Researchers studied the famous “waggle dance” of honeybees, which they use to communicate to one another about the location of resources, to evaluate whether they integrate memory of the terrain into their flight. They do.

A poetic form of communication, though it may be, the waggle dance is thought to convey only a vector—direction and distance from the hive to a food source. A recent study published in Current Biology investigated the remarkable communication strategy to a new degree of depth.

Did the dance teach the bees, if you can imagine a bee moving with fear, though emotion didn’t play into this study, to anticipate a bump in the road at a specific point on the journey? Are the bees, in fact, pantomiming the way itself?

Researchers trained a small group of foragers to visit a feeder located north of a hive along a gravel road. However, they released the bees from three different sites, discovering that the dance was even more complex and detailed than they had originally understood.

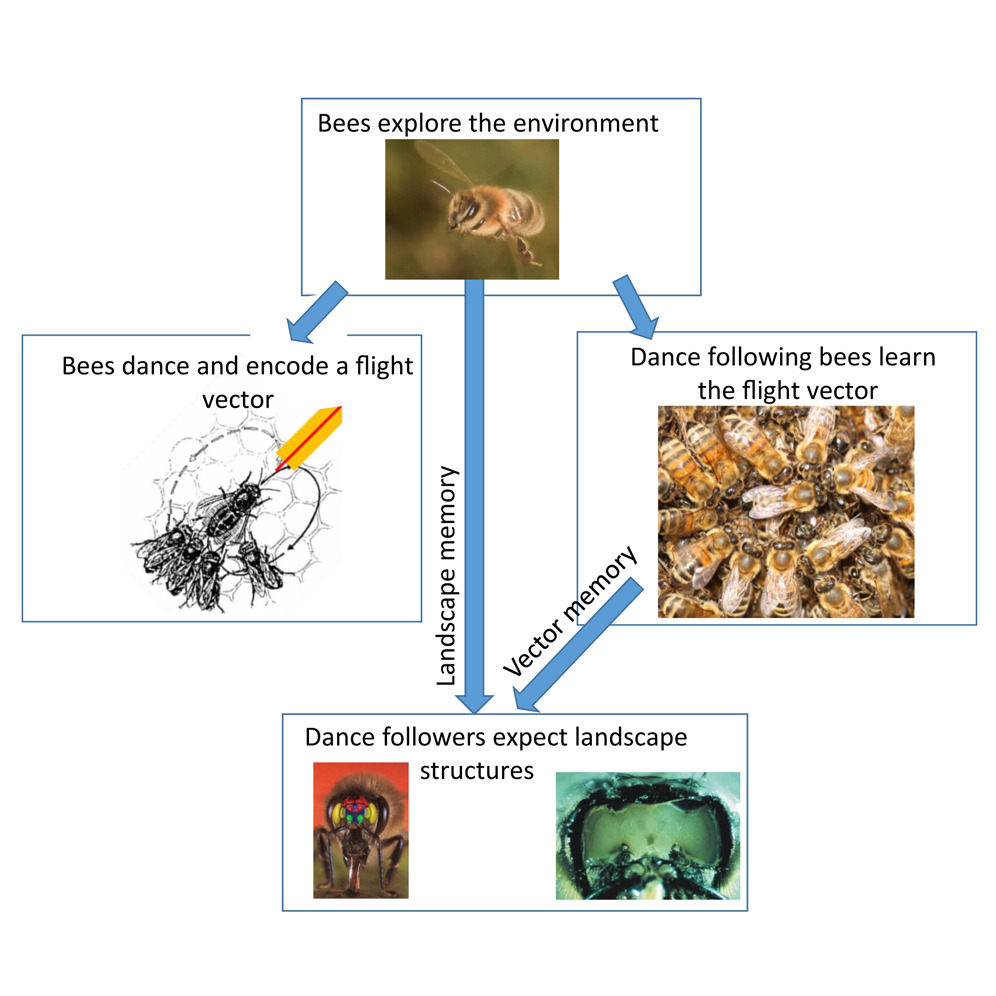

A diagram of the dance that includes spatial expectations, Wang et al.

A diagram of the dance that includes spatial expectations, Wang et al.

A truly intelligent and efficient form of communication

Researchers placed a feeder with a sugar solution north of the hive along a gravel road and trained forager bees to visit it. One site, as reported by Phys, had a distinct path, whereas another lacked these types of markers.

Then they let the bees perform their magic trick of dancing to attract mates and indicate where the food was located. They had never visited the hive themselves. Researchers awaited to determine whether any information about the landscape, what to anticipate on the flight itself, was communicated in “the waggle.”

“We employed harmonic radar tracking, a powerful tool for recording the detailed flight trajectories of individual bees,” the study authors wrote.

Researchers found that the receivers of the dance weren’t just following the direction and distance indicated by the waggle dance. They integrated the dance’s vector information with the memory of landscape features that they might encounter along the way.

“In the absence of an expected landmark, their search behavior became more exploratory,” according to Phys. “They flew farther and in less straight paths,” according to a news release by the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

A multifaceted form of communication

“In conclusion,” study authors stated in the study, “our experiments addressed the question of whether the vector information conveyed by the dance is integrated into a recruit’s spatial representation—constructed from its own experience—and whether this integration occurs within a common frame of spatial reference shared by both the reported symbolically communicated vector and self-experienced locations.

The recruits developed an expectation, they continued, about the landscape that they would fly over when bees integrated the dance, as if “body language” communicated so much more than words did. Researchers called it “a multifaceted form of communication.”

What they saw was that the cognitive structure at play here is “most adequately conceptualized as a cognitive map.”

So bees are even more impressive than we already give them credit for. These intelligent bees aren’t just following the vector; they retain a spatial layout of the environment and incorporate it into their navigation.

“Our study reveals a higher level of cognitive complexity in honeybee communication. Waggle dance-following bees do not simply follow a blind vector instruction; they integrate it with a cognitive map of their surroundings built during earlier exploratory flights. This allows them to form expectations and navigate more efficiently,” said the lead researcher in Phys.