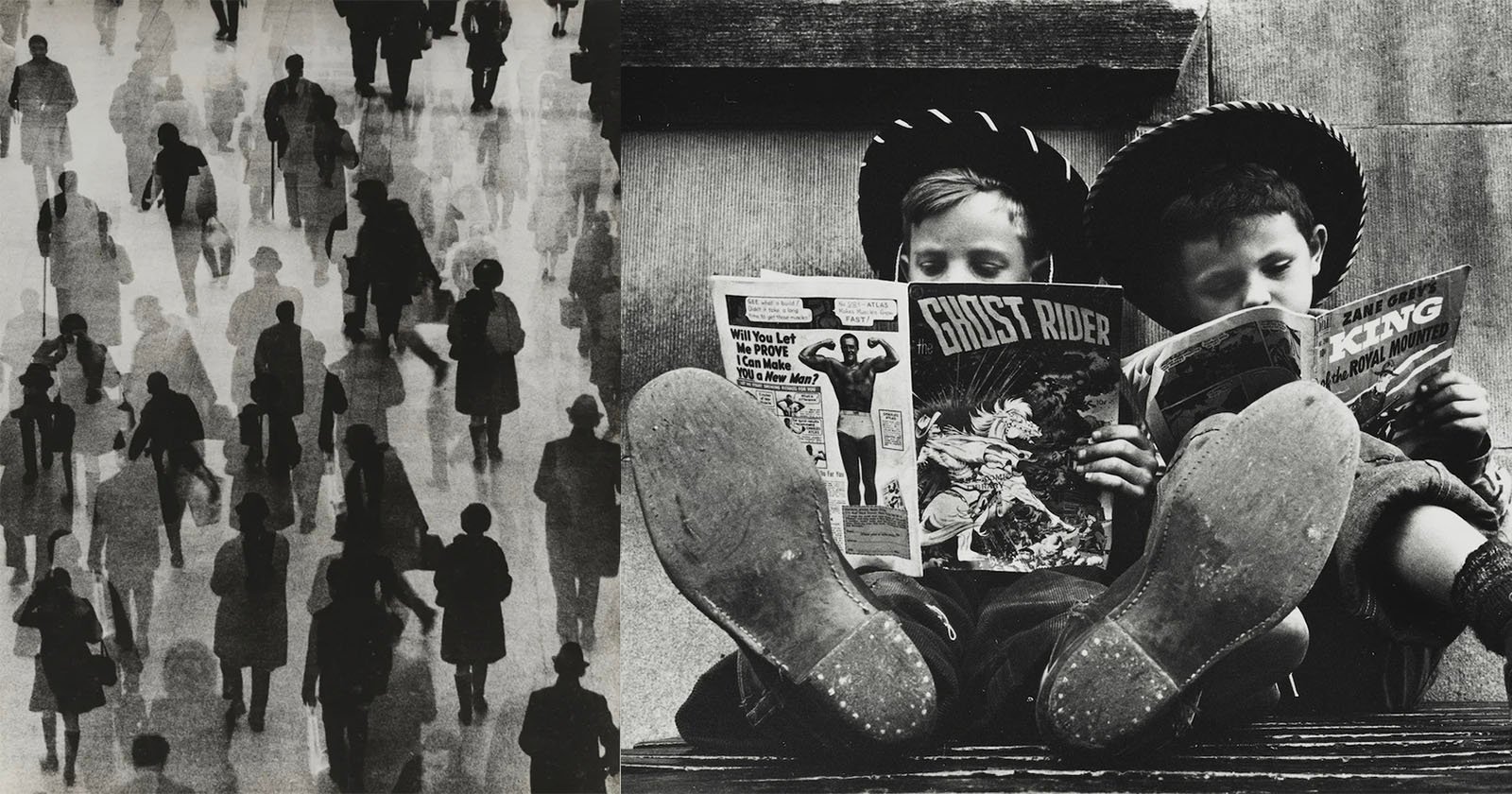

Benn Mitchell, Two Cowboys Reading Comic Books, 1951. | © Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents

Benn Mitchell, Two Cowboys Reading Comic Books, 1951. | © Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents

The Center for Creative Photography at the University of Arizona has received the archive of renowned Life magazine photographer Benn Mitchell, as well as a $1 million gift.

