Who Benefits is a year-long project tracking and disclosing lobbying and influence, looking now at the environmental lobby group EDS. The project is supported financially by a grant from The Integrity Institute. Newsroom has developed the subject areas, will be led by what we uncover, and retains full editorial control. If you know where influence is being brought to bear, email us in confidence at: trublenzOIA@protonmail.com

The Environmental Defence Society

Part 1 examines a change of fortunes for the EDS, one of the country’s most successful advocacy groups, under this coalition

Part 2 asks how a small team led for decades by one man has achieved outsize influence on our environmental causes and policies

Over the past half century, the Environmental Defence Society has quietly influenced virtually every major piece of environmental law in New Zealand. It has done so without the wide membership of other environmental groups, and without the funding of a major lobbying firm.

The society’s track record has put it at the same tables as Federated Farmers, Infrastructure NZ, Greenpeace, and other groups with reputations and cash flows that dwarf that of the small environmental non-governmental organisation. The scale of its constituents masks the fact that at the end of the day, it’s just a small office under the direction of long-serving chairman and chief executive Gary Taylor.

Former in-house lawyer Kate Storer describes its influence as “so much more than the sum of its parts”. The small team – usually seven full-timers, clustered around a core of two or three – has helped shape the modern Environmental Protection Authority, upended decades of resource management law, and brought precedent-setting litigation before the courts.

It has done so since the time of Robert Muldoon, Prime Minister from 1975 until 1984, under governments of all stripes. It has relied on long relationships with politicians and officials, legal acumen and a reputation as a by-the-book hub of resource management experts; staying out of the spotlight thanks to its small size and aversion to protest.

The society’s core philosophy is to reserve a seat at whatever table the government of the day has to offer.

Now, as the coalition Government continues what Taylor, and others, describe as a “war on nature”, the group’s preferred tactic of negotiation has fallen on deaf ears more often than before. Keys aren’t unlocking the doors they once opened, and some financial taps have been switched off – a colossal challenge for the environmental NGO most reliant on government funding.

One moment captures the essence of what EDS stands for and how it has preserved its influence.

At the group’s 2024 annual conference, a sort of Superbowl for environmental policy, Climate Change Minister Simon Watts was interrupted by protesters from the School Strike 4 Climate.

Watts chose to leave the conference stage without finishing his speech. It was the first and only time a minister has left the stage in such a fashion, and it came at a crucial moment for EDS.

Watts’ Government had just begun a spate of policy changes unlike anything Taylor had seen since Muldoon’s Think Big era: the introduction of the fast-track bill, repealing the oil and gas ban, replacing the Resource Management Act, and scaling back freshwater protections. It had also shut off government funding to environmental NGOs, which some viewed as a dismissal of conservation in general.

It may be surprising, then, that as the dust settled at the Christchurch conference, the first support for Watts came not from his supporters in the crowd but from the leader of the environmental advocacy group whose funding had just been pulled. Taylor even contacted Watts afterwards and apologised.

To anyone familiar with how EDS operates, and how it navigated the 50 years leading up to that moment, this was the only possible course of action.

—

Some of the first advice the group received, back when it was a ragtag assemblage of law students in the 1970s, came from the American biochemist Charles Wurster.

Shortly after the lightning-rod publication of Rachel Carson’s 1962 book Silent Spring, Wurster, founder of the Environmental Defence Foundation – from which the New Zealand EDS took its name – led a campaign to ban the use of the toxin DDT in the United States.

When he visited his protege David Williams in New Zealand around 1972, he found Williams’ nascent spinoff EDS struggling with feelings of litigious imposter syndrome.

Fresh out of law school, this group of 20- and 30-somethings were campaigning against a government in a country with little to no environmental regulations, and Wurster’s advice was simple: “Do it anyway. Just keep suing your government.”

In 1972, Williams lodged a landmark case against the Huntly District Council, which had been dumping raw sewage into the Waikato river. At the time, The Dominion newspaper wrote “it is believed to be the first of its kind relating to the environment brought by a private group”.

