CBC Books asked Patty Krawec to curate a list of books to read for National Day for Truth and Reconciliation and Orange Shirt Day.

Krawec, of Anishinaabe and Ukrainian descent, is a member of the Lac Seul First Nation in Treaty 3 territory. She is a former social worker and the founding director of the Nii’kinaaganaa Foundation. Her work, centred on how Anishinaabe belonging and thought can shape faith and social justice, has been featured in Sojourners, Rampant Magazine and Midnight Sun, among others.

She is also the author of Becoming Kin: An Indigenous Call to Unforgetting the Past and Reimagining Our Future.

These books helped me understand the willfulness of that not knowing and peoples’ willingness to believe other stories about those schools.- Patty Krawec  (Goose Lane Editions)

(Goose Lane Editions)

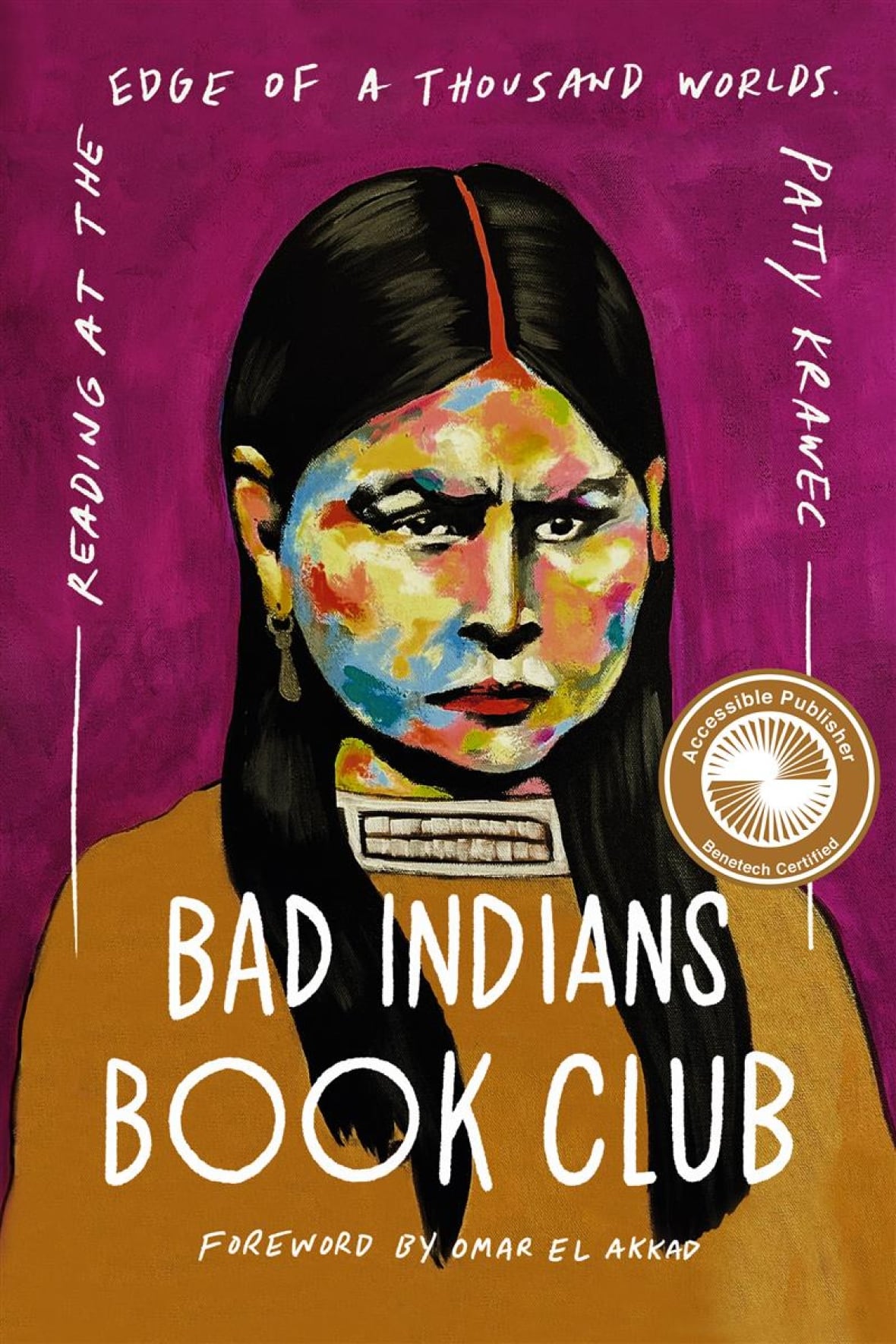

Her latest is Bad Indians Book Club, a nonfiction work which draws on conversations with writers and readers who she identifies as “Bad Indians” — those who reject the dominant European settler narrative.

Together, they reflect on how stories by and about marginalized voices can help us imagine new possibilities for identity and ways of being.

The titles that Krawec selected in this following list explore how acknowledging harmful histories help pave the way for a more hopeful future.

Why Patty Krawec curated this list

Anishinaabe storytellers say there was a time when the deer abandoned us. It was not a decision they took lightly, having made promises to care for us, but enough was enough and survival requires difficult decisions.

At first we didn’t notice, but week by week the hunters came back empty and as fall became winter anxieties started to rise.

September 30th is meant to be the beginning of that wrestling, not a single day to wear orange shirts, perhaps with a matching hula skirt and lei to dance with students as I saw outside an elementary school in the lower mainland of B.C. a few years ago.

It’s meant to be the beginning of a winter spent in examination and reflection, to challenge our assumptions about the stories we have been told about who we are and in this particular moment it is a critical exercise.

