Jason Bourne died in the same place he was born — Nixa, Missouri — in an old red-brick orphanage. He was facing down his nemesis, the assassin Paz. Bourne reached for his jacket, and Paz shot him in the heart, only to find that what Bourne had been reaching for was a photograph of his long-deceased lover, Marie. “Why d’you do that?” Paz asked, dropping the photo on to Bourne’s body before walking away.

So read the final pages of Tom Stoppard’s draft of the third Bourne film, The Bourne Ultimatum — commissioned but not used by the film-makers, who opted instead to have Bourne drop into the East River and swim away to fight another day. But when the producer Frank Marshall, the screenwriter George Nolfi and Paul Greengrass met at the director’s home in Henley in the summer of 2008 to discuss how they were going to make a fourth and final film, they quickly arrived at the obvious plot point: Bourne had to die.

“The movie that I wanted to make was the movie where Bourne dies and passes the identity over to a new Jason Bourne,” Greengrass says. “That would have been a really interesting film to have done. He’s going to hand the baton over to the next generation. Do you set that film up as those two fighting, and then finally they realise they’re on the same side? Or does he come in, in a cameo, at the end? Anywhere between those two poles you could have put that film.”

That way, he thought, Universal would have a truly lasting franchise on their hands to rival Bond. That, after all, was why Greengrass had been brought on in the first place. On first reading screenwriter Tony Gilroy’s treatment for the second Bourne film, The Bourne Supremacy, in 2002, “it was like, ‘Oh, I know what they want. They want to take on Bond,’” the director recalls. “It was never said, but that’s what they were hoping for. That played to my competitive nature. I’ve never been crazy about James Bond as a character, whether literary or cinematic. I admire the franchise, of course, but revelling in the cruelty, the amorality, the frankly xenophobic nature of Bond would never have been to my taste.

“But Bourne isn’t about the technology, the Aston Martin and the gadgets and so on. He’s on his own, living by his wits, and when he does have to kill someone he is full of remorse. He’s actually a very moral character. I felt I knew what to do with Bourne, which was to strip him back and make him more iconic — to make him speak less, make him dress only one way, make him enigmatic and engineer a turn from revenge to atonement. And, of course, Bond then copied all that and he started dressing exactly the same — bless him.”

