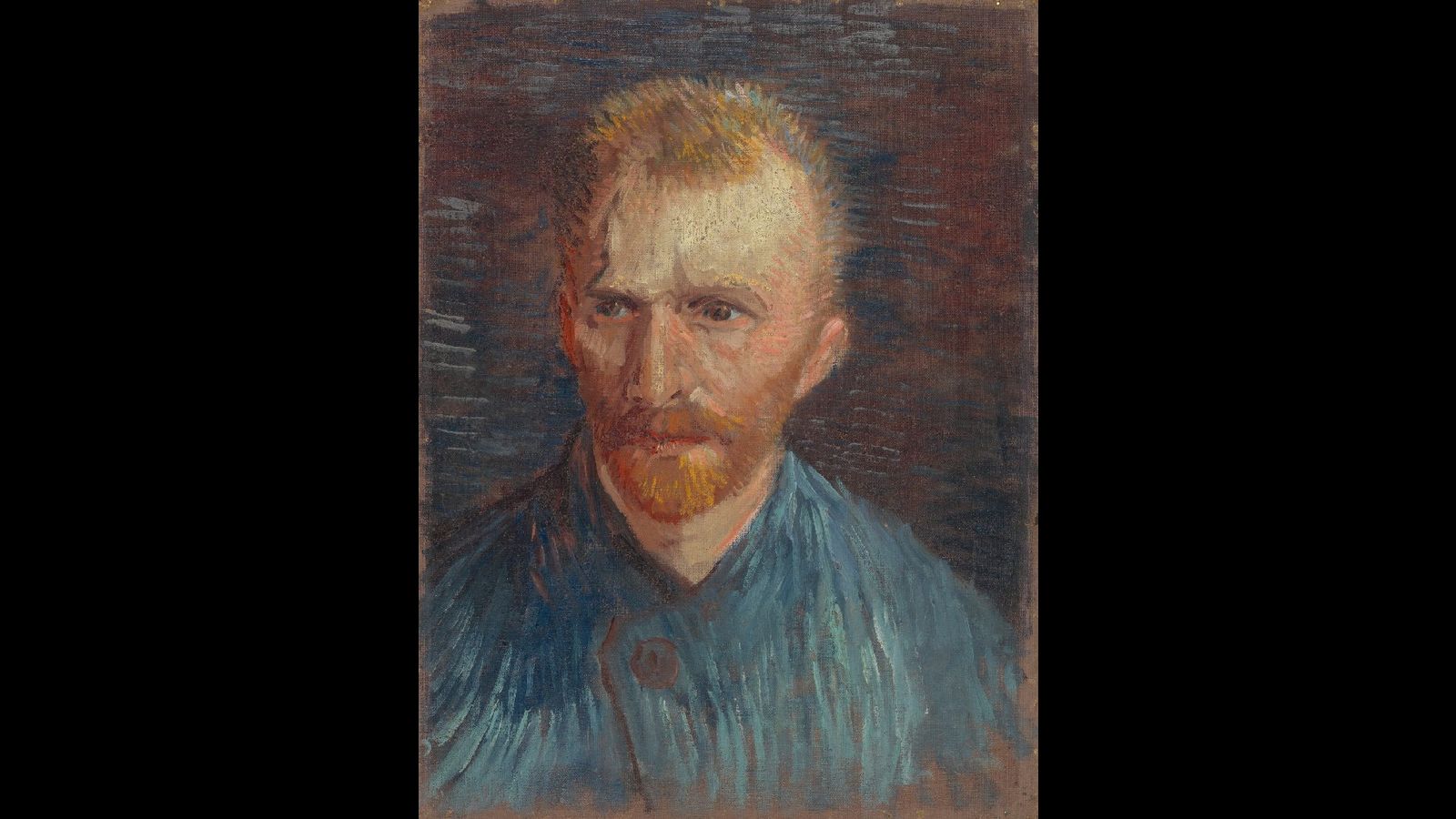

Vincent van Gogh, Self-Portrait, 1887 [Photo by vangoghmuseum.nl]

The future of Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum—home to the world’s most comprehensive collection of works by Dutch master Vincent van Gogh—now hangs precariously in the balance. The Dutch government’s plans to slash annual funding for arts and culture threaten one of humanity’s most vital cultural institutions. At stake is not only the preservation of van Gogh’s masterpieces but the broader principle that art belongs to the public, not to a privileged few.

Next to the Rijksmuseum, the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam is the second most visited museum in the Netherlands and among the most popular in the world. It attracts over 1.7 million visitors annually, reaching a record 2.6 million visits in 2017. For millions, the museum is more than a tourist destination; it is a rare encounter with art that speaks to suffering, empathy and the dignity of ordinary life—a confrontation with the human condition and with nature rendered in trembling lines and blazing colour.

The history of the Van Gogh Museum is inseparable from both tragedy and social aspiration. Vincent van Gogh died at the age of 37 in July 1890, two days after shooting himself in the chest, leaving behind an extraordinary body of work. His artistic legacy passed largely into the hands of his devoted brother, Theo, and later Theo’s son, Vincent Willem van Gogh.

In 1962, Vincent Willem took a decisive step to protect that inheritance from the eyes of private collectors and speculative auction biddings. Recognising the immense cultural value of his uncle’s work, van Gogh’s nephew reached a historic agreement with the Dutch government: the collection—over 200 paintings, 500 drawings, and 800 letters, along with works by contemporaries such as Paul Gauguin—would be transferred to the state under the Vincent van Gogh Foundation. In return for profits made from visitors, the government pledged to build and permanently maintain a museum, ensuring that van Gogh’s work would remain accessible to the public.

