliferate

Australia displaces U.S. in China’s beef market

U.S. manufacturers oppose robot/machinery tariffs

Vegas workers disappointed by “no tax on tips”