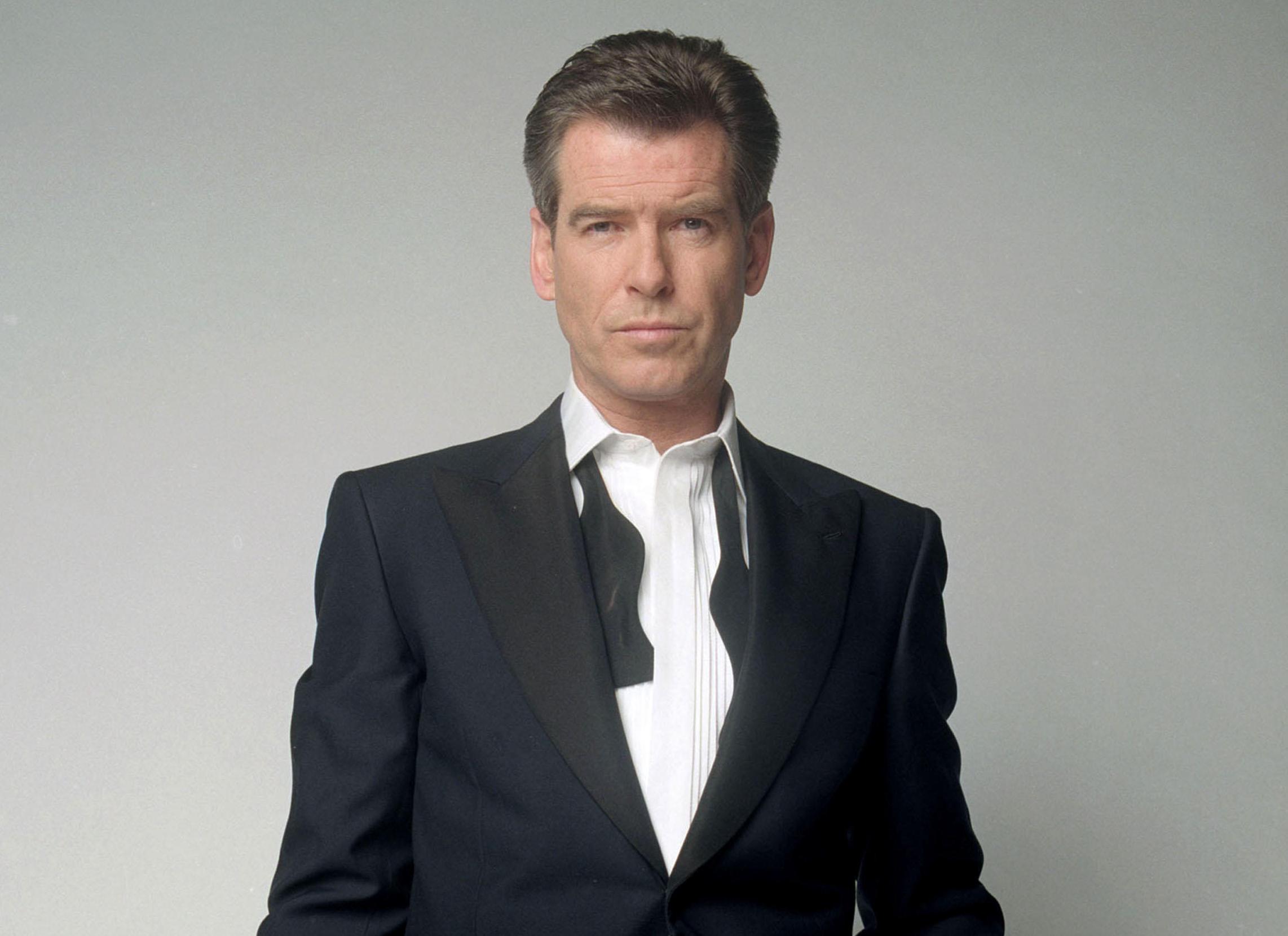

By the early 2000s the Bond franchise was pretty much spent. In Die Another Day (2002), Pierce Brosnan’s Bond, armed with a laser-cutting wristwatch, surfed down the slope of a mountainous CGI tsunami — and everyone shook their heads over the crummy demise of the once-great spy series. Devoid of high-tech gadgets, Bourne had to use only his fists, his feet, and whatever he could grab on the run — a thumb drive, an aerosol can, a walkie-talkie — to outsmart the national defence capabilities of the United States. “Paul Greengrass, who either has very creative attention deficit disorder or the fastest reflexes of anyone over 14, keeps his movie moving and then some,” Manohla Dargis wrote in her glowing review of The Bourne Supremacy in the Los Angeles Times. “Rarely does pop come with such sizzle.”

Pierce Brosnan as James Bond in 2002

ALAMY

Greengrass’s run-and-gun technique — lots of handheld cameras on long lenses, whip-fast editing to give the impression of a live news event — proved wildly influential. Google “shakycam” and hundreds of films come up, from Batman Begins (2005) and Cloverfield (2008) to The Hunger Games (2012), World War Z (2013) and John Wick (2014), as well as Casino Royale (2006) — the first of the Daniel Craig Bonds, which took a leaf or two out of Bourne’s book, not least with the watery death of Eva Green’s Vesper Lynd, echoing that of Marie Kreutz at the start of The Bourne Supremacy. But Bourne had the edge over Bond in one key area, Greengrass tried to explain to the estate of Bourne’s creator Robert Ludlum, as they contemplated a fourth film.

“Unlike James Bond, where you’ve got to recast the character, you’ve actually got a story where the identity is separate from the character,” he told them during a meeting in 2008. “All you need to do for your fourth film is create a character who assumes the identity of Jason Bourne, and David Webb dies either in order to stop him gaining that identity — difficult — or, better still, to ensure that he passes the torch on.”

• Paul Greengrass: ‘Filming fire? I knew it’d be a nightmare’

The problem was the Ludlum estate hated the idea of killing off Matt Damon’s Bourne. After the success of The Bourne Ultimatum in 2007, Universal had signed a deal with the Ludlum estate, engineered by the author’s old accountant, Jeffrey Weiner, ensuring that the estate got contractual approval on screenplays, characters and actors for the new Bourne films and also putting the studio under enormous pressure to make a movie every couple of years or else lose control of the franchise. At the end of January they sent their notes to the film-makers, specifying that “Jason Bourne/David Webb dying at the end of the film is not acceptable to us”.