The museum opened its doors in 1973, and in the decades since has welcomed nearly 57 million visitors, far exceeding the capacity for which it was designed. After more than fifty years of continuous and intensive use, the building is showing its age. It struggles to meet modern standards of visitor safety and comfort—essential not only for the preservation of fragile masterpieces but also for providing a safe, functional working environment for its staff.

To finance urgent maintenance, climate control upgrades and security improvements, the museum recently requested a modest increase in its annual subsidy—from €8.5 million [$US9.9 million] to €11 million, a rise of just €2.5 million. To put this in perspective, the rise represents barely 0.01 percent of the Netherlands’ total defence spending, or more precisely about 0.00015 percent of the Netherlands’ 1.7 trillion GDP. Allocating €2.5 million would barely register on the national accounts. The Van Gogh Museum laid out a “Masterplan 2028,” a three-year renovation set to begin in 2028, during which the museum further anticipates significant revenue losses due to partial closures.

The Dutch state’s response to the museum’s proposal was both severe and disproportionate. The Ministry of Education, Culture and Science (OCW), under Gouke Moes of the right-wing Farmer–Citizen Movement (BBB)—one of the two remaining coalition partners of the current minority caretaker government—publicly rejected the museum’s appeal, insisting it could “manage” with current funding.

Emilie Gordenker, director of the Van Gogh Museum, explained to the New York Times:

If this situation persists, it will be dangerous for the art and dangerous for our visitors. This is the last thing we want – but if it comes to that, we would have to close the building.

A court case filed by the museum with the state is now set for February 19, 2026, which will determine whether the museum can enforce the 1962 legal agreement. Should the government prevail, it would establish a perilous precedent: priceless works of art could be seized by private collectors, locked away from the public—not because the wealthy “love art” more than workers do, but because they prefer it removed from public life. To deny millions access to beauty, truth, and the memory of human struggle is, in itself, a demonstration of obscene wealth and power.

During its revolutionary ascent in the seventeenth century, the Dutch bourgeoisie played a contradictory yet historically progressive role in the development of art. Emerging from the constraints of feudalism through the Eighty Years’ War of independence against Spain, it shattered the monopoly of aristocratic patronage. For the first time in modern history, artists gained a measure of independence—however limited—from the dictates of both the church and the crown. The painters of the “Dutch Golden Age,” from Rembrandt to Vermeer, reflected this new confidence and curiosity of a society that dared to see the ordinary world through human eyes.

Yet that historical moment, brilliant but brief, has long since passed. In the era of capitalist decline, the same class that once liberated art from feudal fetters has become its greatest oppressor. What was once liberated is now debased and treated as a financial burden—a mirror of a society in decay, led by a rotten and reckless ruling class.

In early 2022, amid a wave of frenzied anti-Russian propaganda, the exhibition “Russian Avant-Garde: Revolution in Art” at the then Hermitage Amsterdam was abruptly cancelled. The works of Kazimir Malevich, Wassily Kandinsky and other avant-garde pioneers were removed in the name of “political virtue.” The decision was lauded overwhelmingly by the Dutch ruling class and the museum’s director, Annabelle Birnie, as a triumph—a so-called gesture of solidarity with the fascist-infested regime in Ukraine.

This episode reflects a far broader political course: the Dutch ruling class, like its counterparts across Europe, North America, and the Pacific, is aggressively pursuing military plans to help redivide the world through imperialist war and genocide, while imposing austerity, nationalism directed against immigrants and authoritarian rule at home.

Vincent van Gogh, First Steps (after Millet), 1890

The COVID-19 pandemic exposed the criminal consequences of governmental neglect and profiteering, which cost millions of lives worldwide. Now, with the war in Ukraine and the genocide in Gaza, the same logic is extended—civilian casualties and human suffering are treated as unavoidable collateral, a necessary “cost” of a global war.

Only weeks before the national elections, the caretaker Dutch government allocated billions of euros for fighter jets, surveillance systems, port expansions and other instruments of death. Alongside this vast rearmament comes a flood of war propaganda, designed to condition the public for new wars.

The figures speak for themselves. Annual defence spending now stands at €25 billion—nearly 10,000 times the modest €2.5 million requested by the Van Gogh Museum for urgent renovations spread over three years. Meanwhile, social programs are being shredded: €1.2 billion cut from education, €2.3 billion from healthcare and €200 million from culture and the arts.

A recent report by the Dutch government’s economic policy agency (CPB) examined the election manifestos of the major political parties contesting the October 29 general elections, spanning the far right to the nominal left. The findings are damning: nearly every party proposes slashing healthcare spending to finance massive increases in defence budgets, placing militarisation above the basic wellbeing of the population.

This continued assault on culture, healthcare, and education is not an isolated Dutch phenomenon; it is part of a broader European and global trend in which the democratic rights and social gains of the working class are subordinated to the profit-driven imperatives of the capitalist system.

The struggle to defend the Van Gogh Museum and to preserve its unique collection cannot be separated from the broader fight of the international working class against genocide, war and the systematic destruction of the living conditions of workers and youth. Culture, education and physical wellbeing are not luxuries to be sacrificed for profit and militarism—they are necessities of life. Art and human progress belong to the people and must be defended as such. After all, history reminds us time and again: “Not by bread alone!”

Sign up for the WSWS email newsletter