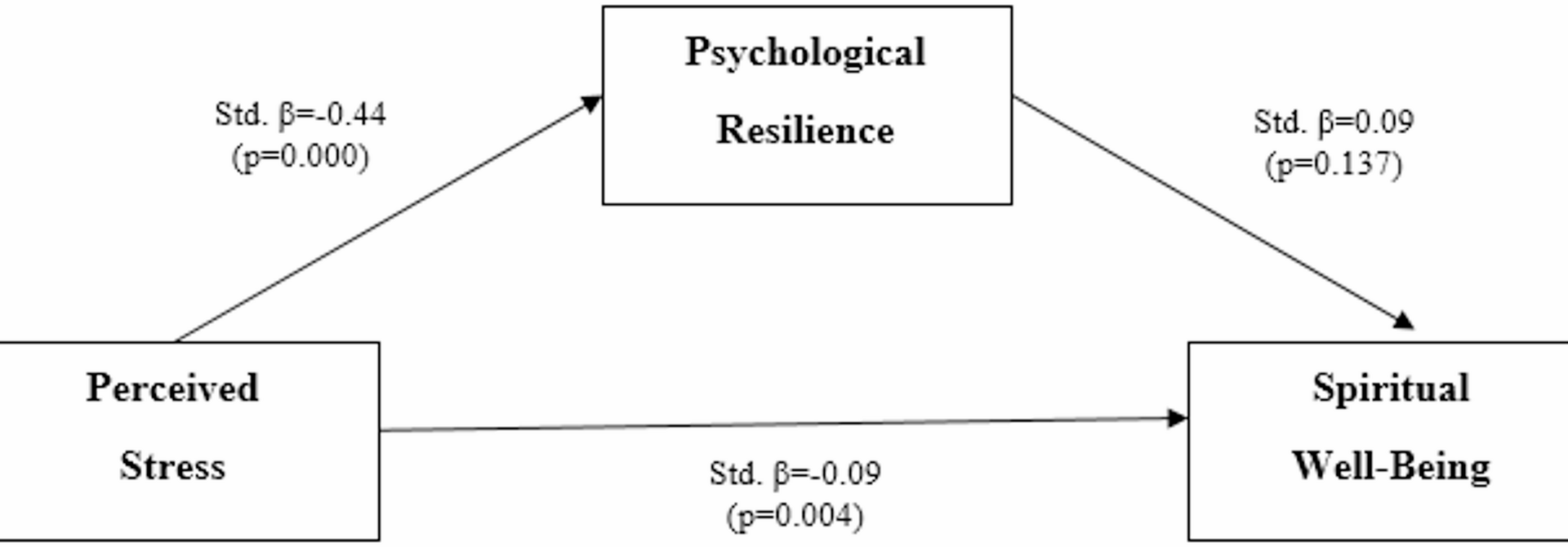

In this study, we found that perceived stress in women had a small but statistically significant direct association on spiritual well-being, whereas psychological resilience not played mediating role in this relationship. This result suggests that higher stress levels were associated with lower levels of women’s spiritual well-being. Although the association size was modest, the finding is consistent with prior research reporting negative associations between stress and various dimensions of psychological and spiritual health [7, 10]. These results highlight that women’s spiritual well-being is not immune to stress; rather, it can be negatively affected when stress levels rise.

The negative association observed between perceived stress and spiritual well-being is consistent with previous studies showing that stress, anxiety, and depression are associated with lower levels of spiritual health [7, 10]. Prior literature has also emphasized that spiritual well-being may promote meaning-making and emotional regulation during adversity [3, 5]. However, in our study, this protective role appeared to be limited, as the association of stress on spiritual well-being remained significant and direct. In terms of mediation, our results diverge from studies reporting that psychological resilience partly explains the association between spirituality and well-being outcomes [6]. Unlike these findings, the current study did not identify resilience as a significant explanatory mechanism.