“They were obsessed with the wider Bourne universe,” Greengrass says. “Characters in the Bourne world whom they could spin off into other movies, instead of concentrating on what made the Bourne franchise unique, which was that it was an unfolding story. That was 100 per cent wrong for Bourne, just as it would have been for Bond — you don’t have Miss Moneypenny movies. They were so fixated on milking the golden cow that they had that they forgot to lay down the plan for tomorrow. It shows you how a great franchise can be f***ed.”

At a meeting on February 12, 2009, Universal’s Donna Langley reiterated to Greengrass that the estate did not want Damon’s Bourne to die on camera or preclude the return of Damon to the franchise. What about if he appeared to die? Marshall, Greengrass and Nolfi all said they knew Damon didn’t want to “appear to die”, as that had happened in the previous two films. The argument continued through September and October, with Langley doing her utmost to see if they could find a way through. One day, while catching the Tube at Oxford Circus, Greengrass saw a poster promoting movie-going that featured Damon’s Bourne, and underneath him the words “I remember everything”.

Greengrass on the set of The Bourne Ultimatum in 2007

ALAMY

“I was feeling pretty anguished about it, and I came around the corner and suddenly there was a big Bourne poster. It was sort of surreal. And I’m looking at this thing, going, ‘He’s remembered everything. It’s over. What are you going to do with another Bourne film?’ That poster made it crystal clear to me. I was, like, ‘This is nuts. If we can’t kill him, I’m not doing it.’”

In early 2010 Greengrass wrote a memo to Marshall, in which he stated: “The only one I’m interested in making — and the only one I can guarantee for 2011 — is the storyline I pitched last year.” The estate refused to budge and Greengrass was forced to walk away. Facing a contractual deadline with the Ludlum estate to produce another film, Universal then turned to Gilroy, giving him the green light for a spin-off script focusing on another black-ops agent, Aaron Cross, but leaving the door open for Damon’s character to return. The Bourne Legacy was released in 2012.

• Paul Greengrass: the Bourne director on making a film about the Utoya massacre

In late 2013 Damon – who made millions from the franchise – met with Greengrass for lunch in LA and tried to persuade him to return to the series. “The truth is, audiences really want another Bourne movie,” Damon said. “Why wouldn’t we give it to them?”

“Well, they might not if we give it to them and it’s bad,” Greengrass replied.

“But that’s not the point. They want it, so why wouldn’t we spend a year or 18 months of our lives trying to give them the best one that we can think of?”

Greengrass wasn’t persuaded, but Damon’s argument stuck with him. “It had a big effect on me,” he says. “You feel a bit of a heel. Loyalty goes two ways. He never said that to me, by the way, but that resonated.”

On set in London with Matt Damon

ALAMY

In early summer 2014, after the editor turned screenwriter Chris Rouse delivered his draft of the screenplay for the fourth proper Bourne film, Jason Bourne, Greengrass “began to feel like I was the only one holding out”, he says. “It’s fomo, is the truth of it. Towards the end I remember it just felt like I was letting the side down at some level. Of course, you’re always going to be paid handsomely and all that — it’s pointless to pretend that’s not part of it. But that’s the only film where that’s been a part of it.’

• Read more film reviews, guides about what to watch and interviews

The deal struck with Universal in September of 2014 was simple: in exchange for agreeing not to kill Bourne, Greengrass could have final cut, with no requirement to embrace Gilroy’s The Bourne Legacy or the wider universe of Aaron Cross, and no interference by the Ludlum estate. “It was a really simple deal,” Greengrass says. “It made the process controllable, which is what I wanted — a more coherent process, where we’ll have a script, rather than being close to the precipice every single day, from the beginning to the day you wrap.”

“But I have to face the fact that perhaps that was also a contributory factor to it not having that sparkle. The anarchy of birthing the previous two was part of why they had this intensity and immediacy, and so Jason Bourne did rather have the feeling of a rock band doing a greatest hits tour. One of the things about film-making that’s a total nightmare is that feeling you sometimes get after you’ve finished a movie, where you go, ‘Well, if I could start all over again, now I know exactly what to do.’ You can be haunted by it. I felt it after Jason Bourne.”

Extracted from The Greengrass Papers by Tom Shone (Faber £30), published on Nov 6. To order a copy go to timesbookshop.co.uk. Free UK standard P&P on orders over £25. Special discount available for Times+ members