The case went all the way to the High Court, with mixed success. The council was found to be breaching the law, paid $250 in legal costs and had to install a treatment plant, but avoided convictions.

Only a few years later, in 1978, the role of full-time coordinator was filled by a young man named Gary Taylor. He was paid $5 an hour.

Taylor would go on to steer the non-profit, and influence environmental legislation, for the next 50 years. His hand remains on the tiller today.

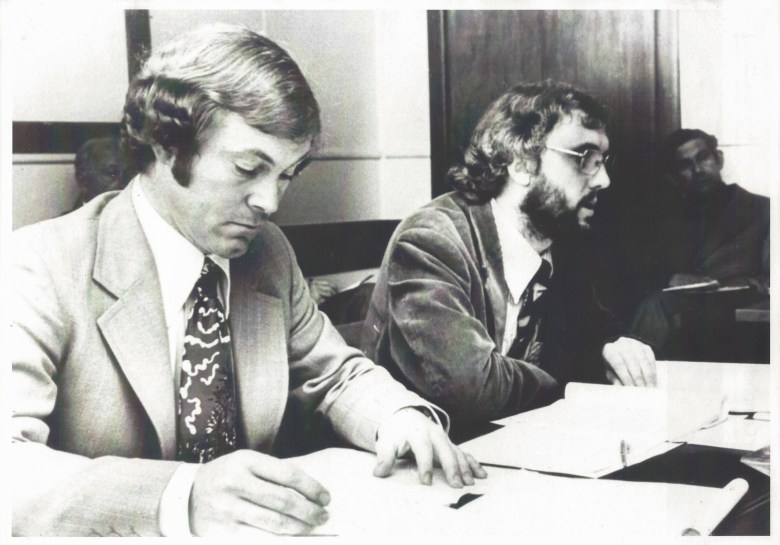

Ian Cowper and Gary Taylor (right) make a submission to the National Development Bill 1979. Their submission led to amendments in the bill allowing challenges to be made to major development projects, like the Aramoana smelter. Photo: EDS

Ian Cowper and Gary Taylor (right) make a submission to the National Development Bill 1979. Their submission led to amendments in the bill allowing challenges to be made to major development projects, like the Aramoana smelter. Photo: EDS

Unlike virtually all the early EDS members, Taylor was not a lawyer. He had a degree in history, which took him into teaching and broadcast journalism: two jobs relying on his ability to communicate clearly, a skill he would lean on during submissions to countless select committees.

During this first chapter of Taylor’s tenure, EDS took several major cases to court. These resulted in modifications to the Huntly power plant, Muldoon’s National Development Bill, and the Mining Act 1971.

Taylor led the group until 1988, when it went into recess. Former EDS board member Mike O’Sullivan, a geothermal expert, said things got harder as private interests and government caught on to the EDS strategy.

In the early days, EDS “was one of the first really effective lobby groups”. In Environmental Defenders, the society’s history book published last year, O’Sullivan described a “golden period of four to five years where companies and government didn’t know what hit them”.

But things got tight as EDS’s competition adapted. Taylor also found himself split between EDS work and local politics, where his usual tactics were proving effective.

In 1986, Metro magazine dubbed Taylor “The Svengali of the West”: a man who rose seemingly from nowhere to occupy a position of considerable influence in the city. He even served a stint as deputy mayor to Tim Shadbolt on the Waitemata City Council.

Two years later, the finances finally caught up with EDS, and Taylor put the group into recess. He focused on politics, and expanded his network across local and national bodies. Then, in 1999, he re-formed the EDS and recruited Raewyn Peart, an expert in environmental and resource management law who, 26 years later, is still at the non-profit.

Starting, or resuming, an NGO is a delicate process; by definition, the not-for-profit structure poses a potential barrier to cashflow. Nearly everyone Newsroom interviewed for this article said this, specifically, meant comparing EDS to, say, the farming lobby, with its private interests and profit motives, was a false dichotomy.

Peart said the motivations for anyone working at EDS were personal, but certainly not in their personal interest. “We could, you know, earn a lot more money working in the private sector,” she said with a laugh.

