More than six centuries ago, a resident of southern Spain either took off or lost a rough sandal woven from grasses and twigs. Such a shoe normally would decompose over time. But when a bearded vulture picked it up and carried it back to a nest in a cave, something different happened.

The cool, dry air of the cave preserved the shoe perfectly. There it stayed, tucked among branches, as generations of vultures carefully maintained the nesting site—all the way to the present day.

Between 2008 and 2014, scientists rappelled down cliffs to reach a dozen bearded vulture nests and begin analyzing what was inside them. They discovered that shoe, along with more than 200 other human artifacts, including some from the Middle Ages. These finds are described in a new study in the journal Ecology.

Analyzing more human-made and natural objects preserved in vulture nests could give researchers new insight into human history, as well as the history of the ecosystem that safeguarded them through time.

(Africa’s vultures are disappearing. A series of disasters could follow.)

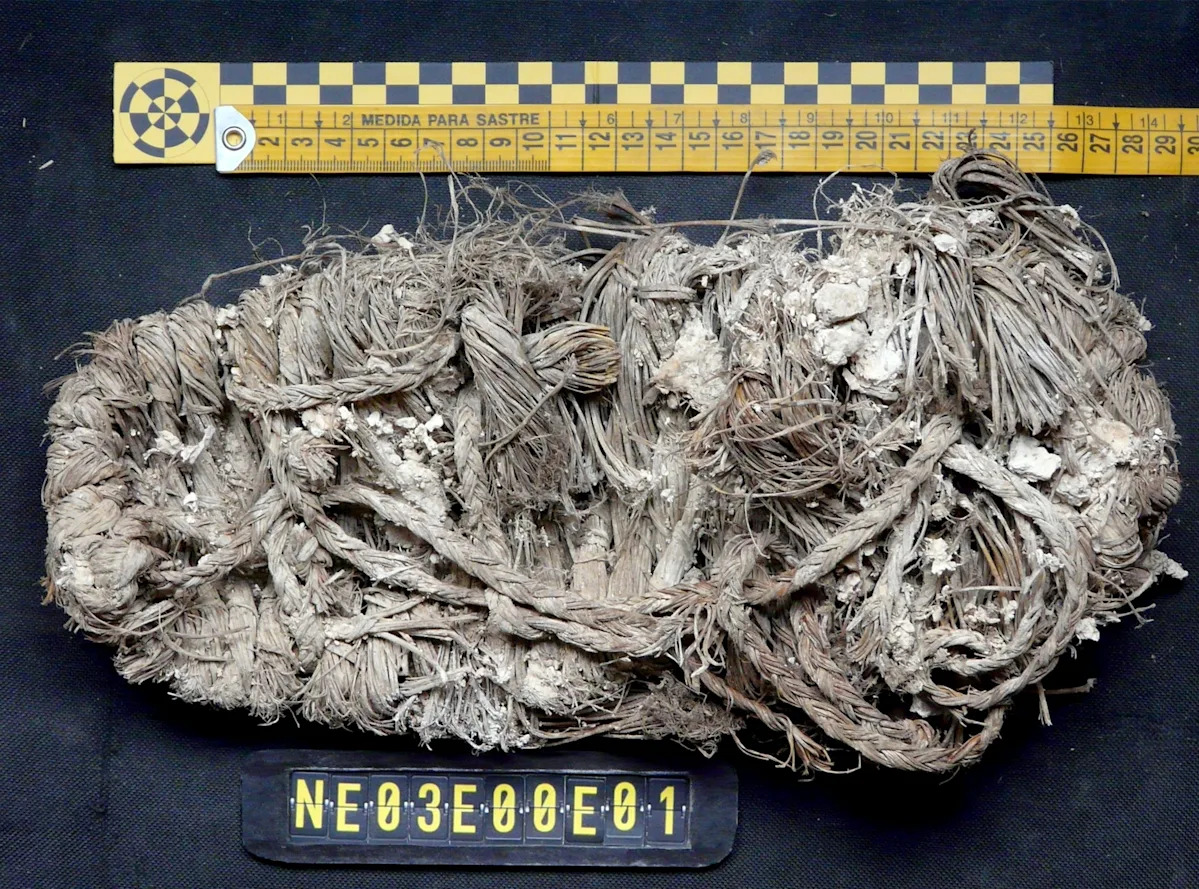

Undated agobía from the bearded vulture nests scientists found. Photograph By Sergio Couto

Undated agobía found in a bearded vulture nest. The woven shoes were frequently discarded and remade by their owners. Photograph By Sergio Couto

A unique kind of raptor, hoarding treasures

Bearded vultures are the only vulture species that specializes in eating bones, crunching into a carcass’s skeleton. Adding to the birds’ intimidating profile, they paint their feathers by bathing in red-orange mud. They live in the mountains, and often nest in protected nooks such as caves in cliffs.