Esther Mitchell donated the entirety of her late husband’s archive to help preserve the work of the photographer who captured “American vitality” across the mid-20th century. The $1 million will be used to establish the Benn and Esther Mitchell Endowed Collection Fund.

Benn Mitchell, Crowds, 1975. | © Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents

Benn Mitchell, Crowds, 1975. | © Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents

Esther says she had been searching for the right home for Benn’s work and learned about the Center for Creative Photography’s reputation for preserving archives. “They don’t just store photographs. They study them, teach with them and share them with the public. That combination really made me feel it was the right place,” Esther says.

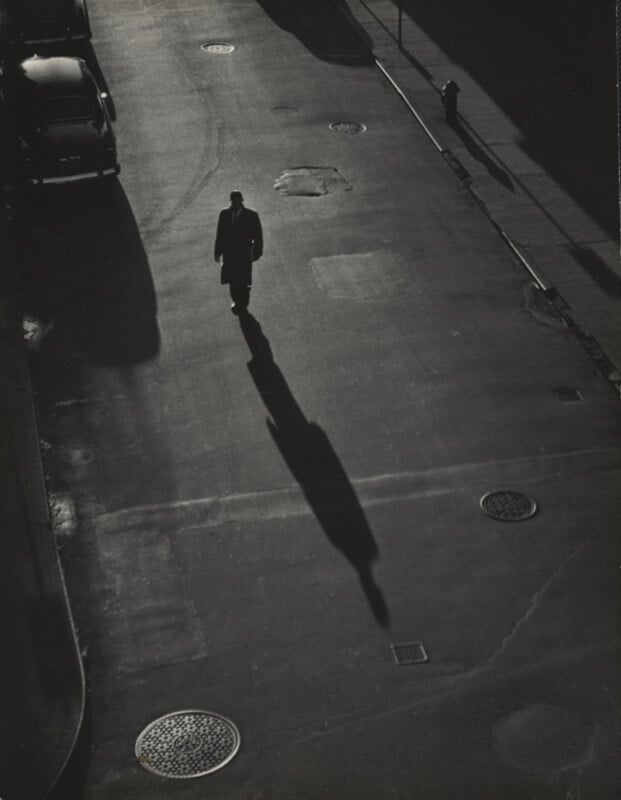

Benn Mitchell, Shadow of Man in Street, 1952. | © Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents

Benn Mitchell, Shadow of Man in Street, 1952. | © Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents

Included in Benn Mitchell’s archive are his negatives and prints, plus clippings and publications featuring his work, and also some of his gear. Through the donation, the Center for Creative Photography now holds the copyright to Mitchell’s work, which will be made available for education, exhibition, and scholarly study.

“The Center for Creative Photography [CCP] is the ideal home for Benn Mitchell’s archive, and we are extremely grateful to Esther Mitchell for choosing the CCP to be the steward of Benn’s legacy,” says the director of the CCP, Todd Tubutis. “Esther understands the critical importance of collections care, and her endowment gift will help ensure we are able to maintain best practices in preserving our collection and making it accessible to everyone.”

