Five years after schools, businesses and employment centers throughout Maryland were shut down by COVID, the state’s persistent digital divide continues to follow long-standing racial and economic lines.

The pandemic drew greater attention to the problem of digital inequity, as the shift to online work and school highlighted why connectivity and digital skills were essential. But disparities remain in areas both rural and urban.

This landscape largely mirrors national trends, according to John Horrigan, a senior fellow at the Benton Institute for Broadband and Society.

With the Appalachian Mountains to the west, rural expanses along the Eastern Shore and economically disadvantaged neighborhoods in Baltimore City, Maryland illustrates the complex challenges of expanding broadband infrastructure, he said.

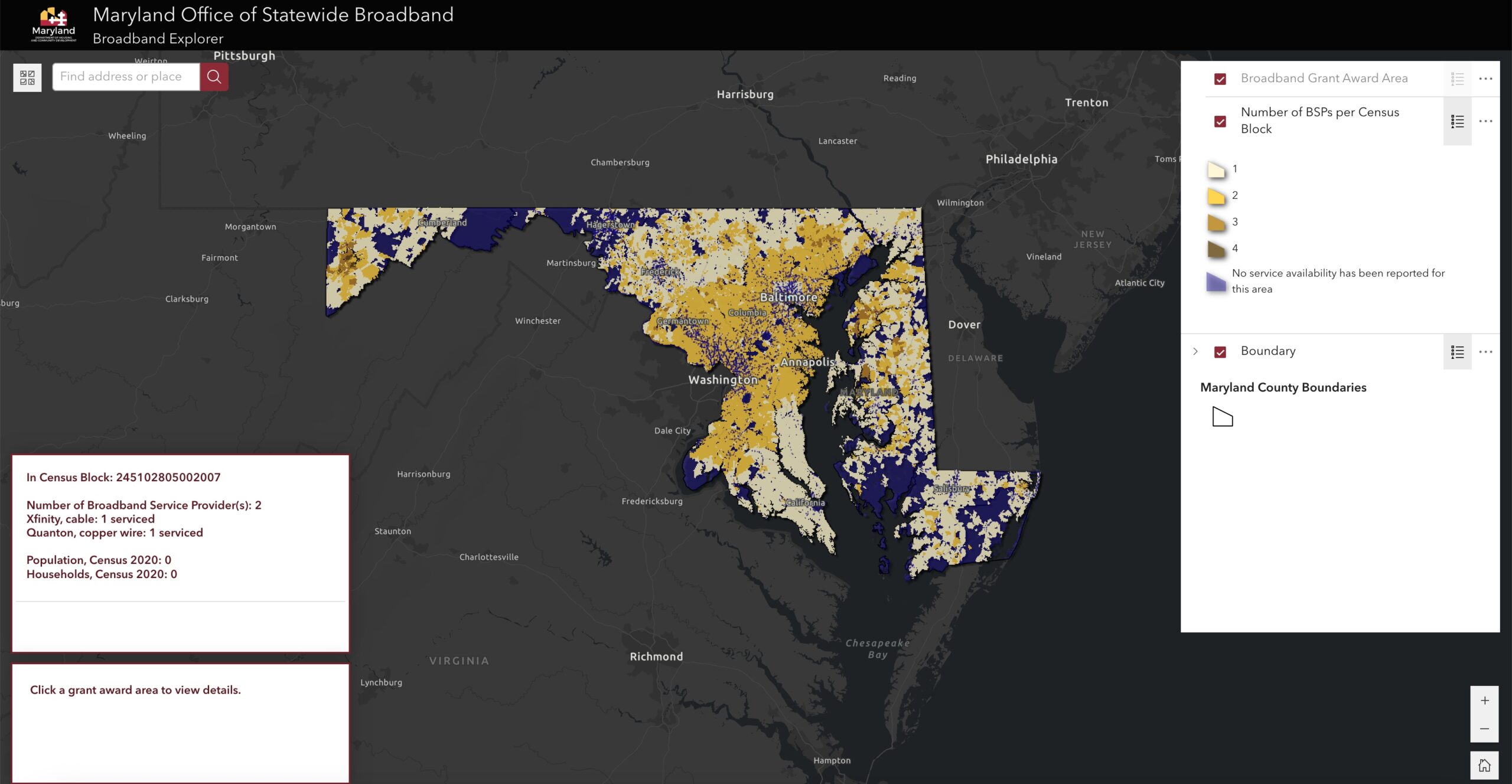

The Office of Statewide Broadband has a tool that tracks broadband availability across Maryland

The Office of Statewide Broadband has a tool that tracks broadband availability across Maryland

Overall, 80% of Maryland households have some form of broadband access, including cable, fiber-optic, or digital subscriber line (DSL) connections, according to the 2024 American Community Survey (ACS), an annual demographics study conducted by the US Census Bureau.

11% of Maryland households depend exclusively on cellular data plans, without access to a broadband connection.

18% of Maryland households earning less than $20,000 a year don’t have an internet subscription.

10% of households earning between $20,000 and $75,000 a year don’t have an internet subscription.

7% of households rely on a smartphone as their only computing device.

The 2024 data highlights digital redlining, which refers to the unequal investment in broadband infrastructure that disproportionately impacts people of color, low-income communities and rural areas. For instance, Black Marylanders account for about 29% of the state’s population but represent 38% of households with a computer and no internet subscription.

ACS data also shows progress, particularly in Baltimore City, in expanding internet access. In 2019, 20% of city households had no internet connection; today, that figure has dropped to 12%. Still, the households without access remain concentrated in predominantly Black neighborhoods in West Baltimore, per a Baltimore Neighborhood Indicators Alliance map.

Expanding internet access remains a challenge in rural areas as well. In Somerset County — located along Maryland’s Eastern Shore and home to one of the state’s highest poverty rates — 2023 ACS data suggests that broadband adoption lags behind the statewide average:

16% of households have no internet at home

11% of households have at least one smartphone and no other computing device

19% have a cellular data plan but no other internet subscription

57% have broadband of any type, such as cable, fiber optic or DSL

Horrigan emphasized that reducing internet subscription costs will be key moving forward. He recently examined how the end of the Affordable Connectivity Program, which offered a $30 monthly service subsidy for eligible households, has affected low-income families’ ability to stay online.

He added that while programs like the Broadband Equity, Access and Deployment (BEAD) Program are important for expanding infrastructure, people won’t join new networks if they remain unaffordable.

Originally, states that didn’t use their full BEAD allotment for network construction could allocate the remaining budget as “nondeployment funds” to support network adoption through initiatives like digital skills training and workforce development. Now, the status of these funds is uncertain, with Maryland lawmakers seeking clarification on how they can be used.

Horrigan worries these nondeployment funds might be clawed back by the federal Department of the Treasury.

“It’s a mistake. It’s deciding against all evidence that the entirety of the digital divide is about the network, when that is part of it for sure.” Horrigan said. “But these other elements — digital skills and affordability of service — are the other key part of it.”

Maria Eberhart is a 2025-2026 corps member for Report for America, an initiative of The Groundtruth Project that pairs emerging journalists with local newsrooms. This position is supported in part by the Robert W. Deutsch Foundation and the Abell Foundation. Learn more about supporting our free and independent journalism.