Settings

In 2010, the Government of Ethiopia restructured its health system into three tiers—primary, secondary, and tertiary care—to effectively deliver health services across the continuum. Emphasizing the primary health system, a typical woreda (i.e., district) ideally comprises one primary hospital, 4–5 health centers, and 20–25 health posts, serving a population of approximately 100,000 people. Primary health care services encompass promotive, preventive, curative, and rehabilitative care delivered through static facilities (health posts, health centers, and primary hospitals), at home or in the community, and through outreach services. These services are implemented via the Health Extension Program (HEP) and involve the engagement of community volunteers.

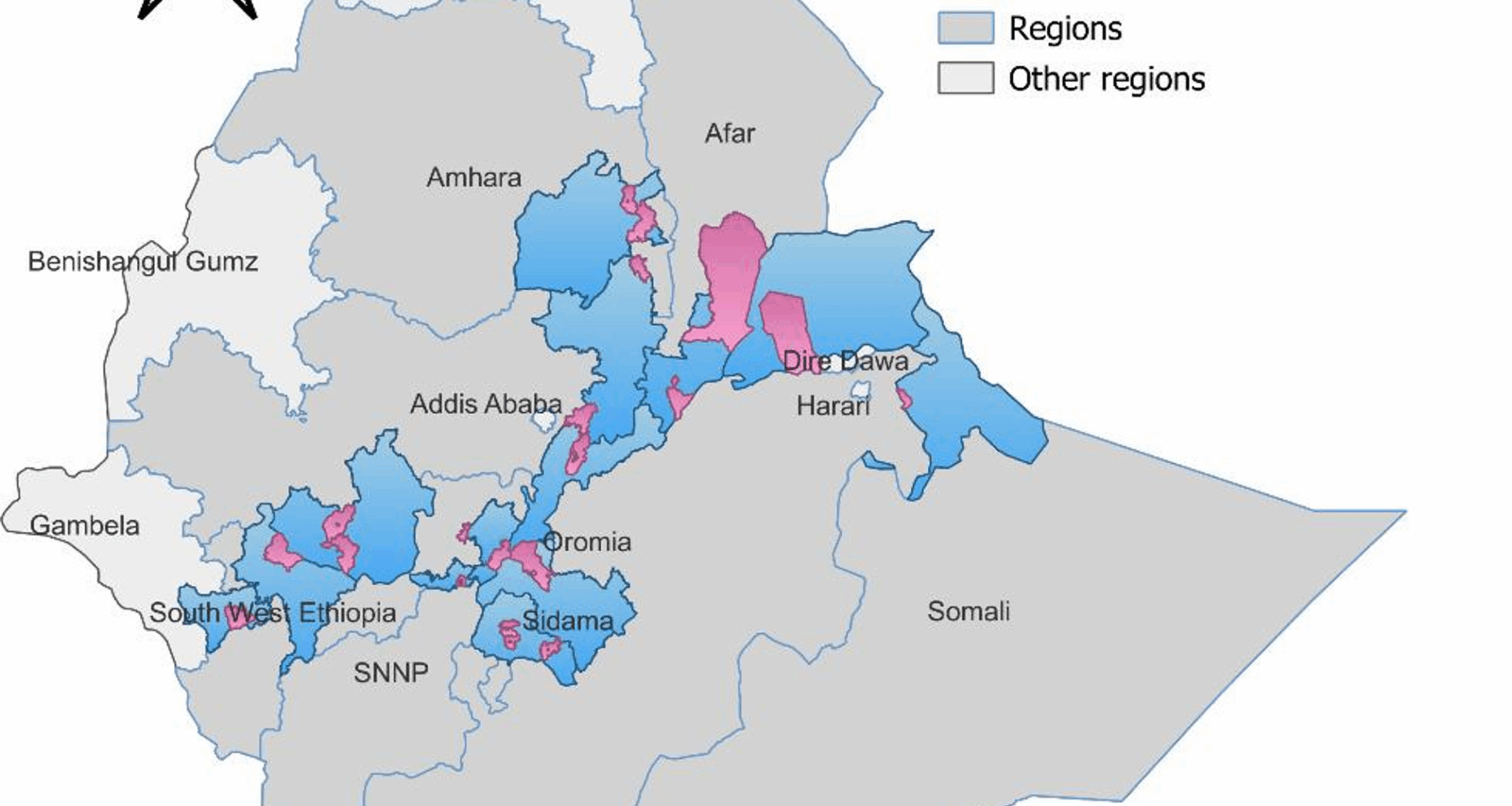

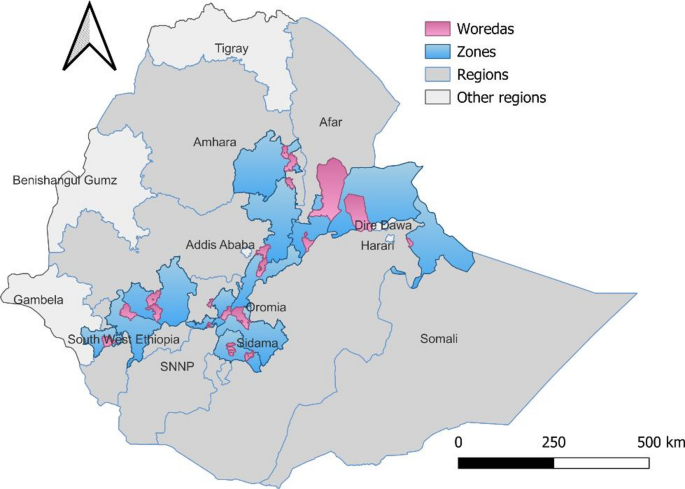

The study area includes all 20 targeted woredas—16 agrarian and 4 pastoral—across seven regions of Ethiopia: Afar, Amhara, Oromia, Sidama, Central, Somali, and Southwest Ethiopia. Pastoral communities in Afar and Somali regions are known for their sparse populations and mobility, as they traverse large areas in search of pasture and water for their herds. Additionally, many parts of these regions are hard to reach due to poor infrastructure. While the agrarian woredas have better infrastructure and access to health services (Fig. 1).

SSD project intervention woredas

Design

This study utilized data from formative implementation science research to monitor the Project outcomes. A stratified multistage sampling technique, stratified by agrarian and pastoral regions, was employed to recruit women with infants aged 0–11 months. The survey gathered maternal and newborn health (MNH) care information from women who had given birth in the 12 months before the survey.

Sampling strategy