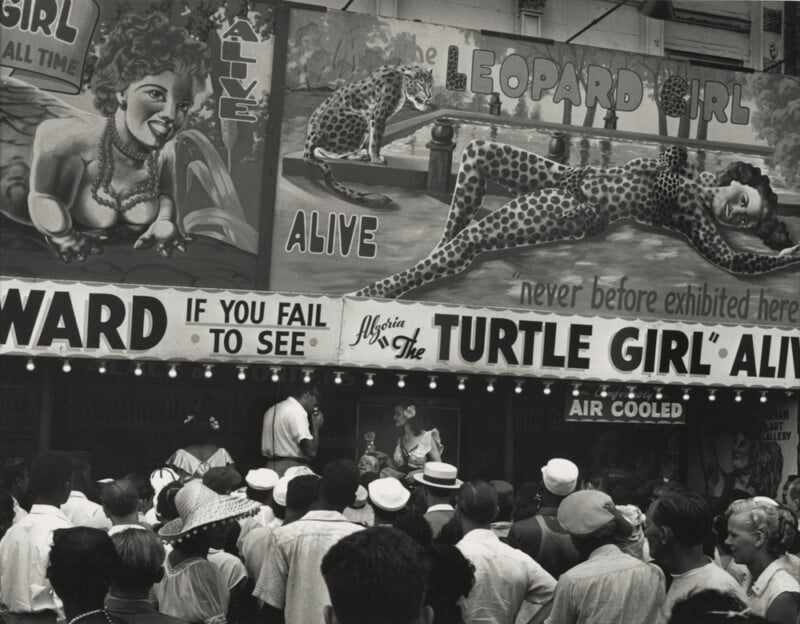

Benn Mitchell, Billboard Sideshow for Leopard Girl with Crowds Below, 1950. | © Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents Who Was Benn Mitchell?

Benn Mitchell, Billboard Sideshow for Leopard Girl with Crowds Below, 1950. | © Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents Who Was Benn Mitchell?

Benn Mitchell, born in New York in 1926, received his first camera at the age of 13 and sold his first picture to Life when he was 16. The photo was a classic weather shot showing his little brother trying to keep cool during a heatwave by sitting on a block of ice while eating ice cream. Life paid him $25.

“He thought he was a rich, successful photographer right then. From that point on, he was always looking for the next picture,” his widow Esther says.

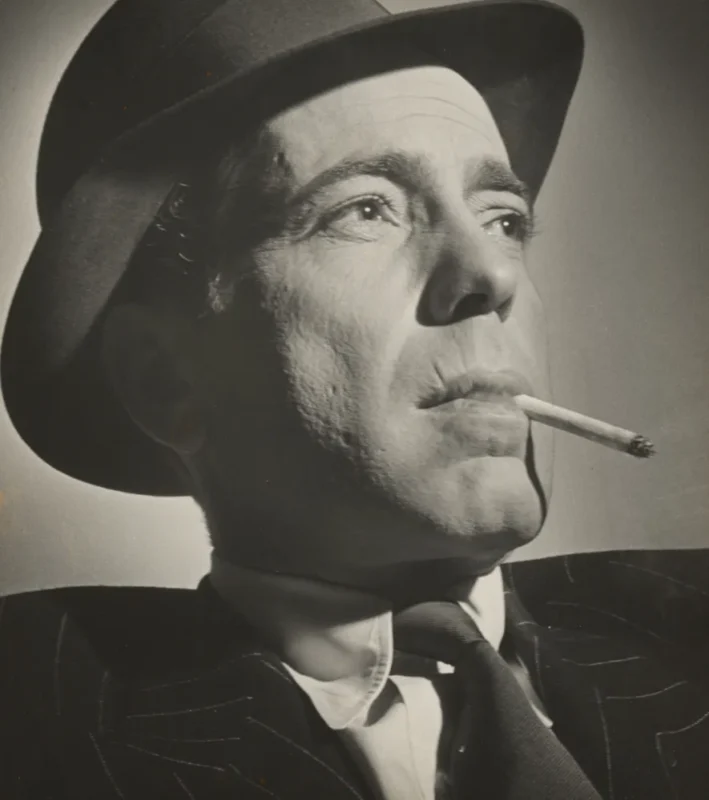

Benn Mitchell, Humphrey Bogart, 1943. | © Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents

Benn Mitchell, Humphrey Bogart, 1943. | © Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents

At 17, Mitchell moved to Hollywood and photographed the likes of Humphrey Bogart before spending two years as a photographer in the U.S. Navy. In 1951, he returned to New York and opened a commercial studio with Esther. There, he undertook all types of photography, including stunning Manhattan street scenes and documenting American Indian culture. He also undertook commercial assignments in advertising and stock photography.

“Benn had the patience to wait for the right day, the right light and the right moment for the perfect picture,” Esther says. “He could spend hours — sometimes all night — in the darkroom making sure the print matched the image he envisioned.”