We also found that more than half of the women in this study (60.8%) had experienced at least one traumatic event in the past. This high prevalence of trauma may help contextualize the direct association observed between perceived stress and spiritual well-being. Traumatic life events may be associated with chronic stress responses and changes in individuals’ cognitive-emotional coping abilities [17]. In this context, the high prevalence of trauma may have intensified the moderate levels of stress observed in our study, emerging as a which may contribute to challenges spiritual balance. The fact that the majority of participants were young women suggests that their life experiences and coping mechanisms may not yet be fully developed, which could further amplify the effects of traumatic experiences and make it more difficult to maintain spiritual well-being.

On the other hand, 54.2% of the women reported that spiritual belief helped them during difficult times. The cultural context of Turkey provides additional insight into these findings. In our sample, 69.5% of women reported praying daily, making it the most common spiritual practice. Prior research has highlighted that prayer, Qur’an recitation, and religious rituals serve as accessible coping strategies for Turkish women facing stressful life events [2, 18]. Such practices may support spiritual well-being by providing meaning, belonging, and hope. Nevertheless, our results suggest that these practices did not completely buffer the negative association with stress. Instead, spiritual well-being appeared lower when stress levels were higher, even within a highly religious and spiritually engaged cultural setting. This finding indicates that spiritual coping (religious/spiritual coping) may have served as a functional strategy for at least half of the participants. Religious/spiritual coping strategies have been reported to be associated with finding meaning in adversity, regulating emotions, and enhancing social and psychological support [19]. One study emphasized that establishing a connection with faith can be effective in reducing stress [20]. Another study found a significant inverse relationship between spiritual health and stress, anxiety, and depression [7]. Recent research strongly supports that positive religious coping fosters post-traumatic growth and psychological well-being, while negative religious coping is associated with increased stress, depression, suicidal ideation, and post-traumatic symptoms [18, 21].

In this study, we found that 69.5% of women reported praying daily, whereas engagement in other practices such as meditation, dhikr (remembrance), visiting places of worship, and seeking spiritual counseling remained considerably lower. The high prevalence of daily prayer (69.5%) reflects Turkey’s religious and cultural context, where Islamic practices are central to daily life. Recent studies in Muslim-majority societies show that religious coping, particularly prayer, can help reduce anxiety and foster well-being by providing meaning, structure, and emotional comfort [18, 22]. However, our findings indicate that while prayer may support spiritual well-being, it does not fully buffer the negative association of stress, suggesting that cultural practices alone cannot eliminate stress-related vulnerabilities. Moreover, traditional gender roles and religious expectations in Turkey may simultaneously heighten women’s stress exposure and reinforce reliance on spiritual practices for coping [22,23,24]. Comparative evidence also suggests that prayer and religious coping strategies play a more prominent role in Muslim-majority contexts than in secular Western societies [18, 25]. These findings underscore the importance of culturally tailored interventions: for instance, incorporating prayer-based or faith-sensitive coping strategies into mental health programs may increase their cultural relevance and effectiveness for Turkish women. A study conducted in rural regions of Western Turkey revealed that while women tend to stay away from mosques, they maintain their religious lives through traditional practices such as prayer at home and shrine visits [8]. This situation highlights the community’s attachment to traditional beliefs and practices and raises questions regarding the impact of modernization on religious life.

Two main factors seem to underlie the high prevalence of prayer. First, in Turkey, prayer represents the most accessible form of both private and domestic religiosity. As a “micro-ritual,” it can be practiced without the need for a special place, equipment, or guidance, providing immediate relief in moments of acute stress. Second, practices like meditation and dhikr require either intensive focus and training (in the case of meditation) or affiliation with and guidance from a specific religious order (in the case of dhikr), which limits participation. These functional and cultural barriers explain the distribution presented in Table 3: while 69.5% of participants reported praying daily, only 8.4% practiced daily meditation.

In our sample, spiritual well-being showed a weak negative association with perceived stress. A connection to an inner spiritual center has been found to be negatively associated with perceived negative stress [26].