In 2024, according to annual returns filed to the Charities Service, EDS paid $909,782 in wages across the equivalent of seven full time employees. An even split would see each staff member earning $130,000 annually: twice the median wage, but well below what top-of-the-line resource management lawyers can earn in the private sector.

It has not been a particularly lucrative career for Taylor or Peart, but they have accumulated wealth of a different nature. The time and energy the pair has invested in EDS has paid off in the form of reputation, access to ministers and officials, experience in the courts and the ability to dedicate a career to shaping policy on their own terms, rather than the terms of an employer.

—

In the words of Russel Norman, the former Green Party co-leader and current Greenpeace head in New Zealand, employees at a non-profit like EDS are working for a public good, while the other set “are a bunch of private interest lobbyists who are lobbying just to make money”. “It’s as crude as that.”

Federated Farmers is a non-profit as well, but it works to support its members, who operate for-profit businesses. EDS doesn’t have a member base in the same sense, and works to support aspects of the natural environment. It does not position itself as a sort of foil to Federated Farmers, and has worked with the organisation to produce reports in the past.

Taylor’s strategy, then and now, is to stay at the table. “We prefer to be in the tent. That’s how we’ve achieved anything significant that we’ve achieved, really,” he told Newsroom. But for a group whose staff you could count on two hands, the table was often out of reach.

So, in the early 2000s, EDS figured the best way to guarantee a seat at the table was to host the party itself. The idea of a national conference had been floated around the office for some time, but the financial commitment it represented was a big risk for the recently reborn EDS.

When Taylor secured funding in 2003 to bring an overseas speaker, Peart remembered thinking “cripes, that means we have to run a conference”.

It was a gamble. If people failed to show up, EDS couldn’t absorb the losses. “We would’ve been bankrupt,” Peart said.

But the conference made ripples immediately, and these annual conferences are now a centrepiece of the environmental calendar.

Secretary for the Environment Vicky Robertson, Climate Commission Chair Rod Carr and Auckland City Mayor Phil Goff took the stage at EDS’s 2022 climate change and business conference, one of the group’s signature offerings. Photo: David Hartman

Secretary for the Environment Vicky Robertson, Climate Commission Chair Rod Carr and Auckland City Mayor Phil Goff took the stage at EDS’s 2022 climate change and business conference, one of the group’s signature offerings. Photo: David Hartman

The theme du jour was protecting outstanding natural landscapes. Many attendees represented local government, and in the aftermath of the conference, provisions to strengthen landscape protections were adopted in various district plans.

The then-director of EDS, law professor Barry Barton, said the event shifted the needle on landscape preservation from impossible to possible “quite quickly”, a reckoning for which he gave EDS full credit.

It was not a straightforward process. EDS had a spat with Federated Farmers on Banks Peninsula, and pushback against protections in the Kaipara District resulted in yet another court case, which EDS ultimately won. Landscape protections were strengthened nationally as a result.

Case Study: Kaipara District Council

In 2005, the Kaipara District Council was conducting a comprehensive review of its district plan. It proposed widening landscape protections to 23 newly-identified outstanding natural landscapes.

Landowners, mostly farmers, were opposed to the council exerting control over what they did on their land, and made their opinions heard. At a council meeting in November 2008, the Kaipara District Council voted to take no further action on protecting or identifying outstanding landscapes.

Landscape provisions, previously proposed for the new district plan, were dropped entirely. When presented, the proposed plan still had Chapter 18 reserved for landscape matters, but all that was printed therein was a passage reading “this chapter is intentionally blank”.

In 2009 EDS contested this on the grounds that the Resource Management Act required councils to protect outstanding landscapes, and that omitting the matter entirely was in violation of that requirement.

The council resolved to make amendments by September 2010, but EDS committed to the legal challenge to make sure the council made good on its promise. Both sides readied for court proceedings.

But they never came – Judge Laurie Newhook made his decision on the materials submitted. In what became known as the “blank pages case”, Newhook ruled that councils did have a responsibility to include these provisions, and had to do the work themselves; they couldn’t be left blank in the hopes that a group like EDS or a government agency would step in to fill the gap.