The preface to Monique Giroux’s Métis Music: Stories of Recognition and Resurgence (2024) offers a good example of this wrestling through her examination of her family history as well as the emptiness of land acknowledgements.

Eventually it was winter and we retreated to domed structures where layers of birchbark and hides held the warmth of a fire within. It was a long hungry winter and all we had were our stories.

We didn’t write things down back then, our stories were held in memory and dream. Reading was a collective activity with stories spoken aloud in the months with snow on the ground and over time these familiar stories took a different shape.

Certain details became more important, and over time the realization dawned that it was we, not the deer, who had caused this. By the time spring arrived, we had examined our actions through the stories we told about our history and the world around us and we wanted to make things right. Reconcile, if you will, having spent the winter wrestling with truth.

[September 30th] is meant to be the beginning of a winter spent in examination and reflection, to challenge our assumptions about the stories we have been told about who we are and in this particular moment it is a critical exercise.- Patty Krawec

There are many books written specifically about residential schools: memoirs and history; political analysis and the Report from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission itself; podcasts, poetry, song and art.

This collection of books I recommend to you takes a look at the schools as well as the history of Canada and whiteness itself which is what allowed the schools to exist in the first place and have the afterlife that they do.

LISTEN | Patty Krawec on The Next Chapter:

The Next Chapter25:32What does it mean to be a Bad Indian?

A history of colonialism

We begin with The History of White People by Nell Irvin Painter (2010). It is a fascinating study of the history of whiteness from Enlightenment era-race theory and down a crooked road towards the crooked house we currently find ourselves in.

As a former social worker, I found the chapter on the emergence of the social work profession fascinating and discomfiting much the same way that In Search of April Raintree by Beatrice Mosionier (2011) was, a novel that brings together residential schools and child welfare.

(University of Regina Press)

(University of Regina Press)

