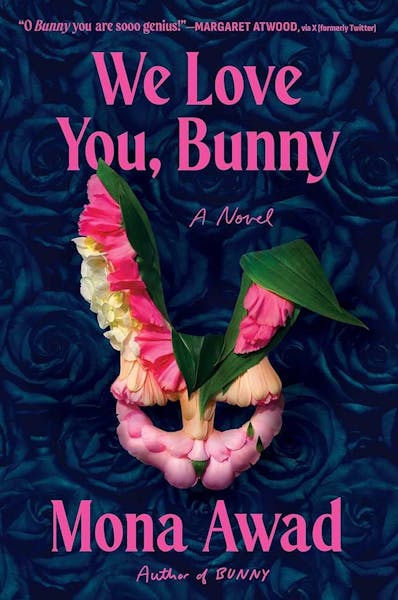

When I first flipped through We Love You, Bunny, the sequel to Bunny by Mona Awad, I tried so desperately to feel the same exhilaration I did when I went through the first book, a charmingly maniacal clash of satire, the pretentiousness of art school and femininity. Instead, I had to read it twice to verify whether my extensive disappointment in it was real.

The sequel takes place after the events of Awad’s Bunny, where Samantha Mackey, a disillusioned writer, struggles through a master’s program in literature with a group of nauseatingly saccharine girls that squeal at lemony cupcakes and rainbows and adoringly term each other the “bunnies.” The plot later bizarrely evolves into them crafting their own ideal versions of a man in a Frankenstein-like manner, but with rabbits. In Awad’s new work, we are left with a retelling of the same story, but instead from the perspective of the clique of bunnies.

However, what I thought made Bunny so gripping was Samantha’s disdainful perspective contrasted against the bunnies’ overdramatic, glittery affection that really underscored the hilarity of their contrived mean-girl-esque personas. But when Awad showcases the bunnies’ perspective on their own, it is painfully obvious how poorly fleshed out each of their characters are, with all of them being virtually indistinguishable. They range from the cheerful murderess obsessed with mini cupcakes, the melancholic murderess obsessed with mini cupcakes and, most importantly, the slightly more cheerful murderess obsessed with mini cupcakes. The tone and writing style retain the same irritatingly faux sweetness, which did wear me out after the first two chapters.

Out of this muddled, hot pink mess, Elsinore emerges as the sole bunny with a somewhat-intriguing character, with her cold demeanor and a mild sprinkling of sibling rivalry trauma separating her from the squealing bunny hive mind. Unfortunately, this is a momentary respite, and she collapses back into her two-dimensional rich-girl mold. Another bunny that marks herself from the rest would be Viktoria. However, it becomes apparent that her apathetic, almost abrasive attitude is a pale imitation of Samantha. Therefore, Awad restricts herself to a strict polarity of female characterization, either overly feminine and fur-loving or indifferent and harshly blunt.

Another facet of Bunny that made it so hauntingly beautiful (which the new novel once more sinks away from) was its bizarre complexity. Awad blurs reality and fiction, with Samantha’s implied mental illness leaving whether or not she actually freakishly experimented on the rabbits to create human flesh with the rest of the bunny clique up to interpretation. It could be a metaphor for the glorification of mental illness in the arts, with the rest of the bunnies trying desperately to recreate the depth of Samantha’s creations that stem from her supposed schizophrenia but ultimately being unable to escape from their wealthy, sheltered lives, as Samantha crafts bunny-humans far more complex than they do.

This is such a prevalent topic, with many believing in mental illness as a force of artistic creation, yet failing to account for the downsides of these conditions that actively impede someone’s life, which negates any positive artistic value. This is cleverly exemplified in the bunnies, who romanticize a very painful condition from their privileged, rose-tinted lenses in an attempt to distinguish themselves as “quirky” and “not like other artists.” However, with We Love You, Bunny, Awad is unable to construct such vivid depth, instead pivoting to the absurd, more literal journey of one of the bunny creations turned human. There is a slight attempt to turn to deeper themes like the impermanence of love and life, but these are glossed over briefly and are not as solidified as in Awad’s previous work.

Her writing style, on the other hand, retains its bitingly sickening hilarity throughout, mocking the frivolous artistic terms like “the body” being hurled around and allowing the bunnies to narrate in first person plural, cleverly articulating their cliquey hive mind. Another redeeming factor of Awad’s writing is her oddly self-aware jabs at the pacing and plot, as a professor calls the bunnies’ experiences “a touch too camp” and “zany,” which does happen to be true. Moreover, her continued onslaught on the despicable nature of patronizing poets in art school and their “overly cadenced” voices remains both wickedly funny and true as it was in the first book.

Awad does claim that this novel works as a standalone book. I would have to disagree wholeheartedly, as it is the literary equivalent of a “this could have been an email” meeting. Perhaps if it was condensed to two chapters at the back of Bunny, I would have been thrilled, but alas, it had to be thinly stretched out as a novel. Awad fails to draw from the intricacy of Bunny but does still maintain her wacky, wildly over-the-top depiction of American art school privilege, which might still make for an entertaining yet mildly frustrating read.

Sanjita Paspulati is a freshman in the College of Architecture, Art and Planning. She can be reached at sp2579@cornell.edu.

Read More