The decision led to landscape protections being included in the 2010 Kaipara District Plan, and alerted other councils to the presence of EDS as it worked to gain momentum after resuming operations.

By the end of the decade, another conference would lead to the formation of the Land and Water Forum. The late Rod Oram, a business journalist and former Newsroom columnist, wrote at the time it would be “extremely challenging” for the forum to work, given the competing interests of those involved.

But it proved effective. The forum presented a suite of 53 policy recommendations to government, which led to the National Policy Statement for Freshwater Management in 2014.

The strategy in those first conferences was simple: get everyone together in one room, talk through the issues and find common solutions. It is the playbook EDS still uses; one that has earned it the trust not just of officials but of workers in myriad industries.

One such worker is commercial fisherman Dave Kellion.

Kellion told Newsroom the trust of NGOs in his sector is “very, very low”. The perception of environmental groups was “they make headlines that make little old ladies bequeath their wealth to them.

“They’re a corporation that needs revenue, and they create it by – I wouldn’t say telling lies, but – sensationalising nonsense.”

Despite these views, Kellion worked with EDS on the Sea Change initiative to reform fishery policy. Funding was procured by EDS, which convinced the Auckland and Waikato Regional Councils to back the initiative.

EDS member Raewyn Peart spent time on commercial fishing vessels as part of the Sea Change initiative, which brought together industry leaders, environmentalists and policy experts. Photo: Raewyn Peart

EDS member Raewyn Peart spent time on commercial fishing vessels as part of the Sea Change initiative, which brought together industry leaders, environmentalists and policy experts. Photo: Raewyn Peart

Peart, of EDS, spent a week on fishing vessels seeing firsthand how the industry operated. Kellion, in turn, got to see how the gears of politics turned and ensure his constituents had a voice.

He didn’t expect the final report’s recommendations to be adopted en masse – and they weren’t – but for this second-generation fisherman on the Hauraki Gulf, this was “the greatest thing that’s ever happened in my life, probably”.

Kellion felt he had found an ally in Peart, and by extension, EDS: one of the “mud-throwing” NGOs. “I got a hell lot of respect for the lady. And as a group, they’re looking to make a better world for us.” (The compliment was not necessarily extended to other NGOs.)

The willingness to walk in Kellion’s gumboots was the kicker. “Raewyn, she gets out there and gets out on the ground and sees things for herself, which is really quite different from most of the NGOs,” he said. “I trust her. So, y’know, what does that say?”

—

The group’s influence hinges on shaping policy and litigation: one prong works internally, to build the law, and the other externally, to enforce it. Both are limited by time and money.

Relationships are crucial for the first approach, as thousands of pages of policy recommendations are useless if they aren’t practical or policymakers aren’t willing to listen.

Former EDS staffer Marie Doole, who researches environmental strategy and regulation, said this is where Taylor shines: he plays the long game, knowing that someone might just be a policy adviser today, but could be a commissioner or minister in a decade’s time. “His ability to manage long-term relationships, and to be the same person in all versions of it, is probably his defining skill,” Doole said.

Litigation judgment is essential for the second approach, as EDS can’t afford to take a shotgun approach to court cases: each has to be targeted and winnable. For this, it has relied on a rolling roster of lawyers, some in-house and many working pro bono.

EDS’ biggest win in the courts was the landmark 2014 case against New Zealand King Salmon, which declined to comment for this story.

Case Study: King Salmon marine farms

In 2011, an amendment to the Resource Management Act prompted NZ King Salmon to apply for nine aquaculture permits in the Marlborough Sounds.

Eight of these were in areas prohibited by the local district plan, but the recent amendment provided a workaround. A board of inquiry appointed by the Minister of Conservation (Kate Wilkinson at the time, under the John Key Government) could permit projects prohibited by district plans on grounds of national significance, which King Salmon hoped it would.

The scope of the issue was too much for EDS to handle in its entirety, so it chose to challenge just two salmon farms before the board of inquiry. The board eventually approved four of the nine farms, including one EDS had contested at Port Gore.