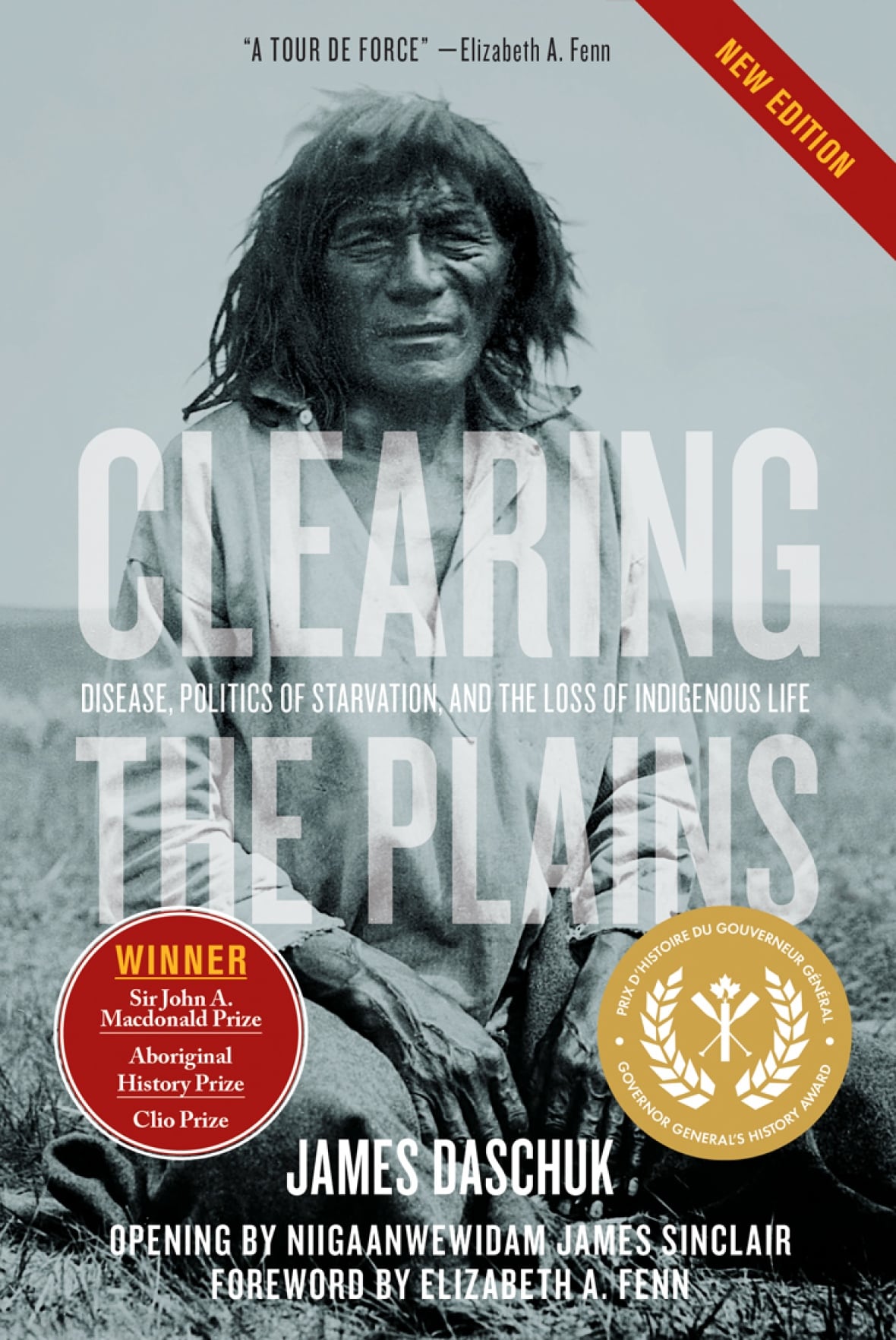

Then we turn to Clearing the Plains: Disease, Politics of Starvation, and the Loss of Aboriginal Life by James Daschuk (2013). This is a gut-wrenching book about Canada’s own policies of starvation to force compliance, clear land and make room for European settlement of the Prairies.

These policies persisted through residential schools where inadequate medical care and nutritional experiments compromised the health of generations of children while developing things like Canada’s Food Guide.

Talking about the settlement of the Prairies,The Constructed Mennonite: History, Memory, and the Second World War by Hans Werner (2013) and Mennonite and Nazi: Attitudes Among Mennonite Colonists in Latin America 1933-1945 by John D. Thiesen (1999) offer us a look at one particular group of settlers.