A two-stage stratified cluster sampling technique was used for household selection. The list of kebeles and their corresponding catchment populations was obtained from the intervention woredas. In the first stage, 94 kebeles were randomly selected as primary sampling units—61 in agrarian and 33 in pastoral regions. Sample sizes within each kebele were proportionally allocated based on the population size of each kebele.

An updated list of households with women having infants ages 0–11 months, along with their unique household identifiers, was retrieved from the family folders at the respective kebele health posts. This list served as the sampling frame for data collectors. In the second stage, a systematic random sample of households was drawn from this frame, proportional to the kebele clusters.

Sample size

The required sample size to monitor the program’s effectiveness was calculated using StatCalc, based on a comparative cross-sectional household study design. A double population proportion formula was employed to assess the large-scale implementation of the SSD investment on household maternal and child health care behaviors and practices. The calculation assumed a 95% confidence level (Zα/2 = 1.96), a 5% margin of error, a design effect of 1.5, 80% power, and a two-sided alpha error of 0.05. We aimed to detect a 15-percentage point increase in the uptake of skilled delivery and basic vaccinations by the Project’s end, with stratification between pastoral and agrarian settings. Accordingly, a sample of 1,922 mothers of children ages 0–11 months was recruited, with 1,118 from agrarian and 804 from pastoral regions.

A stratified random sample of 62 health centers—53 in agrarian areas and 9 in pastoral areas—was selected by program domain and region type. Additionally, all 5 primary hospitals in agrarian woredas (none in pastoral woredas) were included in the survey to assess their readiness to provide quality RMNCH services and their practice of integrated service provision.

Data collection

The questionnaires for the regions of Afar, Amhara, Central Ethiopia, Sidama, and Southwest Ethiopia were administered in Amharic; those for the Somali region were in Af-Somali; and the Oromia region’s questionnaires were in Afaan Oromo.