The decision noted granting this permit did not give effect to the Coastal Policy Statement. The board ruled that requiring every policy to be met in full “would otherwise set an impossibly high threshold for any type of activity to occur within the coastal marine area”.

EDS challenged this. Its argument centred on a single line from the Coastal Policy Statement: that decision-makers must “avoid adverse effects of activities” on outstanding natural areas.

The case went all the way to the Supreme Court – the first time the RMA had been considered at that level.

EDS argued that the Coastal Policy Statement said “avoid”, and that the RMA mandated regional plans to “give effect to” the Coastal Policy Statement. The question was what was meant by “avoid”: was it a flat-out no, or could it be outweighed by sufficient benefits?

Anyone paying attention to the case knew the consequences were potentially groundbreaking; previously, an “overall judgement” approach had been applied when making decisions like the one to grant King Salmon’s consents in an outstanding area. If the overarching benefits of the project were deemed important enough, the “avoid” clause could be skirted around.

In its final 2014 decision, the Supreme Court wrote the ruling had the potential to affect nothing short of “all decisions under the RMA”.

By siding with EDS, the court officially replaced the overall judgement approach with a new status quo: environmental bottom lines were real, enforceable, and constant. Hard bottom lines set in regional plans could not be overturned in favour of development, and “avoid” meant avoid.

When the final ruling came, it upended decades of resource management status quo and changed the way New Zealand considered environmental bottom lines. In its final decision, the Supreme Court said the ruling had the potential to affect nothing short of “all decisions under the RMA”.

Buoyed by its success, EDS continued to write policy recommendations and take court cases throughout the 2010s.

As the ‘10s rolled into the ‘20s, EDS raised with the Labour government producing policy advice on resource management reform – what would eventually become the Natural and Built Environments Act and Spatial Planning Act – as well as work on Conservation and Wildlife Act reform.

For RMA reform, EDS relied on in-house expert Greg Severinsen, a former Ministry for the Environment policy analyst. In 2020, a group formed by then-Environment Minister David Parker published the Randerson Report – named after the panel’s chair, Tony Randerson, who led EDS’ failed 1981 case against Goldmines New Zealand – a 531 page document recommending a full repeal of the RMA, and suggested legislation to replace it.

Raewyn Peart took leave from EDS to become one of Randerson’s panel members. The report broadly echoed calls made by EDS years before, alongside the society’s partners in the business world: Infrastructure New Zealand, the Property Council and Business New Zealand, to name a few.

Upon the Randerson report’s release, Severinsen said: “We are very pleased to see that the panel has engaged deeply with the EDS project, and it’s great to see alignment with many of our own findings and recommendations.”

Policy work and conferences are only part of EDS’s operations. Its litigation work represents a significant cost, and for this, donations have always been essential. Peart told Newsroom litigation “is really, really hard to fund” because you can’t get funding from traditional sources. Private donations have to fill the gap.

A salmon farm at Waitātā Reach in the Marlborough Sounds, where EDS won a landmark Supreme Court case against New Zealand King Salmon. Photo: Raewyn Peart

A salmon farm at Waitātā Reach in the Marlborough Sounds, where EDS won a landmark Supreme Court case against New Zealand King Salmon. Photo: Raewyn Peart

Previously, it tapped into the Environmental Legal Assistance Fund – a contestable pool of money, managed by the Ministry for the Environment. But that was canned last year by the coalition Government. Peart said: “We’re only really able to continue our litigation programme on the basis of donations.” For those, Peart says local constituents, those concerned about projects in their back yard, often donate to cover costs.

Federated Farmers board member Mark Hooper told Newsroom the litigious approach is what set EDS apart from other environmental groups. “Unfortunately, most of Federated Farmers’ dealings with the Environmental Defence Society happen in court, and it’s usually because we end up on opposite sides of their legal challenges,” he said.

Hooper said this approach, and the necessity to find local funding to fight in court, was a burden on locals. “The sad fact is these legal challenges by EDS can be hugely expensive for communities, who often have to hire lawyers and fight these cases for years,” Hooper said.