In the current study, perceived stress was found to be negatively associated with both psychological resilience and spiritual well-being in women. Bivariate analyses indicated a weak positive association between psychological resilience and spiritual well-being; however, in the path model this link was not statistically significant. The mediation analysis further revealed that psychological resilience was not statistically significantly associated with the relationship between perceived stress and spiritual well-being (β = − 0.005, p =.530). While some studies have suggested that resilience may serve as a mediator in the stress–spirituality relationship [6]. In summary, mediation was tested but not supported. The relationship between perceived stress and spiritual well-being remained direct, and psychological resilience did not demonstrate a statistically significant mediating role. This non-significant result may be explained by characteristics of the sample (predominantly young, highly educated women), the modest reliability of the resilience scale, and the cross-sectional design, which limits causal inferences. Therefore, no buffering or trend effect can be inferred from these findings. Several factors may help explain this discrepancy: the relatively homogenous sample (young, highly educated women), the modest reliability of the Brief Resilience Scale, and the cross-sectional design, which does not allow for causal inferences. Although this suggests that psychological resilience may represent a potential intermediary pathway, our mediation analysis did not statistically confirm this effect, our mediation analysis did not statistically confirm this effect using cross-sectional data. The absence of a significant mediation effect through resilience requires consideration. First, our sample was relatively homogenous, consisting mostly of young and highly educated women, which may have limited variability in resilience levels. Second, although the Brief Resilience Scale demonstrated acceptable internal reliability (α = 0.75), measurement constraints may have reduced the sensitivity to detect indirect effects. Third, the cross-sectional design limits causal inferences; longitudinal or intervention-based studies are better suited to test whether resilience can function as a temporal buffer between stress and spiritual well-being. Therefore, this potential mediating role should be further examined in longitudinal or experimental research designs. Supporting this notion, individuals with higher levels of spiritual intelligence have been found to report lower levels of perceived stress and higher levels of psychological resilience [27].

From the perspective of Turkish women, traditional gender roles and cultural norms place an additional emotional burden on women, thereby increasing their stress levels [28]. Although most participants in our study were young and single, they reported high levels of traumatic experiences and moderate levels of perceived stress. This finding reflects the societal pressures placed on young women and the additional stressors that may hinder effective coping with traumatic events [9, 29].

A strong spiritual framework grounded in traditional and religious values offers notable support in coping with stress, may offer notable support in coping with stress. Among university students who experienced the 2023 Türkiye Earthquake, higher levels of intrinsic spirituality were associated with greater psychological resilience and lower levels of post-traumatic stress [30]. Similarly, during the COVID-19 pandemic, spirituality was found to be positively associated with psychological resilience and negatively associated with hopelessness [28].

Cross-cultural comparisons reveal that spirituality tends to exert more direct protective effects, whereas psychological resilience often functions more indirectly. For instance, in Pakistani youth, spirituality directly buffered the effects of media-induced stress, while resilience provided only an indirect effect [3]. This finding suggests that in some cultures, spirituality is deeply integrated with belief systems and may function independently of psychological resilience.

Another striking finding of the current study was that the association of perceived stress on spiritual well-being was primarily direct, with psychological resilience playing a limited but non-significant role as a mediating variable. Taken together, our findings suggest that stress was directly associated with lower levels of spiritual well-being, while resilience did not show a significant mediating role. In the Turkish cultural context, where daily prayer and traditional spiritual practices are common, such practices may sustain spiritual well-being to some degree, but they do not eliminate the negative impact of stress. There are several potential explanations for this weak and non-significant mediation effect. First, the internal consistency of the Brief Resilience Scale in this sample was acceptable but modest (α = 0.75), which may have limited the precision of measurement and thus attenuated the mediation effect. Second, the sample consisted predominantly of young and single women, which may have restricted the variance in both traumatic experience and psychological resilience, thereby reducing statistical power. Third, given the cross-sectional design of the study, it was not possible to determine causal directionality. Even if psychological resilience might function as a temporal buffer between stress and spiritual well-being, such an effect is difficult to detect using cross-sectional data. Future studies employing longitudinal or experimental designs (e.g., interventions aimed at enhancing resilience) are needed to test the temporal associations and potential causal dynamics thereby increasing the generalizability and explanatory power of the findings.