We deployed 53 data collectors and supervisors, conducting six days of training followed by a one-day field test in Addis Ababa from July 1–6, 2024. The questionnaires were administered to mothers in their homes. The interviews gathered data on sociodemographic and obstetric characteristics, gender-related measures, care-seeking behaviors across the continuum of maternal and newborn health, essential newborn care, family planning, and immunization services (Additional file 1). Facility audits were conducted using informant interviews and observations (Additional file 2).

Data collection was facilitated using a web-based mHealth platform (SurveyCTO) via tablets and smartphones, which also enabled the collection of GPS data. During the data collection phase, field supervisors provided continuous oversight. Survey supervisors and coordinators monitored and supervised the fieldwork to ensure data quality, which included randomly revisiting selected households to validate responses. The project’s Monitoring and Evaluation team implemented a central data quality assurance procedure, involving daily preliminary analysis of data submitted to the central server, prompt resolution of field-reported issues, and real-time communication of necessary adjustments to the entire data collection team.

Measurements

The outcome variables for this study were the uptake of postpartum family planning (PPFP) among mothers with children ages 0–11 months and initiation of child vaccination during the first year of life. The independent health-system-related variables of interest included receipt of PPFP counseling during antenatal care (ANC), childbirth and/or the postpartum period, receipt of immunization counseling during childbirth and/or postpartum care, and missed opportunities for birth vaccinations. Additional covariates included individual sociodemographic factors such as religion, maternal age, education, household wealth index, parity, and distance to the nearest health facility. Obstetric and gender-related factors such as women’s empowerment, ANC contacts, delivery location (facility or home), and postnatal care were also considered. Administrative region and area of residence (clusters/kebeles) were considered as community-level random components.

Integration of services in this study refers to the coordinated delivery of multiple maternal and child health services—such as family planning counseling and provision, maternal and newborn care, nutrition, and immunization—within the same service point and visit, across RMNCH touchpoints.

Recipient of vaccination was defined as an infant aged 0–11 months who had received at least one age-appropriate vaccine, as verified by parental report or vaccination card. Missed opportunities for vaccination after facility birth were defined as infants who did not receive either the birth dose of polio (Polio 0) or the BCG vaccine before leaving the facility or being discharged after delivery. Women’s empowerment was measured based on their reports of decision-making—either alone or jointly with their husbands—regarding seeking ANC, choosing the place of delivery, using contraception after delivery, seeking care for themselves, and seeking care for their baby. If women reported having a say in all five decision-making areas, they were classified as “empowered to decide”. If they did not report having decision-making power in all five areas, they were classified as “not empowered to make decisions alone or jointly”. A wealth index score was constructed for each household using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) based on the household’s possessions (such as bank account, electricity, watch, radio, television, mobile phone, telephone, refrigerator, bed, electric stove, bicycle, motorcycle, and three-wheeler bajaj), assets (including number of goats, milk cows or bulls, sheep, horses, donkeys, mules, camels, and chickens), and characteristics (such as type of latrine, water source, floor, and wall material). Households were then ranked according to their wealth scores and divided into three wealth categories: poor, middle, and rich.

Analysis

Data were analyzed using Stata version 15.1. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the respondents’ characteristics. Differences between respondent characteristics were examined using Pearson’s chi-square test, adjusted for the cluster survey design. Post-stratification sampling weights were applied to account for non-proportional sample allocation across regions, ensuring the representativeness of survey estimates through weighted analysis.

Facility- and household-level data were analyzed separately, as the relatively small number of facilities and the sampling design did not allow for reliable linkage between individual women and the facilities where they sought care.

Random-intercept logistic regression models were fitted to estimate associations between individual- and community-level variables and the likelihood of adopting PPFP and child vaccination within the first year of life. These models allowed the probability of adopting PPFP and child vaccination to vary randomly across communities, assuming fixed effects for individual-level characteristics across all communities. The analysis utilized the Stata commands `xtlogit` and `xtmelogit`. The null model was fitted without explanatory variables.

The program’s theory of change was used as a framework to guide our analytic approach, informing the inclusion or exclusion of specific variables across models. In addition, iterative methods based on backward elimination and forward selection were used to select explanatory variables. For this purpose, independent variables were retained in each model if their p-value was less than 0.2 in the analysis. Model goodness-of-fit was evaluated using global Wald statistics, likelihood ratio tests for cluster-level random effects, and sensitivity of the quadrature approximation. The Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) were used to assess model suitability and fit.