The new Natural Environment Act, set to replace the RMA, would change how, when and who can take environmental decisions to court. Hooper hoped it would take away some opportunities for legal challenges.

Fortunately for Hooper, the current associate minister for agriculture and the environment is former Federated Farmers president Andrew Hoggard, who has repeatedly expressed his goal of reworking the RMA in line with industry recommendations. Hoggard did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

“If we want to successfully move towards a less legalistic environmental management regime, EDS will need to find new ways of working,” Hooper said.

One such case has been steadily burning in the Mackenzie high country for years, and has seen Murray Valentine and his Simons Pass Station face off with EDS and other environmental groups in the courtroom more than Valentine would have liked.

Valentine told Newsroom everyone, himself included, has benefited from the process, but the expensive and time-consuming legal proceedings were a drag. “We could have done that all on our own, just by talking through it together,” he said.

Case Study: Mackenzie District Council

In 2017, Judge Jon Jackson ruled that development restrictions under a controversial Mackenzie District Council plan overruled the pre-approvals granted to Simons Pass Station, a dairy operation run by Murray Valentine.

EDS contested Valentine’s plans to intensify dairy operations through what it called a “potential loophole” But Valentine said he wasn’t exploiting anything: “That’s not saying I’ve used a loophole. That’s [saying] the person drafting the plan got it wrong, and it was the outcome that we were able to develop that they didn’t want.”

The case centred on Mackenzie District Council Plan Change 13, which saw activities previously classed as permitted under the Resource Management Act shift to discretionary or non-complying. This meant farmers would have to seek consents to intensify their operations. The plan change, first notified in 2009, only came into effect on 14 November 2015 after years of legal back-and-forth.

The change meant that a water permit granted before 14 November 2015 for intensification activities could continue as a controlled activity. Anything after that cutoff became discretionary, meaning the council could deny the consent on the grounds of environmental impact.

Simons Pass Station had been granted a consent by the 14th. The consent had been appealed to the Environment Court, and it was ultimately upheld – but not until October 2016. EDS argued that this technically put it on the near side of the cutoff date.

Like with the King Salmon case, the Simons Pass argument hinged on one word: “granted”. The question was if the word “granted” in the district plan meant “granted and commenced” under the Resource Management Act, which would give it immediate effect.

In the end, the High Court ruled the consents granted to Simons Pass Station Ltd. to irrigate 2,500 hectares of native tussock commenced at the time of the October 2016 decision, meaning they now needed consents that the council was unlikely to grant. As a result, the dairy farm chose to intensify operations on a smaller parcel of land.

Valentine’s farm is home to 2,500 dairy cows, negotiated to far below the 15,000 originally planned: a number that would have made it the largest dairy farm in Australasia at the time. Valentine also agreed to give 4,000 of his 9,500 hectares to the Crown for conservation, based on a map drawn by none other than Taylor himself – though Valentine said he improved upon and expanded those areas before submitting it.

Despite years of frustrating court proceedings, and of dealing with protesters and lawyers who couldn’t tell him what a heifer was, Valentine didn’t have anything really negative to say about Taylor or the EDS. In fact, Valentine said he’d had “relatively fruitful discussions” with Taylor, as opposed to the Greenpeace activists who chained themselves to his fences.

As far as EDS’ approach goes, Valentine said it was strictly focused on public policy. “It’s not personal,” he said. Valentine found Taylor “a lot more reasonable” than some of the people behind various environmental crusades. Valentine said he could understand why a truly biting critique of Taylor or the EDS could be hard to find.

Once again, Taylor’s long tenure was a factor of note. Understanding the context of farming in the Mackenzie basin was important to Valentine, who has been there for decades. “There is no one in the Mackenzie District [case] who was there when we started. None of the experts and the legal people who act for EDS – apart from Gary Taylor, who, I must admit, has been there as long as I have.”

But in the aftermath of the 2017 case described above, Valentine said it was hard to call it a “win” for either side.

“If you claim a victory, you have a responsibility,” said Valentine. In his experience, when an environmental group takes an issue to court and finds success, they don’t stay in the area to ensure it’s actually preserved.

