There is the well-meaning PT teacher (a wonderful Aruvi Madhan), who fights with his ‘own’ and even Pasupathy, to give Kittan the best possible platform. There is a Tamil captain of the national team, a good-natured selector, and his daughter, who manages to be Kittan’s step ladder to great things. There is Kandhasami, who sees talent over caste, to give him a bigger platform. There is Pandiyaraja, who shuts down voices that call Kittan out for his seeming treachery, and points out that true talent has to be nurtured. Even the big bad system is shown to have traces of warmth. While there is a case to be made about the whitewashing of people who see ‘honour’ in a lot of things, it seems like an extension of Mari’s version of utopia. He points out the problems, but does believe that change is a natural course of action.

But it doesn’t mean the film is painted with broad strokes. It never shies away from calling out the futilities of caste-based violence, and how, under the right guidance, sports can be a level-playing field where talent is accorded the highest honour. It points out how the differences that can be forgotten on the field don’t really have to creep back once they are out of it. But, in the process, Mari also doesn’t forget to point out that all of this is easier said than done.

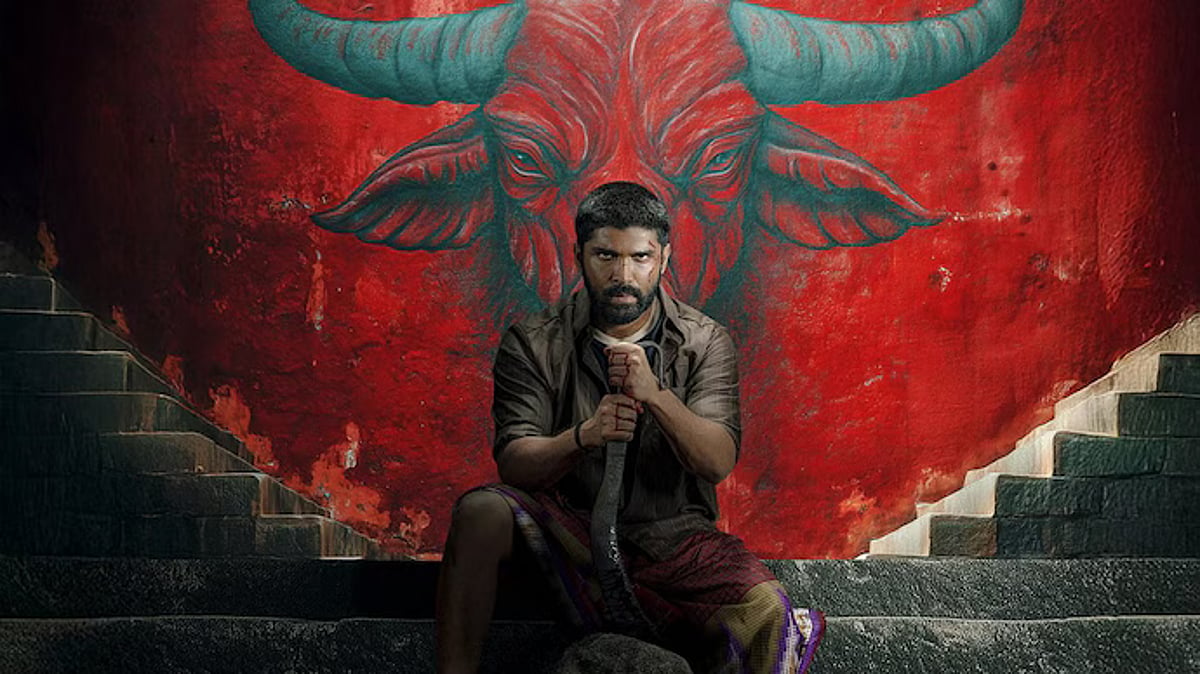

Bison shows how Kittan doesn’t even get the opportunity to think about his passion, his future, his love, his friendships, and his family. He is just reacting to whatever is thrown his way, and the only place where he feels in control is the Kabaddi ground. It is poignant how Kittan has to run his emotions out. However, Dhruv’s rather restrained performance takes some time getting used to because, for a long time, we don’t see him doing much except excelling in the Kabaddi matches, and hitting people who insult his father. There is a sense of repetition here that is frustrating to watch.