A cave’s microclimate can protect the material that breeding vultures add to a nest each time they use it: tucking in new branches, lining the nest with sheep’s wool to keep eggs warm, delivering part of a goat’s carcass for their hungry chicks. “This material is very well-preserved during centuries,” says Antoni Margalida, an ecologist at the Pyrenean Institute of Ecology in Spain and lead author of the study. He likens the conditions inside the Spanish cliff caves to a natural history museum.

The nests may even remain after the birds themselves disappear. Bearded vultures vanished from southern Spain in the past century or so, as their overall European population shrank in the face of multiple challenges. Margalida and his colleagues dug into some of the old nests the birds left behind, analyzing the structures layer by layer like archaeological digs.

Inside 12 nests, scientists found a treasure trove of interesting objects. Many came from carcasses the vultures had scavenged—86 hooves, for example, and more than 2,100 bones. There were a few dozen eggshell fragments from hatched chicks.

The team also found human-made objects in the nests, including textiles and tools. A slingshot, for example, made from woven grass called esparto. They even found a crossbow bolt—which might have been used like a branch to construct the nest, or arrived lodged inside an animal carcass.

The researchers were able to use carbon-14 analysis to estimate the age of some items from two of the nests. The woven esparto sandal—one of several such shoes—was about 675 years old. A piece of basketry was younger, about 150 years old. Margalida was especially intrigued by a scrap of sheep leather, about six and a half centuries old, painted with lines of red ochre.

(The astonishing superpowers of nature’s most unloved animals)

Bearded vulture (Gypaetus barbatus) at feeding site and wildlife watching site, Pre-Pyrenees, Catalonia, Spain. Photograph By Staffan Widstrand, Nature Picture Library

Using the past to safeguard the future

The researchers still have a small mountain of items waiting for funding to be analyzed. Besides the archaeologically noteworthy objects, Margalida hopes to use other nest material to answer questions about the lifestyles of bearded vultures over centuries—and how best to keep them alive for generations to come.

For example, toxicological analysis of preserved eggshells could show when the birds were exposed to pesticides. The species of animal bones in the nests could tell researchers whether the birds’ diet changed over time; the species of tree branches could reveal shifts in the local plant population. Carbon dating could show just how long these resourceful birds may reuse the same nesting sites.

“We have several ideas to analyze in the future,” Margalida says. “I think that this material will offer a lot of possibilities.”

It’s common for many raptor species to reuse their nests, says Tricia Miller, a wildlife biologist and executive director of Conservation Science Global, Inc., who wasn’t involved in the new study. Birds may even use the same nests for centuries.

One golden eagle nest had so many layers of material added by generations of parents that it was 20 feet deep. In Greenland, carbon dating of guano showed that a gyrfalcon nest site had been occupied for more than two millennia.

“To think of mining that for ecological and archeological reasons is pretty cool,” Miller says.

Ancient bearded vulture nests in Spain contained many remnants of prey animals, including these goat horns. Photograph By Sergio Couto

Scientists don’t always know why human-made material ends up in vulture nests, but in some cases, there may be a practical reason. Margalida says he’s found a t-shirt in a present-day vulture nest, maybe a substitute warm lining when sheep’s wool wasn’t available.

The provenance of other objects is more mysterious. In Miller’s own surveys of osprey nests in New Jersey, she says, “We routinely pull all kinds of stuff out of those nests.” There are ropes, for example, and plastic items. Miller wonders whether the birds are attracted to unusual objects in the landscape, or might use them as a kind of decoration.

In an echo of the medieval shoe pulled from the vulture nest in Spain, Miller says, “I think the weirdest thing I found was a Croc.”