Outwash plains on Simons Pass Station, where EDS challenged consents for dairying. Photo: Raewyn Peart

Outwash plains on Simons Pass Station, where EDS challenged consents for dairying. Photo: Raewyn Peart

“They don’t take over and follow up with DoC each six months and say ‘you haven’t done anything, you haven’t put in the rabbit proof fence, you haven’t cleared the wilding trees, you haven’t done the wallabies, you haven’t done the deer, you haven’t cleared the rabbits off. You haven’t done the hieracium, you haven’t done anything. You’ve just left that land and the weeds and pests have overtaken it,” said Valentine.

“So I don’t sort-of class that as a win. I cast that as a loss, because the people who win have a responsibility to continue to enhance and protect the land, as farmers need to do if they ‘win’,” he said.

And at the end of the day, win or no, the process could be hugely expensive. “Certainly the amount of money that is spent on expert evidence produced in all of these hearings – these multiple hearings, the mediation meetings that are had to try to get the parties together, the experts who advise councils, who advise farmers, who advise EDS and Forest & Bird and those guys – if you put all that money from those experts into clearing wilding trees, we probably wouldn’t have a wilding tree problem,” Valentine said.

EDS has contributed to these costs, paid by litigation-related donations, an important but not primary source of funding for the group. Besides income from its conferences and funding for specific projects from a few steady donors like the New Zealand Law Foundation, government funds have provided significant income for EDS.

–

Agencies like the Department of Conservation turned to EDS for in-depth, heavy-lifting analysis of policy proposals like reviews of the Conservation Management Planning System review and the Wildlife Act.

Government money had always been an important source of funding for EDS, more so than for other NGOs. Greenpeace won’t touch government money as a matter of principle, and WWF and Forest & Bird rely more on membership and donations than cash from the Crown.

This is not to say the sums are small. Forest & Bird – which has 43 more full-time staff than EDS – took $1.2m from government sources last year. That’s half of EDS’s entire revenue the same year, and just half a million short of EDS’s total donations and government funding.

This is not to say the sums are small. Forest & Bird – which has 43 more full-time staff than EDS – took $1.2m from government sources last year. That’s half of EDS’ entire revenue the same year, and just half a million short of EDS’ total donations and government funding.

The Ministry for the Environment did not provide a detailed breakdown of where specific grants to EDS were spent, only the annual totals (EDS chief operating officer Shay Schlaepfer said the money would have funded research and reports on RMA, freshwater and conservation reforms). But the Department of Conservation provided a line-by-line summary.

Of the $712,699 the department has paid EDS for policy work since 2015, the two biggest earners were $208,000 for the Restoring Nature: Conservation Reform report, published in August last year, and $135,395 for the Reforming Oceans Management report, published in 2022.

The Department of Conservation has contributed $76,000 in conference sponsorships since 2015. And in the early 2020s, as its policy work expanded, EDS’ annual revenue from the Ministry for the Environment nearly quintupled from $106k in 2020 to $510k last year.

This didn’t last, of course, as the newly-elected coalition Government turned off the tap. Taylor said private donations increased at the same time, providing some relief, but EDS found itself reliant, once more, on donors and conference earnings.

The society’s connections with officials remained strong, and it was busy. But, suddenly, more hinged on relationships than it had in years.

As tensions rose between a government Taylor credited with a “war on nature”, EDS found itself still sitting at the table. Environmental policy was changing too quickly to keep up, and Taylor found his influence strong with officials but weakened with some ministers.

The conferences remained a source of hope, as a place where professionals of all stripes could gather and find practical solutions. A sort of safe space for pragmatic policy work.

Doole, the environmental strategy and regulation researcher, told Newsroom: “It’s really hard in an adverse political context to get a sitting minister to come and speak at a conference, because they tend to close ranks, right? Or speak mostly to favourable crowds. And it’s only really EDS that can get them out into public and ask them questions.”

If all else fails, there’s one advantage of playing a long game. Taylor: “In the end, if no one’s listening, it’s a question of waiting them out.”