My maternal grandmother was Mennonite, one of those who lived in the Chortiza colony in Ukraine, fleeing Stalin and finding safety in Hitler’s Germany before coming to Canada as a refugee in 1951, the same year my paternal uncles were playing for the Sioux Lookout Blackhawks. These books examine how communities with a deep commitment to faith and pacifism embraced the ethnic pride of German National Socialism and justified, or ignored, the atrocities of the Third Reich.

I have long struggled with Canadian’s insistence that they didn’t know about residential schools, a claim that seemed incredulous given the number of people who lived nearby and worked in these schools. These books helped me understand the willfulness of that not knowing and peoples’ willingness to believe other stories about those schools.

Looking back, moving forward

A similar examination runs through Omar El Akkad’s book One Day, Everyone Will Have Always Been Against This (2025). This is a book about Palestine, but it is also about coming to terms with the stories he has been told about these western nations in which his family found safety, reckoning with the similarities between here and there.

In his first book, American War (2017), he imagined an inversion of history where the realities of the nations he grew up in took place here in the west. This book remembers that they did take place here.

(University of Manitoba Press)

(University of Manitoba Press)

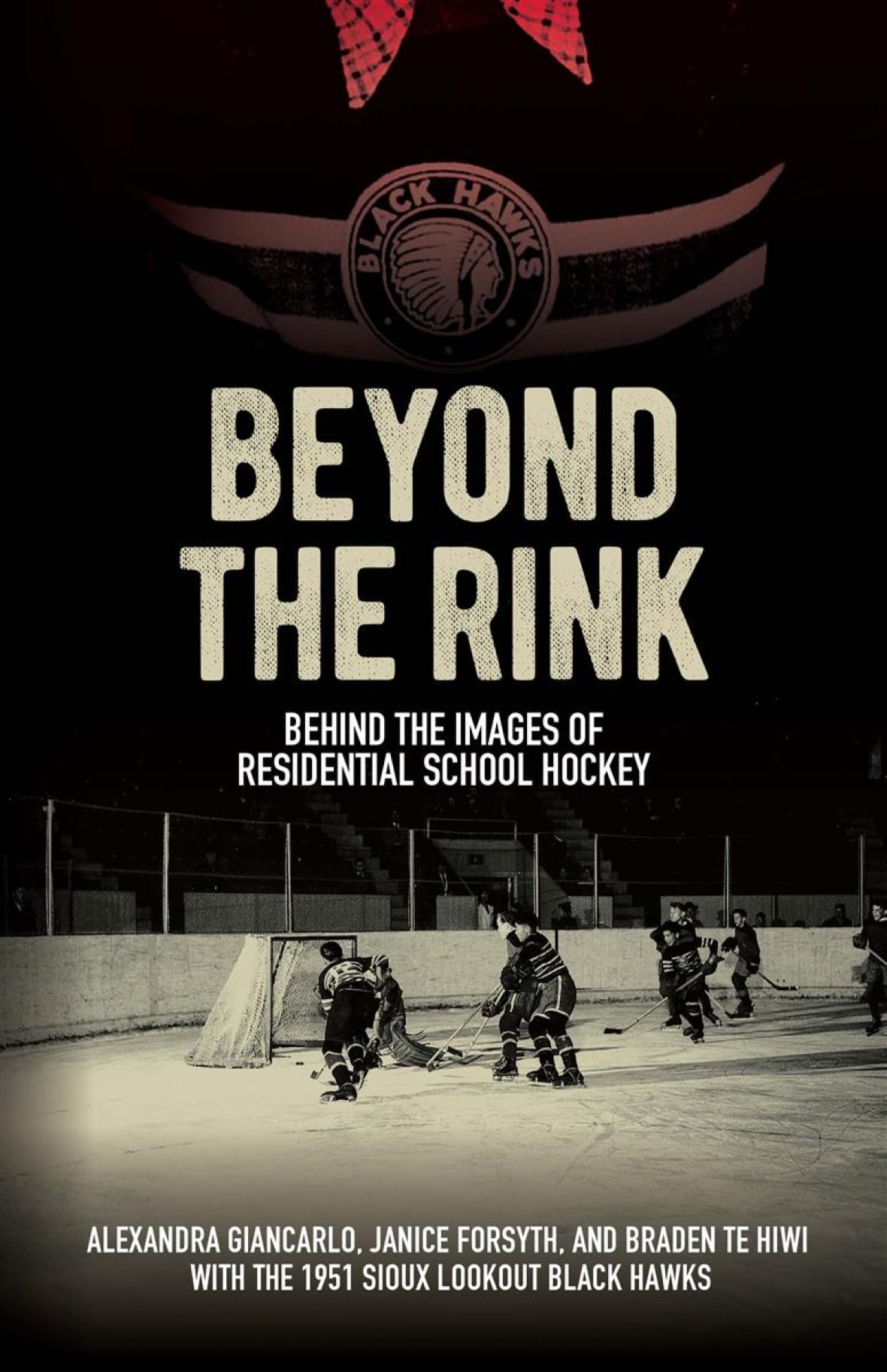

That willingness to believe other stories told about residential schools is examined in Beyond the Rink: Behind the Images of Residential School Hockey by Alexandra Giancarlo, Janice Forsythe and Braden Te Hiwi with the 1951 Sioux Lookout Blackhawks (2025) which tells the story behind photographs taken in 1951 by National Film Board photojournalist Gar Lunney.

In the early years of the Cold War, the NFB of the 1950s wanted to tell stories of Canadian identity, uplifting and celebratory stories that showed an idealized version of Canadians. That vision included the Sioux Lookout Blackhawks, and the story these photos told was one of Indian boys playing the most Canadian of sports and becoming Canadian. This is not, of course, the story that Kelly Bull, Chris Comarty and David Wesley shared with the authors.

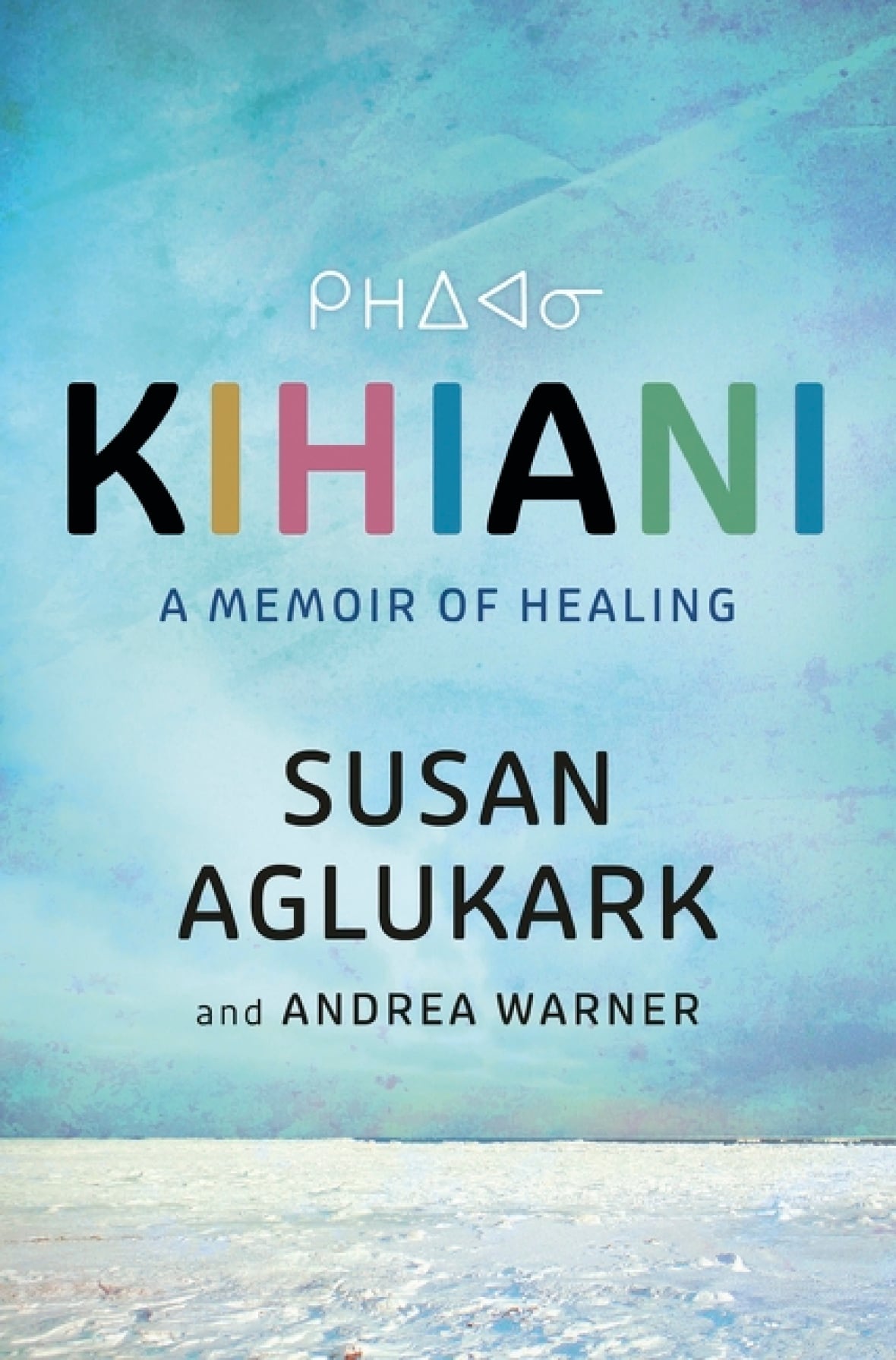

I first heard about residential schools through the songs of Susan Aglukark, an Inuk singer/songwriter whose memoir Kihiani: A Memoir of Healing (2025) includes reflections on the trauma of residential schools in her own life and her community. Jesse Wente’s memoir Unreconciled: Family, Truth, and Indigenous Resistance (2021) includes the plaintive recognition that he is the kind of Indian residential schools intended to create along with a powerful refusal to be that Indian.

Michelle Good’s novel Five Little Indians (2020) tells a story of residential school and survival afterwards just as Lynne Sherry McLean’s novel Where Mary Went (2010) does. Based on stories told to her by her grandmother, this novel is set in the Mush Hole, a residential school not two hours from where I grew up that closed when I was five years old.

Children’s books like David A. Robertson’s When We Were Alone (2024) and Shi-shi-etko by Nicola I. Campbell (2005) help parents broach the topic with children, and No Time to Say Goodbye: Children’s Stories of Kuper Island Residential School (2001) is a children’s book by Sylvia Olsen featuring the residential school featured in Duncan McCue’s 2024 true-crime podcast Kuper Island. There are so many books.

(HarperCollins )Our stories to tell

(HarperCollins )Our stories to tell

To return to our story, I don’t know what the deer were doing that winter. That isn’t our story to tell, but I imagine that they were finding comfort in their own stories and memories as they recalibrated to a life where they were no longer under constant threat.

I too find comfort in Anishinaabe stories and memories such as the works of Leanne Betasamosake Simpson who relies on our traditional stories to write books about resurgence and governance like As We Have Always Done (2017) and her most recent A Theory of Water (2025).

Simpson joined with Robyn Maynard to write Rehearsals for Living (2022) which perhaps reflects something else the deer were doing during their respite: building trans-national relationships with others who had experienced the harms of nation-building.

When the Anishinaabe eventually did meet with the deer, they did not move immediately from truth to reconciliation. In between these things is a necessary reckoning and they had to listen for as long as the deer, strengthened by those months of resting in their own stories, wanted to speak.

The apology they made emerged from that reckoning, which they were able to have because of their own months of examination and reflection.

September 30th is meant to begin a season of reflection and re-assessment, not a once and done but a constant renewal as we learn new things about who we were, are, and might yet be.

There are enough books here, and in the bibliographies at the end of each of them, to get you through to the spring.

And like the deer in this story, when you’ve wrestled with the truth and are ready to reconcile, we’ll be here.

Baamaapii

Patty Krawec’s must-read books: